Addressing Femoroacetabular Extension Restrictions

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when a client presents with low-back pain? Muscle spasm, nerve impingement, osteoarthritis, or maybe a disc problem? In my experience, therapists rarely link the femoroacetabular joint to back disorders, even though several studies have found a strong correlation between fixated hips and lumbar spine pathology.1

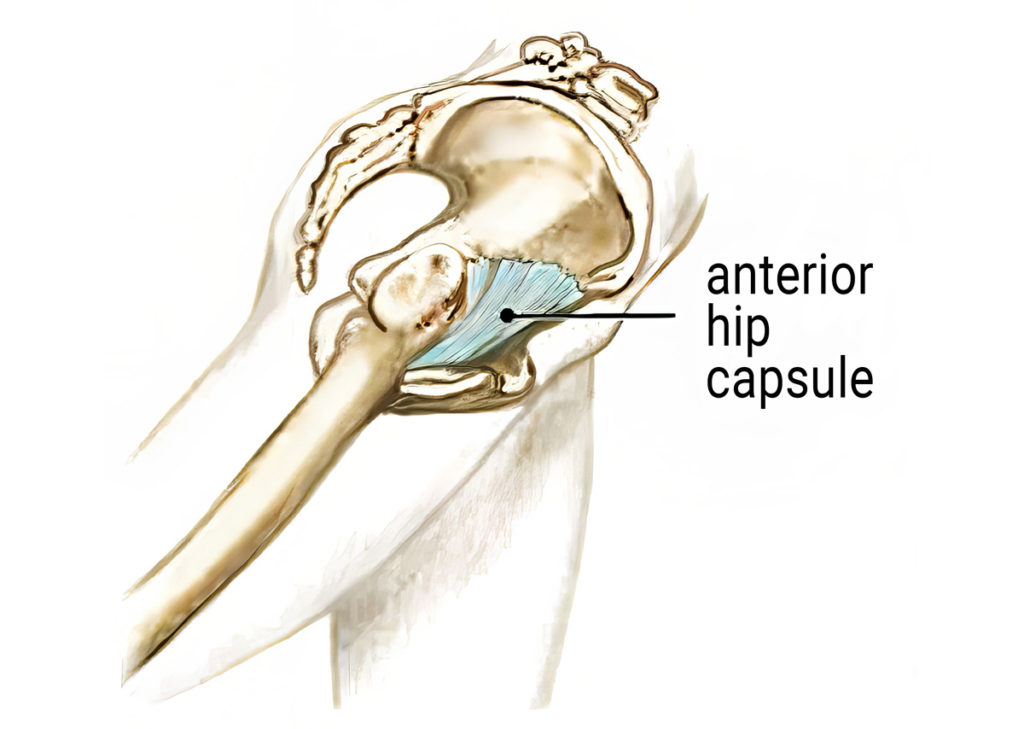

When assessing hip mobility issues, there are three things to consider. First, are the bones moving properly within the joint space, or is there an osteoarthritic bone-on-bone end-feel at end range of motion? Second, are the musculofascial tissues flexible enough to allow rectus femoris and iliopsoas to stretch the necessary length for full hip extension? Third, does the end-feel of the stretch indicate a fibrotic hip capsule (Image 1.)? In this blog, I’ll focus on the hip extension restrictions that can wreak havoc on the low back and sacroiliac joints.

What is Hip Extension?

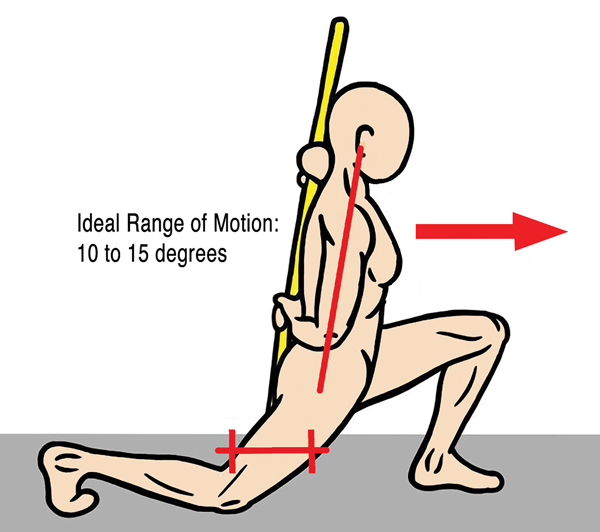

To begin, let’s clarify what is meant by hip extension. When the foot is behind the body with the knee straight, the hip is in extension, and as we walk, the hip must move 10–15 degrees beyond neutral extension to allow propulsion from the leg and foot. During normal gait, musculofascial tissues that cross the front of the hip must be of adequate length to permit fluid hip extension. Lack of extensibility of rectus femoris, iliopsoas, or the anterior hip capsule will result in noticeable gait alterations, reactive muscle spasm, or if the brain perceives tissue damage—pain.

Trick Movements

Assess & Address

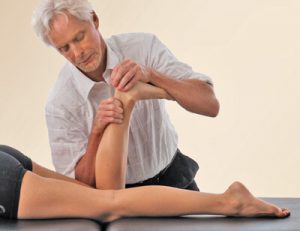

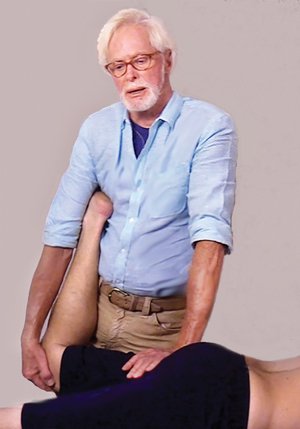

To assess the left anterior hip capsule from the prone position, begin by flexing the client’s knee to 90 degrees and grasping the leg (Image 3. ). Place your left palm just below the ischial tuberosity on the proximal femur. As you step to your left foot, your right arm will slowly bring the hip into extension while the left palm resists. Discontinue if you encounter a bone-on-bone end-feel or the client reports pain. The thigh should be able to extend about 10–15 degrees off the therapy table without pain. To address a restricted hip capsule that does not have an osteoarthritic (bone-on-bone) end-feel, ask the client to gently push their thigh toward the therapy table to a count of five and relax, then give the hip capsule a gentle stretch. Repeat three times and retest.

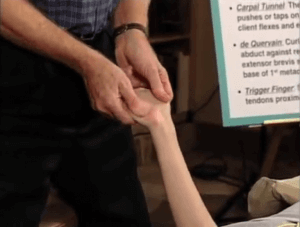

Maintain the same position to assess and stretch the rectus femoris, but this time place your left hand above the ischial tuberosity anywhere on the client’s buttocks (Image 4. ). As you step to your left foot and lift the client’s leg, the rectus femoris should be flexible enough to allow 20–30 degrees of pain-free hip extension. If a fixation is felt, raise the leg to the first restrictive barrier and ask the client to gently push their leg toward the therapy table against your resistance to a count of five and relax. Apply another graded exposure stretch to the next restrictive barrier, repeat three times, and retest.

To assess and treat for iliopsoas flexibility, the side-lying client grasps their left knee and pulls toward their chest. Place your left hand on the buttock and pull the client’s leg into extension to the first restrictive barrier (Image 5. ). Perform three contract-relax maneuvers and retest for improved iliopsoas flexibility.

Summary

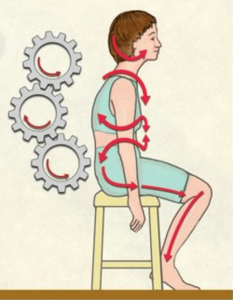

When functional gait patterns are obstructed by muscle imbalances or pain, the brain looks for a way around the block. For example, if the hip won’t fully extend, the brain may choose to hyperextend the lumbar spine to compensate for the fixated hip. Vladimir Janda labeled such compensations “trick” movements, caused by inadequate hip extension often lead to strain and pain that manifest in the lumbar spine, the sacroiliac joints, or both.

The use of skilled joint-stretching interventions, supplemented with a complementary self-care program, often brings much-needed relief for clients with achy backs. However, the clinician must always consider whether joint stretching is an appropriate strategy for a restricted hip. In clients with bony morphologic changes, mobilizations may be inappropriate, so if in doubt, refer them out.

Reference

1. Michael P. Reiman, P. Cody Weisbach, and Paul E.Glynn, “The Hip’s Influence on Low Back Pain: A Distal Link to a Proximal Problem,” Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 18, no. 1 (February 2009):24–32, https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.18.1.24; Clinton J. Devin et al., “Hip‐Spine Syndrome,” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 20, no. 7 (July 2012): 434–42, https://doi. org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-07-434; Scott A. Burns, Paul E. Mintken, and Gary P. Austin, “Clinical Decision Making in a Patient with Secondary Hip-Spine Syndrome,” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 27, no. 5 (July 2011): 384–97, https://doi.org/10.3109/09593985.2010.509382.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the "Dalton Technique Treasures" eCourse

The “Dalton Technique Treasures” eLearning course is a compilation of some of Erik’s favorite Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques (MAT). Learn MAT techniques to assess and address specific sports injuries, structural misalignment, nervous system overload, and overuse conditions. ON SALE UNTIL July 29th! Get Lifetime Access: As in all our eLearning courses, you get easy access to the course online and there is no expiry date.