The temporomandibular joint, or TMJ, is one of the most complex and important joints in the human body. It functions like a sliding hinge, connecting the mandible to the temporal bone of the skull, and is supported by an intricate web of muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues. Muscles such as the masseter, temporalis, pterygoids, hyoid stabilizers, and suboccipitals all play a role in its function. Because the TMJ is intimately linked to both the cervical spine and cranial structures, dysfunction here can extend far beyond the jaw, often creating a chain reaction of pain and compensation throughout the body.

TMJ dysfunction can arise from many different causes. Blunt trauma to the head or neck, whiplash injuries, or even a slip-and-fall on the sacrum may disturb spinal alignment in ways that ripple upward into the cranial bones and jaw. Orthodontic interventions sometimes contribute as well, altering bite mechanics and mandibular positioning. More commonly, modern lifestyles set the stage. Prolonged deskwork and “text-neck” postures push the head forward in the sagittal plane, placing constant strain on both the cervical spine and the TMJ (Figure 1). For massage and bodywork practitioners, appreciating how these structural relationships play out is essential in supporting clients with TMJ pain.

According to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, TMJ dysfunction may contribute to symptoms far beyond jaw clicking or discomfort. Clients often complain of headaches, fatigue, poor sleep, irritability, ringing in the ears, sinus congestion, or even recurring ear infections. Others report difficulty concentrating, head and neck tension, or widespread pain patterns that make TMJ dysfunction feel like more than a local joint issue.

Forward head posture plays a particularly important role in this condition. When the head shifts forward, the body instinctively relies on a proprioceptive reflex known as the Law of Righting. In order to keep the eyes level with the horizon, the occiput tips backward on the atlas. This adjustment may stabilize vision, but it comes at the expense of the neck, which is forced into sustained isometric contraction in the suboccipitals and other cervical extensors. Over time, this pattern places the entire nervous system in a heightened state of alert.

As the head juts forward, passive tension also builds in the hyoid and digastric muscles. The brain, in effect, recruits the jaw to help pull the cranium back into position. Unfortunately, the hyoid, digastric, and lateral pterygoid are all jaw openers. Sustained contraction in these muscles creates greater stress on the TMJ as the mandible is pulled backward and downward, a displacement known as jaw retrusion. In order to keep the mouth from hanging open, the brain calls on the powerful jaw closers: the temporalis, masseter, and medial pterygoid (Figure 2). What follows is a tug-of-war. Jaw openers and closers contract simultaneously in an antagonistic battle that keeps the mouth closed, but at a terrible cost. The joint surfaces become compressed, nerves irritated, and ligaments strained, setting the stage for the painful TMJ disorders that so often appear in massage and bodywork practice.

Symptoms in these clients may be varied. Pain in the suboccipitals is common, and many report jaw clenching, difficulty swallowing, or even mouth breathing and sleep apnea. Cranial nerve disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia or Bell’s palsy sometimes accompany TMJ dysfunction, as do migraines and general face, head, and neck pain. In long-term cases, irritation may extend to the eleventh cranial nerve, the spinal accessory. Because this nerve innervates the sternocleidomastoid and upper trapezius, chronic irritation can neurologically shorten these muscles, locking the client into a “catch-22” cycle. The SCM pulls the head forward, the upper traps pull it back, and all the while the hyoid, digastric, masseter, pterygoid, and temporalis remain in hypertonic contraction, adding still more compression at the TMJ.

For optimal function, the TMJ surfaces must be able to glide freely on one another. Massage therapy can help by addressing forward head posture first and then working with the jaw directly. Figure 3 shows a technique applied to the masseter, where gentle pressure is used to elicit the Golgi tendon organ reflex and create length through stretch. This decompressive approach, combined with other TMJ and neck techniques, can restore balance to overworked tissues and reduce strain on the joint. Before using any intra-oral techniques, practitioners should always confirm they are within scope of practice in their state.

TMJ dysfunction is rarely just a problem with the jaw. It reflects the ongoing relationship between posture, muscular coordination, and joint mechanics. When massage therapists address head-forward posture, release hypertonic jaw and neck muscles, and support nervous system regulation, they offer clients meaningful relief from a condition that can otherwise become a frustrating and debilitating cycle.

References

- Cullen, KE. (Mar 2012). “The vestibular system: multimodal integration and encoding of self-motion for motor control”. Trends Neurosci 35 (3): 185–96

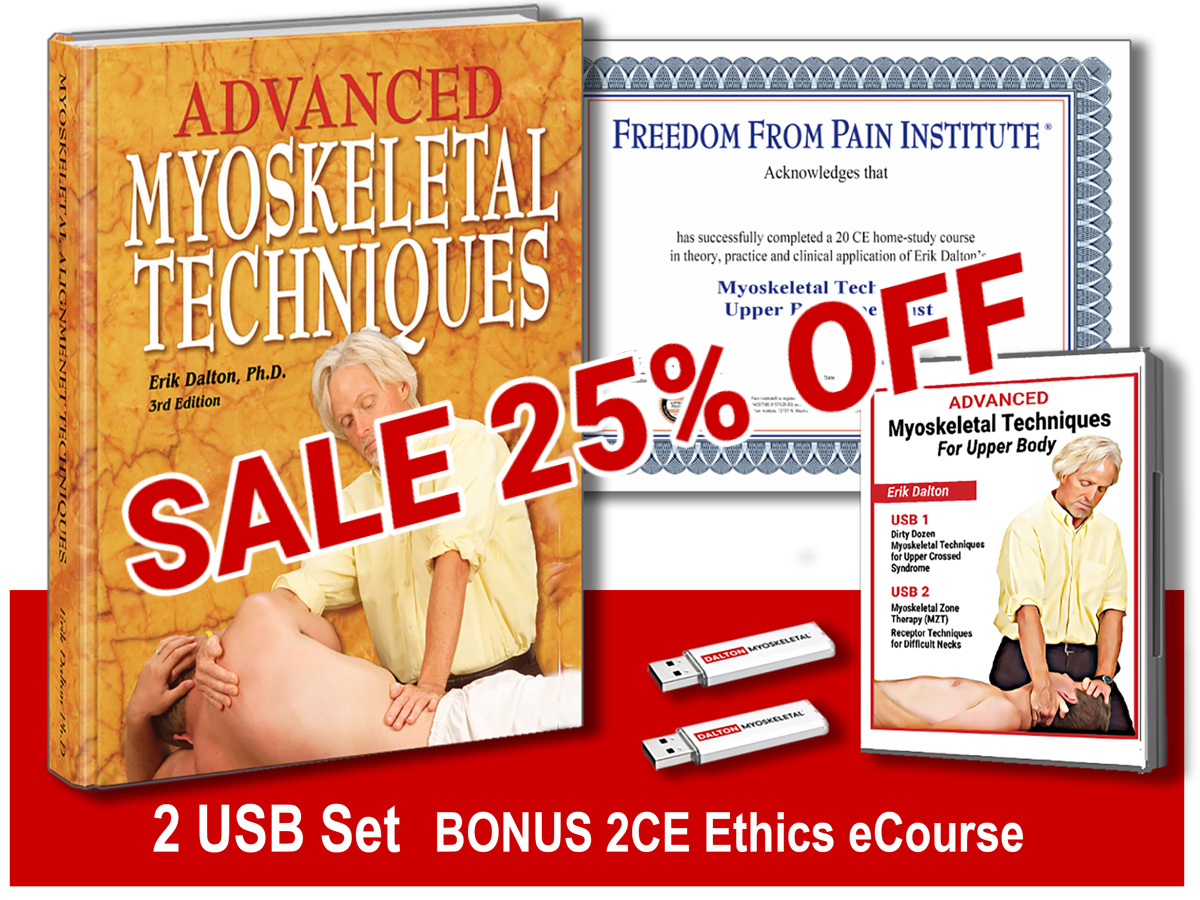

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.