Treating Tendinosis Conditions

by James Waslaski, LMT, CPT

Read this very informative chapter in its entirety in the Dynamic Body Textbook

The book is also a part of the 32 CE Lower Body Home-Study

Tendinosis is an overuse injury that often results from prolonged poor posture, repetitive motion, or musculoskeletal injury due to musculoskeletal imbalance. An injury of this type occurs when a tendon suffers an unnoticed, microscopic tear, and then another tear before the original heals. The owner of the tendon might use it for months without knowing that an injury is building – until many microtears build up and cause pain.

These damaged tendon tissues heal with collagen fiber formation, otherwise known as scar tissue. Scar tissue is a dense, fibrous matrix of contracted tissue that creates adhesions. Scar tissue adhesions are disorganized into multiple directions and layers, which is what makes them dense and painful. They limit the range of motion in the affected area.

The problem with the traditional treatment of tendinosis is twofold: 1) Tendinosis is often treated as an inflammatory tendinitis, and therefore, the actual causes of pain are not addressed, and 2) Conventional scar tissue mobilization often involves up to six minutes of deep cross fiber friction, which may increase pain and inflammation. The goal of tendinosis treatment is to realign the scar tissue fibers into functional scar tissue, not to treat for inflammation. We propose a treatment for tendinosis using multidirectional friction to soften the scar tissue, followed by eccentric muscle contraction to create functional scar tissue alignment.

Frozen Shoulder vs Adhesive Capsulitis

Frozen shoulder is commonly used to refer to adhesive capsulitis. However, true frozen shoulder includes a variety of pathologies that may include things like adhesive capsulitis, inner fascial adhesions within the shoulder capsule, subacromial bursitis, tendinosis, rotator cuff injuries, and other clinical conditions limiting shoulder motion.

For adhesive capsulitis, an accident, trauma, emotional or physical stress, repetitive movements, or overuse (weekend warrior) can lead to immobilization or lack of full range of motion of the shoulder. When this happens, adhesions may build up in the shoulder joint capsule and progress to adhesive capsulitis.

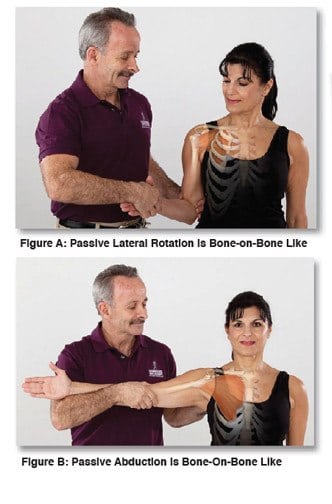

A client with this condition may have a combination of limited flexion, external rotation and abduction. The greatest restriction is usually external rotation and abduction. Early onset adhesive capsule involvement initially causes a bone-on-bone like end feel in lateral rotation, and then abduction becomes bone-on bone like, usually limiting abduction to 35 to 45 degrees.

Below are some techniques to address the joint capsule adhesions, and the inner fascial adhesions for adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. During assessment lateral rotation of the shoulder will often be limited to about 30-45 degrees with a bone-on bone like end feel. The end feel indicates it is more than just tight pectoral muscles and a tight subscapularis (Fig. A). In the more progressive capsular involvement passive assessment of abduction becomes extremely limited and bone-on bone-like (Fig. B). In advanced stages, passive abduction is limited to about 30 degrees if the scapula is stabilized.

To treat the adhesions of the actual capsule the following technique is highly successful.

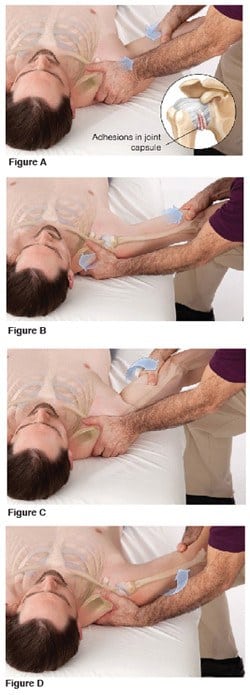

- Support and stabilize the scapula, so it does not move, from either on TOP of, or under the client’s shoulder with one hand, using evenly displaced pressure. Use the other hand to hold the arm just proximal to the elbow.

- Slowly, but firmly compress the head of the humerus into the shoulder capsule until you feel it contact the scapula. This is positional release or strain-counter-strain. This allows the capsule to shorten and the capsular adhesions to relax and potentially reset (See Fig. A).

- Then slowly but firmly traction the head of the humerus away from the scapula to stretch the joint capsule and potentially re-align the collagen adhesions in the joint capsule. Collagen mobilizes with movement (See Fig. B).

- After doing the initial compression-traction technique 3-4 times to start to mobilize the joint capsule, press the head of the humerous into the capsule again and use the head of the humerus to mobilize the inner fascial adhesions within the joint capsule.

- If the bone-on bone like end feel was in lateral (external) rotation, compress head of the humerus into the scapula and stretch the inner fascial adhesions by gently increasing lateral rotation during compression. (See Fig. C).

- If the bone-on-bone like end feel is found in medial (internal) rotation, compress the head of the humerus into the scapula and stretch the inner fascial adhesions by gently increasing internal rotation with compression (See Fig. D).

- Finish by tractioning the humerus to stretch the joint capsule (See Fig. B).

Learn more about our Lower Body Home-Study course.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.