The client reports localized deep pain, low down, on the right side of the back that sometimes radiates into the buttocks and posterior of the right thigh. They say that the pain gets worse when standing up from a seated position or when climbing stairs. The therapist asks the client to point to the location of the pain, and the client pushes into the tissue beside the right side of the sacrum.

The massage therapist targets the site of the pain, applying cross-fiber friction to the right sacroiliac ligaments and deep kneading and compression to the gluteal muscles, piriformis, and erector spinae. The massage concludes, the client dresses, and the therapist returns to assess the results of the session. The therapist is puzzled and discouraged when the client points higher up on their low back and says, “Now the pain is here.” when climbing stairs. The therapist asks the client to point to the location of the pain, and the client pushes into the tissue beside the right side of the sacrum.

Add Your Heading Text Here

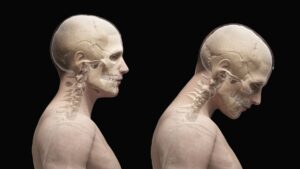

I’ve found this fast-paced spindle stimulating maneuver particularly effective when treating clients with postural ergonomic stress, as seen in Dr. Vladimir Janda’s Upper and Lower Cross Syndromes (Image 1). Janda’s cross syndrome patterns may generally be described as weakening and lengthening of posterior chain muscles, such as the rhomboids, serratus anterior, and gluteals, and tightening and shortening of opposing anterior muscles, such as the pectorals and iliopsoas. Janda’s cross syndromes are not clinically flawless, but they do offer a simplified roadmap to aid us in assessing weak postures that, left untreated, may lead to chronic neck and back pain.

Clients develop these syndromes for many reasons, from prolonged sitting to midbrain hardwiring issues. Even the memory of an injury and the pain associated with it can cause the body to behave as though it was still injured. This locks the client into the very posture that afforded them avoidance at the time. Likewise, those engaged in job-related sustained or repetitive postures develop muscular imbalances seen in clinic every day. Before using Spindle-Stim to address such issues, it helps to understand the neurology of this muscle spindle stimulation technique. From there, you can begin to assess, treat, and reassess to determine if the therapeutic intervention has helped.

I’ve found this fast-paced spindle stimulating maneuver particularly effective when treating clients with postural ergonomic stress, as seen in Dr. Vladimir Janda’s Upper and Lower Cross Syndromes (Image 1). Janda’s cross syndrome patterns may generally be described as weakening and lengthening of posterior chain muscles, such as the rhomboids, serratus anterior, and gluteals, and tightening and shortening of opposing anterior muscles, such as the pectorals and iliopsoas. Janda’s cross syndromes are not clinically flawless, but they do offer a simplified roadmap to aid us in assessing weak postures that, left untreated, may lead to chronic neck and back pain.

Clients develop these syndromes for many reasons, from prolonged sitting to midbrain hardwiring issues. Even the memory of an injury and the pain associated with it can cause the body to behave as though it was still injured. This locks the client into the very posture that afforded them avoidance at the time. Likewise, those engaged in job-related sustained or repetitive postures develop muscular imbalances seen in clinic every day. Before using Spindle-Stim to address such issues, it helps to understand the neurology of this muscle spindle stimulation technique. From there, you can begin to assess, treat, and reassess to determine if the therapeutic intervention has helped.

I’ve found this fast-paced spindle stimulating maneuver particularly effective when treating clients with postural ergonomic stress, as seen in Dr. Vladimir Janda’s Upper and Lower Cross Syndromes (Image 1). Janda’s cross syndrome patterns may generally be described as weakening and lengthening of posterior chain muscles, such as the rhomboids, serratus anterior, and gluteals, and tightening and shortening of opposing anterior muscles, such as the pectorals and iliopsoas. Janda’s cross syndromes are not clinically flawless, but they do offer a simplified roadmap to aid us in assessing weak postures that, left untreated, may lead to chronic neck and back pain.

Clients develop these syndromes for many reasons, from prolonged sitting to midbrain hardwiring issues. Even the memory of an injury and the pain associated with it can cause the body to behave as though it was still injured. This locks the client into the very posture that afforded them avoidance at the time. Likewise, those engaged in job-related sustained or repetitive postures develop muscular imbalances seen in clinic every day. Before using Spindle-Stim to address such issues, it helps to understand the neurology of this muscle spindle stimulation technique. From there, you can begin to assess, treat, and reassess to determine if the therapeutic intervention has helped.

Muscle spindles and the stretch reflex

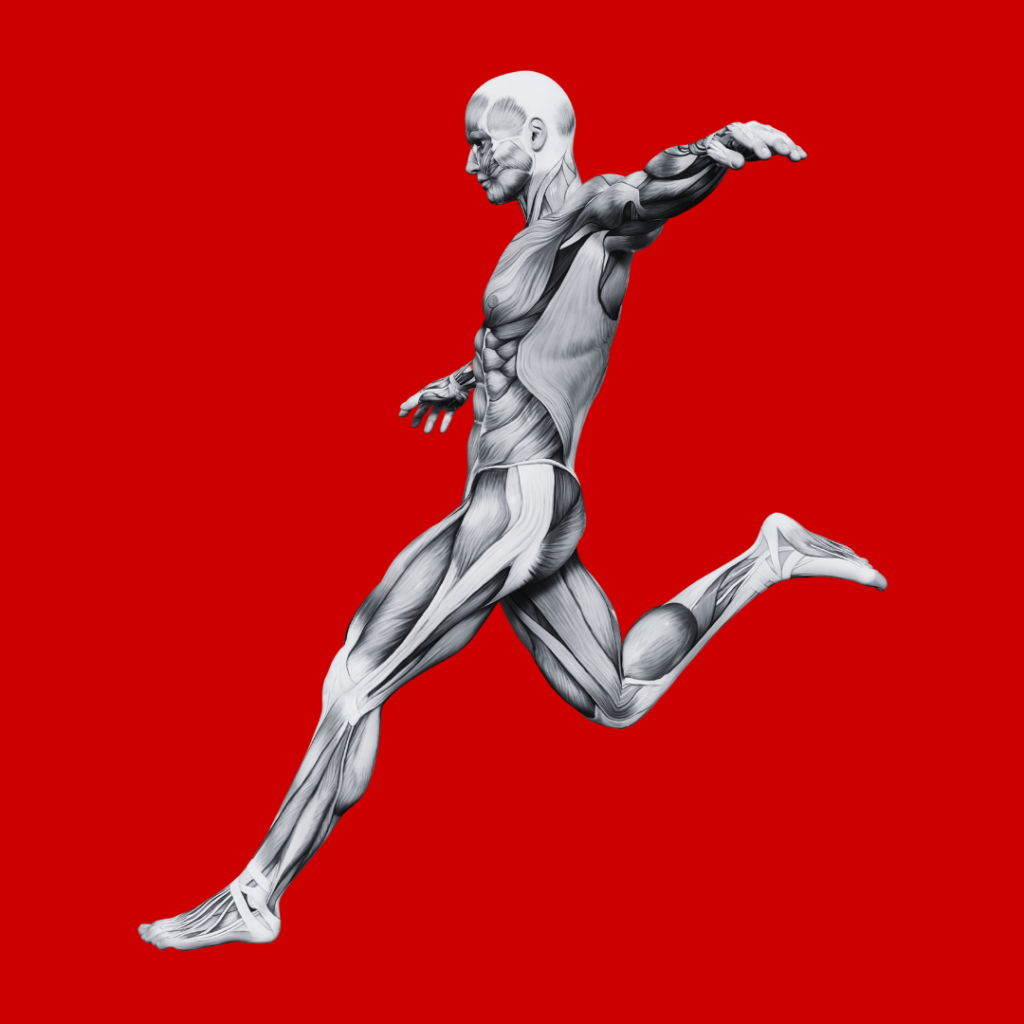

For the assessment, I typically begin by asking the client to perform specific active movement tests, making note of any range of motion restrictions (Images 3.a and 4.a). Testing side-to-side, if I discover a muscle group that appears to have a weak firing pattern, I log the information in my SOAP notes, treat the area, then reassess. The treatment itself focuses on using soft fingers, fists, or forearms to create a rapid length change in the agonist muscle’s extrafusal fibers (Images 3.b and 4.b). This, in turn, stimulates intense firing of the intrafusal fibers, which are valiantly trying to maintain a constant length-tension relationship with the muscle being stretched.

I’ve found this fast-paced spindle stimulating maneuver particularly effective when treating clients with postural ergonomic stress, as seen in Dr. Vladimir Janda’s Upper and Lower Cross Syndromes (Image 1). Janda’s cross syndrome patterns may generally be described as weakening and lengthening of posterior chain muscles, such as the rhomboids, serratus anterior, and gluteals, and tightening and shortening of opposing anterior muscles, such as the pectorals and iliopsoas. Janda’s cross syndromes are not clinically flawless, but they do offer a simplified roadmap to aid us in assessing weak postures that, left untreated, may lead to chronic neck and back pain.

Clients develop these syndromes for many reasons, from prolonged sitting to midbrain hardwiring issues. Even the memory of an injury and the pain associated with it can cause the body to behave as though it was still injured. This locks the client into the very posture that afforded them avoidance at the time. Likewise, those engaged in job-related sustained or repetitive postures develop muscular imbalances seen in clinic every day. Before using Spindle-Stim to address such issues, it helps to understand the neurology of this muscle spindle stimulation technique. From there, you can begin to assess, treat, and reassess to determine if the therapeutic intervention has helped.

Summary

By moving in all directions across the muscle belly, the Spindle-Stim maneuver triggers a mild stretch reflex that helps protect the muscle from injury. I’ve found that stimulating this stretch reflex not only aids in strengthening the weak agonist muscles by restoring resting tone, but also facilitates improved communication between the inhibited muscle and the client’s nervous system. In the beginning, this fast stretch produces a relatively short-lived contraction of the agonist muscle and inhibition of the antagonist muscle. However, over a series of sessions, these effects appear to last longer, particularly when clustered with graded exposure stretching techniques and specific home retraining advice.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Dalton Technique Tour course!

NEW! USB enhanced video format

Discover deep tissue, pin and stretch, nerve mobilization, and graded exposure stretches in this comprehensive “technique only” program. Upon completion, you will receive 16CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office. Save 25% this week only. Offer expires Monday, January 19th. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course.

BONUS: Order the home study version and get access to the eCourse for free!