The Ultimate Neck Routine: Chin Jutting, Sidebending and Translation

Here is a really effective neck mobilization routine that was taught to me by Lawrence Harvey, DO, a 96-year-old osteopathic physician. He called it C.S.T., which stands for chin-jutting, sidebending and translation. This technique trio is a dynamic companion to myoskeletal undulation, (see my Aligator Sway Undulation For Better Body Movement blog for more information) and it has been a mainstay in my private practice for more than three decades.

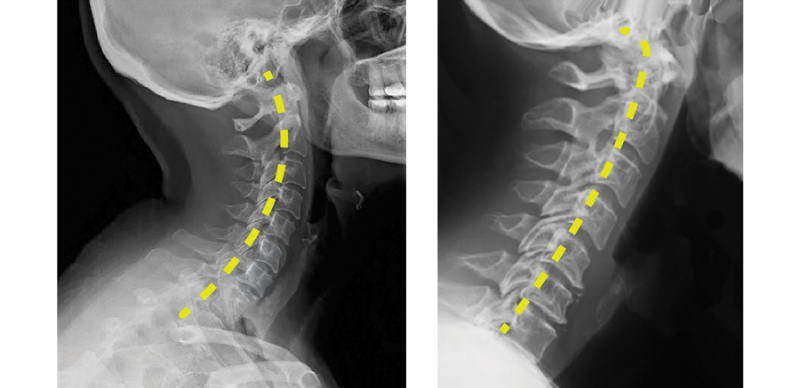

Chin-Jutting Addresses Extension Restrictions

When teaching this in class and I say, “I’m not feeling a release, so I’ll move on to sidebending and translation, and when I return, the joint will move better,” someone always asks, “Why would the restriction be better when you return?” This is an excellent question that highlights an underappreciated biomechanical concept: When you increase range of motion in one cardinal plane, it reciprocally increases range in the other two cardinal planes. For example, let us say you have a client who is unable to completely left-rotate their neck due to stiffness or pain. Instead of cranking on the neck and triggering a protective, guarded response, try using an indirect stretching technique that engages another plane of motion, such as flexion, extension, sidebending or even rotation to the opposite side. Then, come back and see if the left rotation restriction has improved. This fundamental rule of spinal biomechanics can be applied to most joints in the body. I am always surprised at how much I use it in my private practice.

Sidebending Focuses on How Facet Joints Open and Close

The sidebending technique is pretty self-explanatory. Here’s what I mean. In Image 3., I begin by sliding my right thumb under the client’s neck and contacting the right side of the spinous process at C5. With my thumb bracing the side of the joint as an anchor, my left hand right-side-bends the client’s neck over the fulcrum created by resistance from my thumb. This right-sidebending maneuver tests the ability of the C4-5 facet joints on the left to open and the right to close. I then repeat on the opposite side, moving rhythmically back and forth up and down the neck searching for soft tissue or bony restrictions.

It’s not necessary to understand the biomechanics of this maneuver or any of the following examples to obtain excellent results.

Translation Gets the Kinks Out

Translation is our entry point for learning the myoskeletal undulating technique and is a powerful way to free long-held cervical restrictions.

Translation and sidebending may appear similar, but the line of drive is in opposite directions, and this slight modification changes everything. Here is an example of one of my favorite translation techniques using what I call the carpometacarpal grip: The client lies supine. I begin by lifting the client’s head to allow the knuckle of my right carpometacarpal joint to contact the articular pillars on the right side of her cervical spine. (This can also be done using your thumb if it’s easier.) Then, as I lean my body weight onto my left leg, my knuckle gently presses against the posterolateral side of the client’s neck and my left hand helps guide the head to the left (Image 4.). Then I switch hands and repeat on the opposite side.

To keep the technique simple, I randomly move up and down the cervical spine, assessing and correcting reactive spasm and facet movement restrictions as I find them. The key point to remember when performing translation is the client’s head must not sidebend during this maneuver. The eyes always stay level during the entire routine. Therefore, when testing a non-symptomatic client, I would expect this translational maneuver to be smooth and symmetrical as the facets freely glide side to side. However, when I first began practicing how to smoothly transition from the sidebending to translation techniques, I was surprised at how much more motion was available during sidebending. Although there is reduced range of motion when performing translation, I’ve found it is often the missing link in helping clients suffering long-term radiating neck pain and localized cervical stiffness.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.