A case of mistaken identity!

A 44-year-old orthopedist, who we’ll call Dr. Smith, was referred to me complaining of eight months of debilitating, self-diagnosed, IT-band friction pain. During his history intake, he admitted suffering sporadic foot, hip and low back soreness but dismissed these issues as “unrelated.” A self-described “weekend-warrior,” Dr. Smith’s knee pain flared with excessive running or cycling. Both he and his staff (a physical therapist and physiatrist) had carefully scrutinized the painful knee and arrived at a unanimous diagnosis of iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome based on results from Ober’s Test (determines the tightness of the ITB), Renne’s test (specifies the area of pain during weight bearing) and Noble’s test (identifies the area of pain when the leg is flexed at a certain angle). To further strengthen their diagnosis, MRI studies showed a thickened iliotibial band over the lateral femoral epicondyle. The summation: diagnosis confirmed as IT-Band Friction Syndrome. Case closed.

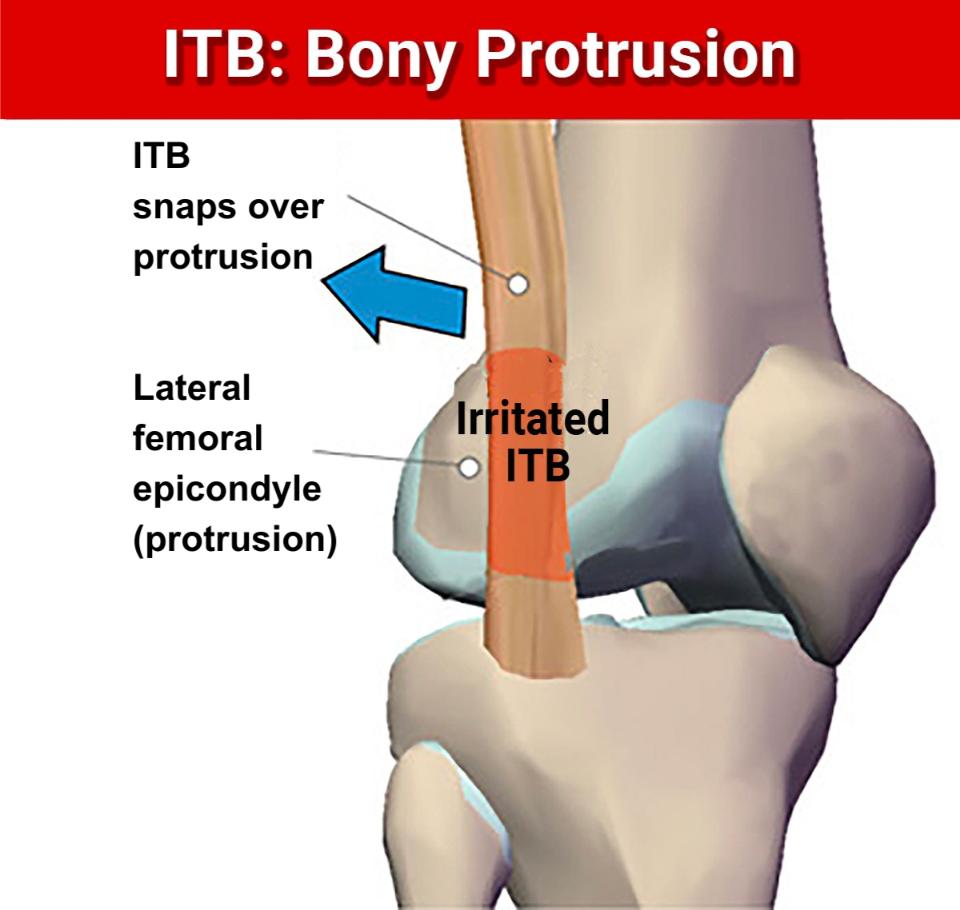

Dr. Smith related that his group’s initial treatment goals focused on relieving the (supposed) inflammation via ice treatments and anti-inflammatory medications followed by a series of physical therapy sessions. Sadly, the “series” of physical therapy slowly evolved into months of heartbreaking disappointment. Typical treatment modalities (stretching, ultrasound, electrical stim, cross-fiber frictioning and trigger point work) brought little relief. Discouraged with the lack of progress, Dr. Smith and his physiatrist partner began a more aggressive approach with corticosteroid and proliferation injections (Image 1. ).

Although many of their ITB patients responded favorably to this treatment protocol, Dr. Smith did not. Desperate to get back to his biking and running regime, Smith decided to undergo a surgical release of the ITB at the posterior 2 cm where it passes over the lateral epicondyle, but still no relief. So how did eight months of aggressive treatment lead to abysmal failure?

IT-Band friction is generally thought to be a multi-factorial, non-traumatic, overuse condition in which the distal aspect of the iliotibial band rubs over the lateral femoral epicondyle during repetitive knee flexion and extension movements (Image 2. ). This ultimately leads to irritation of the iliotibial band, bursa and lateral synovial recess. In this popular theoretical model, the deep posterior ITB fibers are more vulnerable to back-and-forth rubbing on the knee’s epicondyle. Several studies have described a dynamic “impingement zone” at approximately 30 degrees of knee flexion where the ITB is subject to microfiber tearing and associated inflammation.

Therapists who abide by this “conventional wisdom” often seek out the sore spots around the condyle and cross-fiber friction the affected tissue in an effort to break down weak-linked adhesions, enhance fibroblastic activity and encourage tissue remodeling.4 Some focus on relaxing the IT-band by easing tension in the tensor fascia lata muscle. Both these approaches may be effective, but only if the condition is correctly assessed as IT-band friction syndrome.

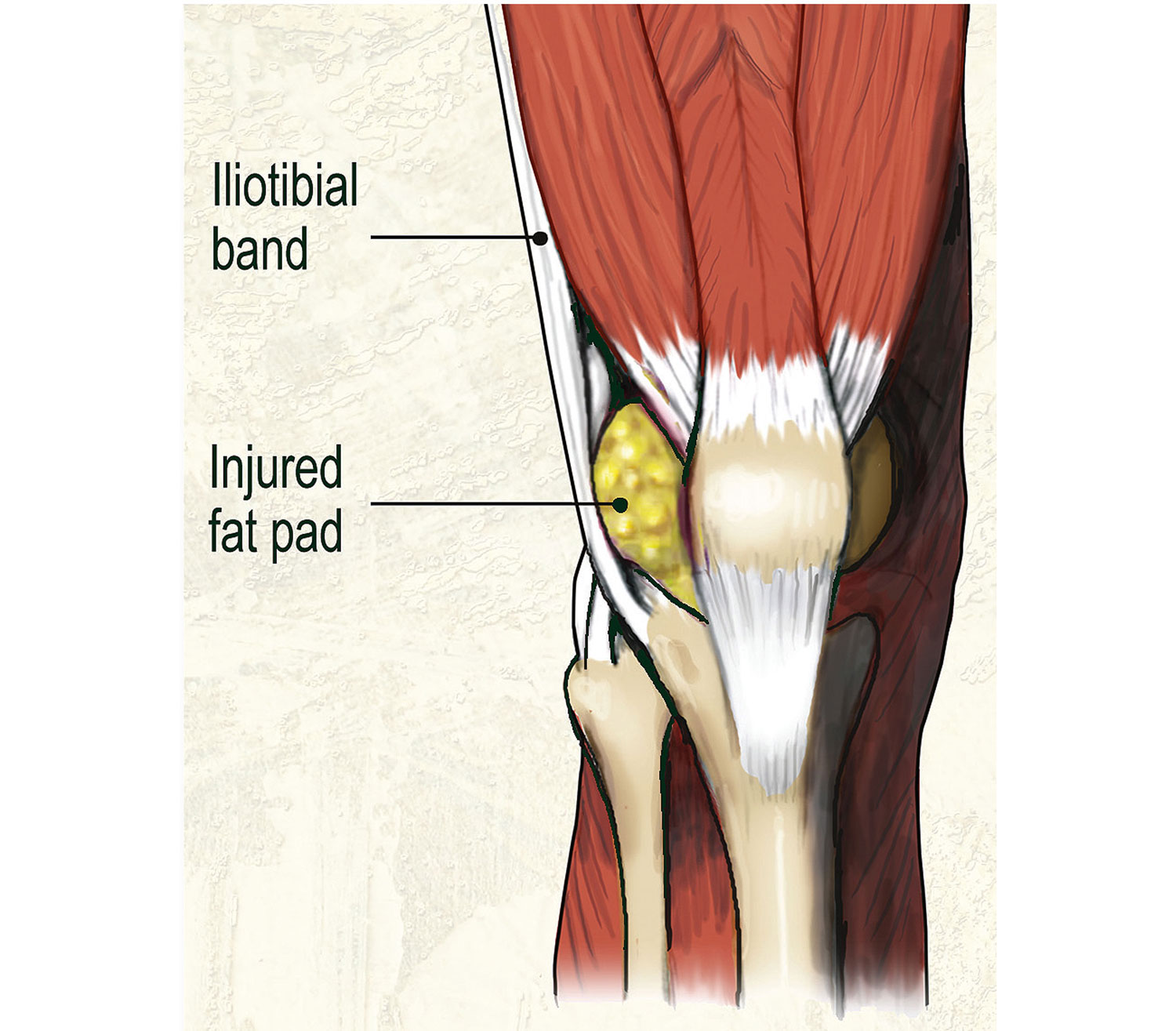

In a compelling paper published in the Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, a prestigious research team led by John Fairclough and seven co-authors challenged the idea that excessive friction between the ITB and the lateral femoral epicondyle creates microscopic tears and “inflames” the tract or a bursa.5 These researchers found that several basic anatomical ITB principles had been overlooked: (1) The ITB is not a discrete structure but a thickened part of the fascia lata which envelops the entire thigh; (2) It is connected to the linea aspera by an intermuscular septum and to the supracondylar region of the femur (including the epicondyle) by coarse, fibrous bands which are not pathological adhesions; and (3) A bursa is rarely present but can be mistaken for the lateral recess of the knee.

According to their findings, it appears the ITB is actually prevented from rolling over the epicondyle, partly because of its femoral anchorage and partly because its fibers are bound tightly to the tough enveloping fascia lata.

Although Fairclough and his team were able to induce slight medial-lateral movement across the condyle, they proposed that ITB pain was primarily caused by increased compression of a highly vascularized and innervated layer of fat and loose connective tissue separating the ITB from the epicondyle (Image 3. ). Dr. John Fairclough concludes that “ITB syndrome is related to impaired function of hip and leg musculature and its resolution can only be achieved through proper restoration of lower quadrant muscle balance.”

One of the first things that caught my attention while observing Dr. Smith’s gait was the presence of a cavus right foot (high rigid arch) presenting on the same side as his ITB pain. As he walked down my hallway, it was obvious the stiff supinated foot was preventing internal tibial rotation during heel strike. This seemed rather unusual since friction or compression of the ITB is generally thought to result from foot hyperpronation coupled with excessive internal tibial rotation.

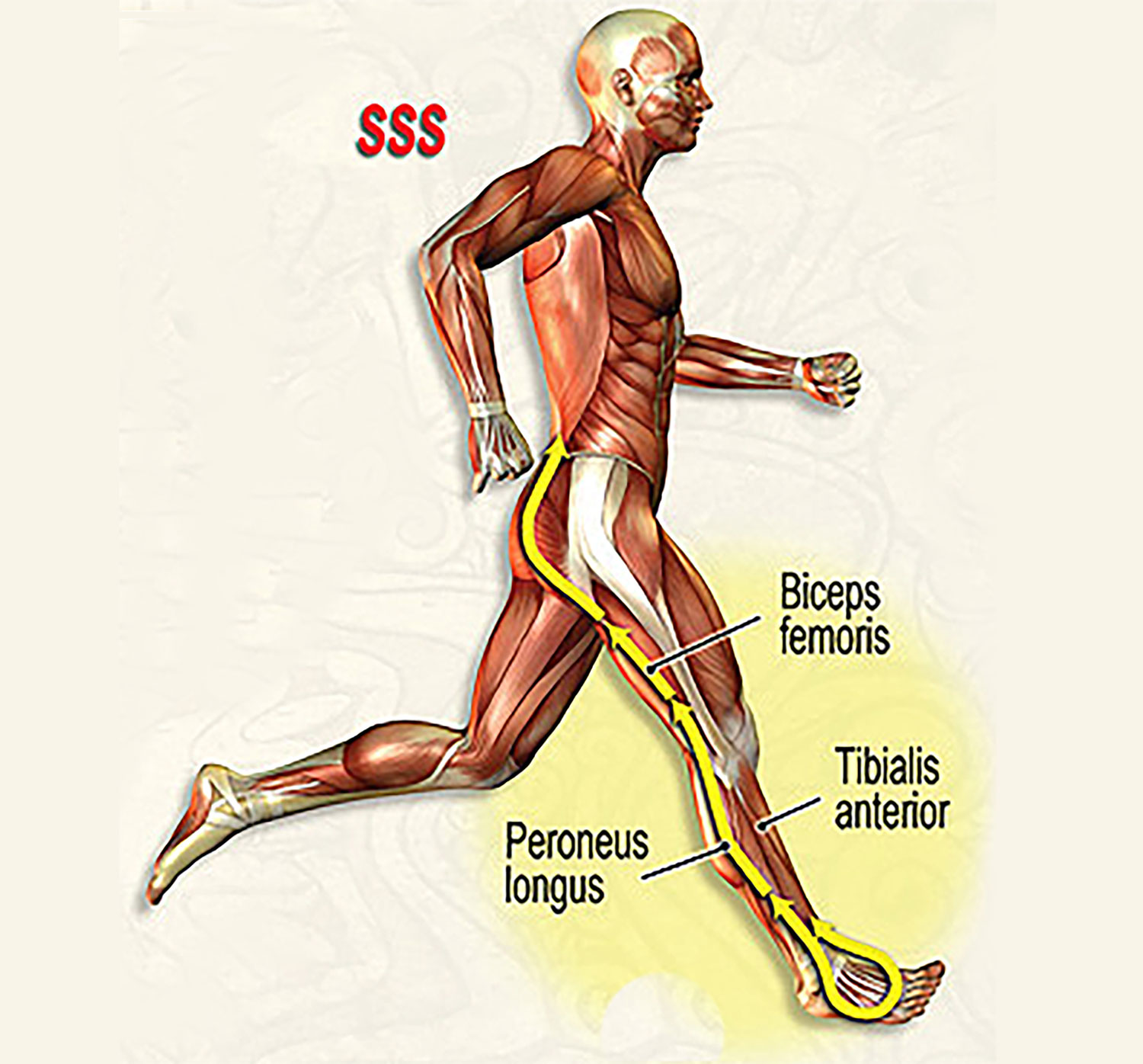

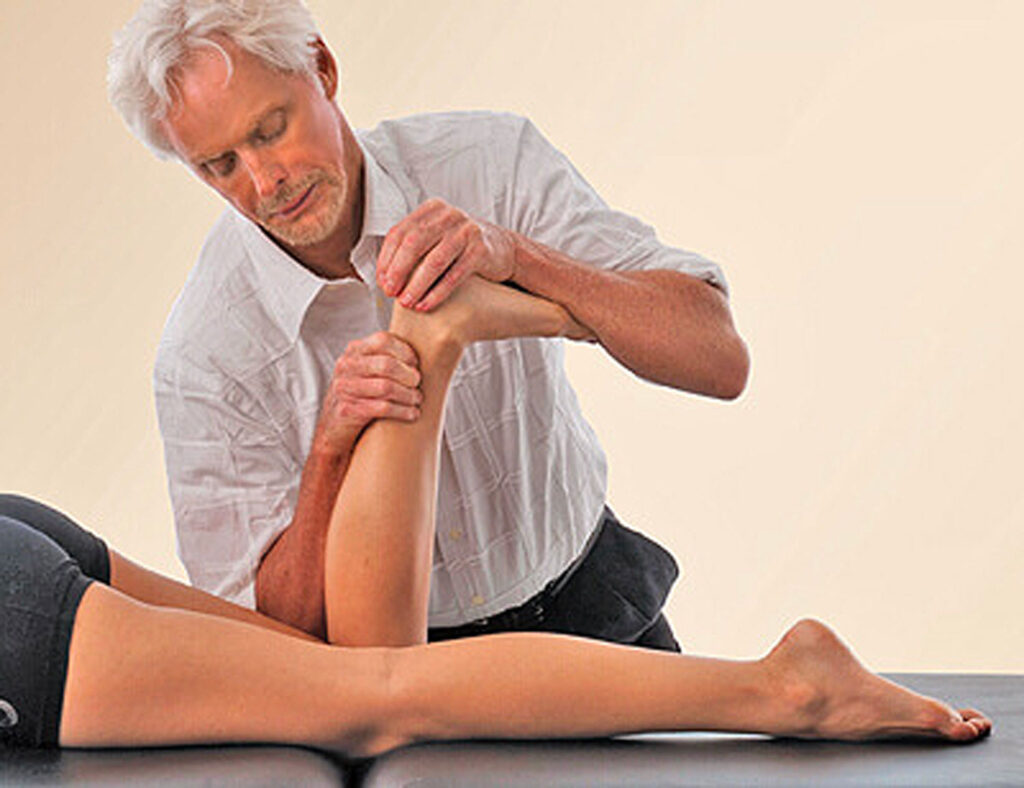

Although gait observations, anatomical landmark assessments, and functional testing revealed myoskeletal imbalances through the hips and lumbar spine, I initially decided to address the cavus foot problem. (See before-and-after pics Image 4. ) My experience has shown that a rigid cavus foot stresses all myoskeletal structures (foot to lumbar spine) leading to disorders such as peroneus tendinosis, stress fractures, trochanteric bursitis, plantar fasciitis, tibiofibular fixations, and hip/back pain, but not IT-band friction syndrome.

I find this often neglected tib/fib joint to be the “key lesion” in many lower extremity disorders. Optimal “stirrup spring system” functioning demands that both ends of the tibia and fibula (proximal and distal) maintain smooth cephalad and caudal movements (Image 5.). If working properly, the tib/fib articulations should perform as magnificent shock absorbers with their actions enhanced by tibialis anterior and peroneus longus and kept in sync by a resilient but tough interosseous membrane.

Some cavus feet (particularly those with claw toes) do not respond well to manual therapy. Fortunately, Dr. Smith’s foot did regain flexibility as the muscles of the lateral fascial compartment were separated. Once myofascial flexibility improved, rear and forefoot joint mobilization routines helped restore glide to the rigid tarsal bones (navicular, cuboid, and cuneiforms) and the talocalcaneal joint. Although this myofascial/joint mob protocol flattened some of the concavity in his arch, it quickly became apparent that most of Dr. Smith’s foot rigidity was coming from a severely fixated tibiofibular (ankle) joint.

The “Figure 8” plantar and dorsi flexion technique shown in Image 6. was successful in loosening fibrotic ankle ligaments and articular cartilages which improved anterior/posterior and superior/inferior glide, but the distal fibular shaft was resistant. Searching for the restriction, I moved up to the proximal fibular head and tested for A/P glide there. Bingo! Finally, the “main event” likely responsible for months of mysterious lateral knee pain Dr. Smith had been experiencing was exposed.

With the knee flexed, my fingers and thumb were unable to budge the fibula in an anterior direction and any attempt to pressure it back into place replicated the intense pain Dr. Smith identified as the source of his problem.

Runners like Dr. Smith share a high risk for hamstring injuries with the most commonly torn of the group the biceps femoris. When asked about past hamstring problems, Smith related that he had suffered a chronic pull a year before the knee began to flare. Therefore, with each step, the injury-shortened biceps femoris tugged on the fibular head causing chronic repetitive microtrauma at the tib/fib articulation.

In time, the fibula became posteriorly fixated on the tibia causing joint play loss and lateral knee pain. By applying a simple contract/relax technique, we were finally able to establish normal movement to the fixated tib/fib articulation thereby resolving his painful condition. (Image 7. )

As with many conventional protocols, stepping outside the box provided that important distinction to Dr. Smith’s recovery – relying more on accurate identification and restoration of the functional biomechanical deficits in the entire kinetic chain rather than focusing on a specific injured tissue. Incorporating myofascial and skeletal mobilizations to Dr. Smith’s foot, ankle, proximal fibular head, hip, and pelvis proved the “key” factors allowing him to return to normal running and biking activities.

References

- Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, et al. Is iliotibial band syndrome really a friction syndrome?Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, April 2007;10(2):74-6.

- Orchard JW, Fricker PA, Abud AT, et al. Biomechanics of iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. American Journal of Sports Med, 1996;24:375-9.

- Hamill J, Miller R, Noehren B, Davis I. A prospective study of iliotibial band strain in runners. Clinical Biomechanics, 2008;23:1018-25.

- Clement DB, Taunton JE, Smart GW, et al. A survey of overuse running injuries. Physical Sports Medicine, 1981;9:47-58.

- Schwellnus M, Mackintosh L, Mee J. Deep transverse frictions in the treatment of iliotibial band friction syndrome in athletes: a clinical trial. Physiotherapy, 1992;78(8):564-9.

- Ellis R, Hing W, Reid D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome – a systematic review.Manual Therapy, 2007;12:200-8.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.