Understanding the Critical Difference: Frozen Shoulder vs. Adhesive Capsulitis for Massage Therapists

When a client walks into your practice complaining of shoulder pain and stiffness, how do you know if you’re dealing with a “frozen shoulder” or something more specific like adhesive capsulitis? This distinction isn’t just academic terminology; it directly impacts your treatment approach and client outcomes.

Since the 1930s, healthcare providers have used the term “frozen shoulder” to describe any stiff, painful shoulder joint. But groundbreaking research by orthopedic surgeons Drs. Andrew and Robert Neviaser revealed something crucial: not every stiff shoulder is truly “frozen,” and the terms “frozen shoulder” and “adhesive capsulitis” shouldn’t be used interchangeably.

As manual therapists, understanding this difference helps us create more targeted treatment plans and set realistic expectations for our clients’ recovery timelines.

What Makes Frozen Shoulder Different from Adhesive Capsulitis?

The Cleveland Clinic’s orthopedic department offers a clear distinction that every massage therapist should understand:

- Frozen shoulder is a general, umbrella term describing any shoulder that has become stiff and painful. Think of it like saying someone “has a limp when they walk”—it describes a symptom but doesn’t tell us the underlying cause.

- Adhesive capsulitis, however, is a very specific medical condition involving the spontaneous, gradual onset of shoulder stiffness and pain caused by the joint capsule itself tightening and adhering to surrounding structures.

This distinction matters because it changes how we approach treatment. A frozen shoulder might result from rotator cuff spasm, impingement syndrome with protective muscle guarding, or micro-adhesions around the joint capsule or surrounding bursae. Each of these conditions requires different manual therapy techniques and has different recovery expectations.

The Adhesive Capsulitis Process: What’s Really Happening Inside the Joint

Understanding the pathophysiology of adhesive capsulitis helps explain why this condition can be so stubborn and why myoskeletal alignment techniques are particularly effective.

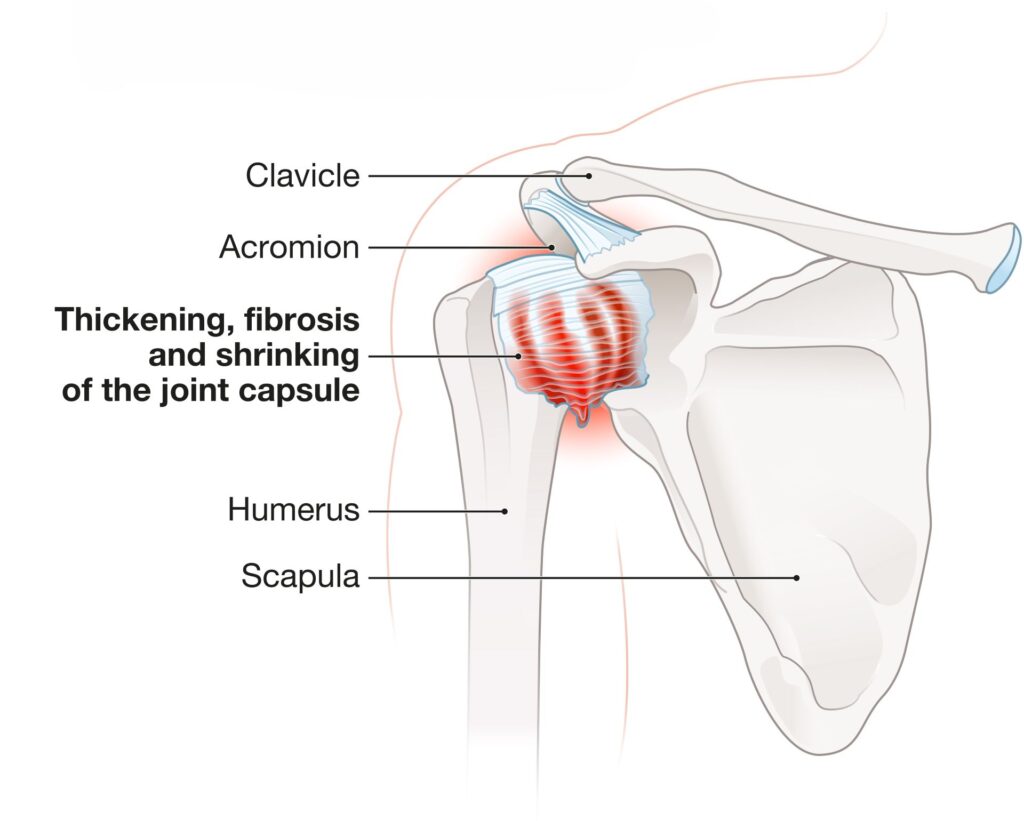

In true adhesive capsulitis, chronic inflammation attacks the glenohumeral joint capsule—the tough, fibrous sleeve that surrounds the shoulder joint. This inflammatory process causes the capsule to thicken and tighten, similar to scar tissue formation. As inflammation continues, extra folds of capsular tissue literally get stuck to themselves, creating adhesions that restrict normal joint movement.

But the problem doesn’t stop there. The inflammatory process also disrupts the joint’s natural lubrication system. Normal synovial fluid production decreases, and the joint loses its healthy supply of hyaluronic acid—the substance that keeps our joints moving smoothly. Without adequate lubrication, the humeral head (upper arm bone) can no longer slide and glide efficiently within the shoulder socket.

This combination of fibrosed capsular folds, chronic inflammation, and reduced joint hydration creates a perfect storm of restriction. The capsule loses its ability to stretch, leaving the shoulder literally stuck in a painful, limited range of motion.

Why This Matters for Your Manual Therapy Approach

Here’s why this distinction is crucial for massage therapists and bodyworkers: when a joint cannot move freely, the muscles that move it cannot function optimally either. This creates a cascade of compensatory patterns throughout the kinetic chain.

Think about it this way: if the glenohumeral joint is restricted, the body doesn’t stop trying to reach for objects or perform daily activities. Instead, it recruits other areas like the cervical spine, thoracic spine, and scapulothoracic region to compensate for the lost shoulder mobility. These compensations often lead to secondary pain patterns in the neck, upper back, and even the opposite shoulder.

This is where myoskeletal alignment techniques become particularly valuable. While we cannot directly add synovial fluid or inject hyaluronic acid into joints (that’s outside our scope of practice), we can use specific mobilization techniques to disperse existing joint fluids and improve overall joint mechanics.

The Treatment Goal: Restoring Joint Play and Centration

The primary goal when working with clients who have adhesive capsulitis or frozen shoulder conditions is to establish optimal joint play and joint centration. But what do these terms actually mean?

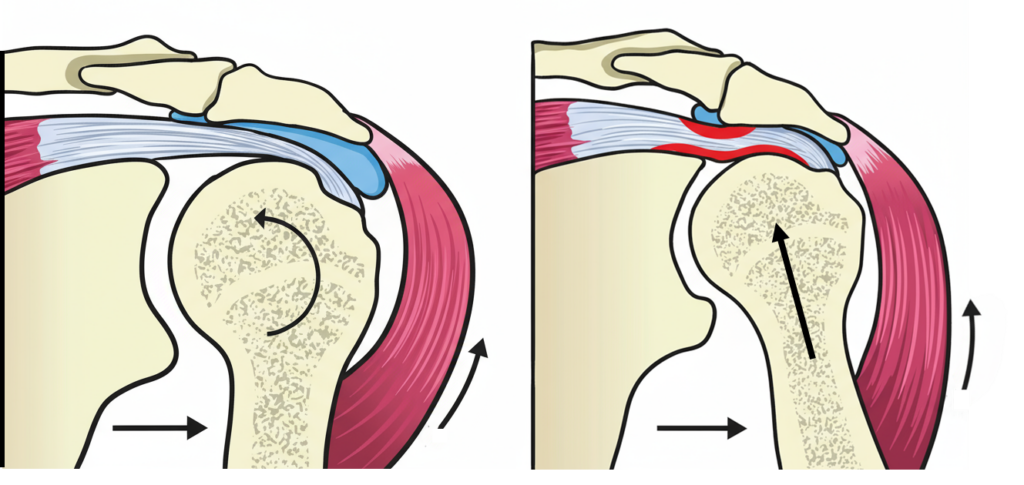

Joint play refers to the small, passive movements that occur between joint surfaces during normal motion—movements that you cannot perform voluntarily but are essential for pain-free function. Think of the subtle sliding, gliding, and spinning movements that happen automatically when you raise your arm overhead.

Joint centration means positioning the joint surfaces in their optimal alignment so forces can be transferred efficiently through the joint without creating excessive wear or strain on surrounding structures.

When we restore proper joint play and centration in the glenohumeral joint, we create an environment where the surrounding muscles can function more effectively. The deep stabilizing muscles like the rotator cuff can do their job of maintaining joint stability, while the larger mobilizing muscles like the deltoid and latissimus dorsi can generate smooth, coordinated movement patterns.

Clinical Implications for Manual Therapy

Understanding whether you’re dealing with true adhesive capsulitis versus a more general frozen shoulder condition helps guide your treatment approach and timeline expectations.

True adhesive capsulitis typically progresses through three distinct phases: the painful freezing phase (2-9 months), the stiff frozen phase (4-12 months), and the gradual thawing phase (5-24 months). Clients with this condition often benefit from gentle joint mobilization techniques, capsular stretching, and patient education about the natural progression of their condition.

General frozen shoulder conditions caused by muscle guarding, impingement, or minor adhesions may respond more quickly to targeted soft tissue work, corrective exercises, and addressing underlying postural imbalances that contribute to the restriction.

In both cases, myoskeletal alignment techniques that focus on improving joint mechanics and restoring optimal movement patterns can be highly effective. The key is matching your intervention to the underlying pathology and setting realistic expectations for recovery.

Remember, successful treatment of shoulder restrictions requires a balance between addressing local joint mechanics and considering the broader kinetic chain adaptations that develop over time. By understanding the difference between frozen shoulder and adhesive capsulitis, you can provide more targeted, effective care for your clients while avoiding the frustration that comes from treating symptoms without addressing root causes.

For more information on myoskeletal alignment techniques for shoulder conditions, explore our comprehensive course offerings and additional blog posts on treating upper extremity dysfunction.

References

- http://my.clevelandclinic.org/orthopaedics-rheumatology/diseases-conditions/frozen-shoulder-vs-adhesive-capsulitis.aspx

- Andrew S. Neviaser, MD, and Robert J. Neviaser, MD. Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, September 2011. Vol. 19. No. 9. Pp. 536-543.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.