Gut Gases, Bloating, and Stomach Pain: A Massage Therapist’s Guide

Gas production is a normal part of digestion. As food is broken down, naturally occurring gut bacteria produce gases such as methane and hydrogen.

In a well-coordinated digestive system, these gases trigger a natural movement pattern:

- The anterior abdominal muscles contract

- The diaphragm relaxes upward

This creates more room in the abdomen for the stomach and intestines to expand comfortably.

When the Gut-Brain Connection Misfires

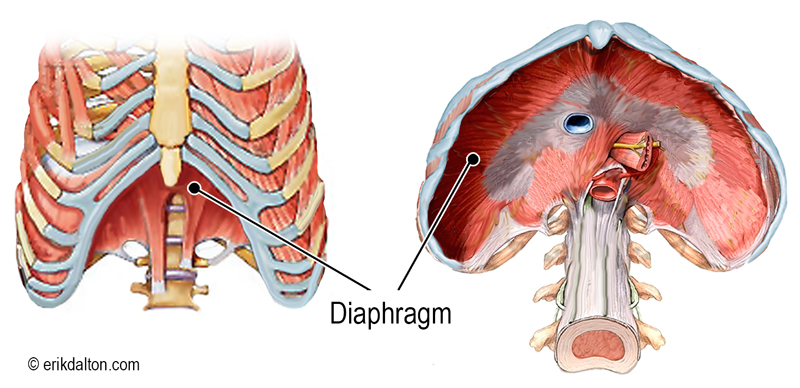

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle beneath the lungs that plays a role in both breathing and digestion (Image 2).

When the gut is full of food or gas, the diaphragm should automatically relax upward. But if gut-brain coordination is impaired, the opposite can happen: the diaphragm contracts when it senses fullness.

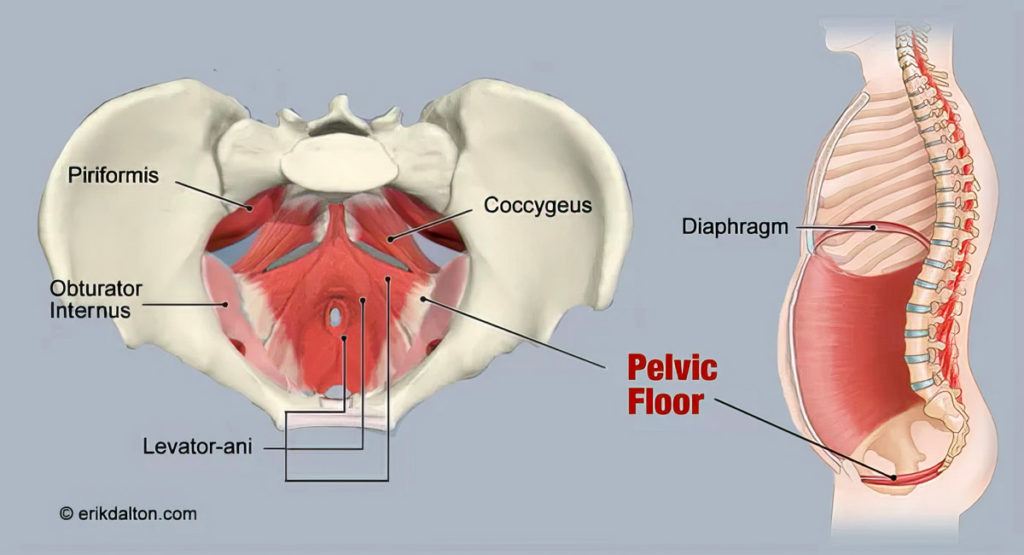

This contraction pushes gas downward instead of upward. If the pelvic floor muscles cannot relax properly, that gas can rebound upward into the abdominal cavity, triggering a visceral-somatic reflex that creates the sensation of bloating.

Pelvic Floor Tension and Belly Bulge

The pelvic floor muscles, including the levator ani, coccygeus, and piriformis, are designed to be elastic enough to expand in all directions when the abdomen fills.

In people with a chronically contracted pelvic floor, this expansion is limited. The pressure has to go somewhere, so it’s often pushed outward through the belly, creating a visible bloat or bulge (Image 3).

Clients may also report heartburn symptoms. This can occur when gas pressure pushes upward, compressing the lower esophageal sphincter, the muscle separating the stomach from the esophagus.

Myoskeletal Techniques for Bloating Relief

Bloating and distension are common complaints that can affect quality of life. Emerging evidence indicates that targeting colonic motility, gut flora, visceral sensitivity, and dietary intake is helpful in controlling such symptoms. While these interventions are important, manual therapy can also play a role in restoring comfort by improving abdominal wall and pelvic floor mobility.

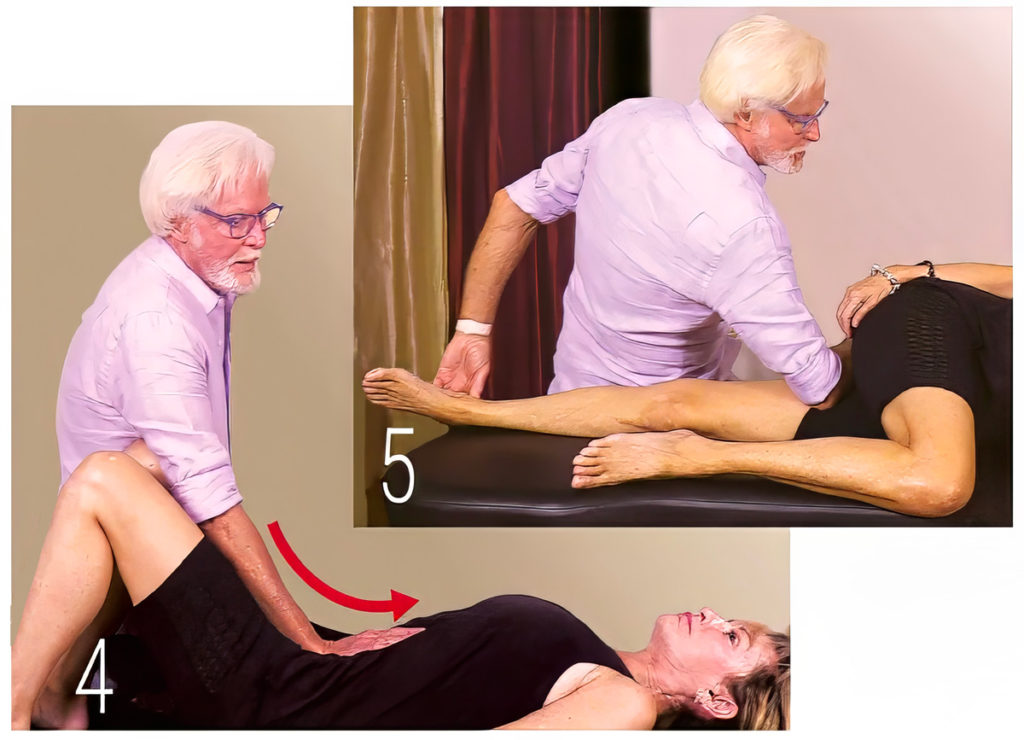

In the accompanying video, I demonstrate one of my favorite myoskeletal abdominal techniques. Here’s it is, described in text for quick reference:

- Client Position: Side-lying, with the therapist at the back. A pillow can be placed between therapist and client for comfort.

- Target Area: Begin under the descending colon (on the client’s left side).

- Why It Matters: The descending colon is a common site for stagnation. Gravity can cause the transverse colon to sag (colon prolapse), leading to reduced motility.

- Technique:

- Start with soft fingertips high on the abdomen so the client adjusts to the pressure.

- Gradually work lower toward the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS).

- Lean your body weight back slowly to lift and decompress the tissue.

- Client Response: Pregnant clients often find this particularly relieving, as it reduces abdominal pressure.

This slow, sustained approach can help move trapped gases, relieve abdominal wall tension, and improve pelvic-abdominal coordination.

Why This Works

The goal of these techniques is to restore a balanced relationship between the pelvic floor and respiratory diaphragm, a connection often referred to as the brain-gut axis.

When these structures work in harmony, digestion is smoother, gas moves more easily through the system, and bloating is less likely to occur.

Home Advice for Clients

While massage can offer immediate relief, bloating is best addressed with a combination of strategies:

- Gentle breathing exercises to promote parasympathetic activation

- Pelvic floor relaxation techniques

- Dietary awareness to reduce excessive gas production

- Hydration and movement to stimulate intestinal motility

The Takeaway for Massage Therapists

The primary goal of digestion is to get food from one end to the other as quickly as possible with maximum absorption. Massage techniques that manually teach overworked abdominal muscles how to relax and efficiently move gasses through the system will improve gut motility and strengthen peristaltic action. Though few studies exist in which bloating is a primary endpoint, I’ve personally found that musculoskeletal pelvic alignment coupled with breathing exercises to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system help improve the symptoms of belly bloat among my clientele.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.