We see it all the time on sports channels. How do they do it? That golf swing is really a work of art. Requiring such a complex array of finely coordinated movements, it’s no wonder a golfer’s body is considered a ticking time bomb for acute injury or chronic pain.

Recent stats: 53 percent of male and 45 percent of female golfers suffer low back pain; 30 percent of professional golfers play injured; 33 percent of golfers are over the age of 50; and playing golf and another sport increases chance of injury by 40 percent. 1

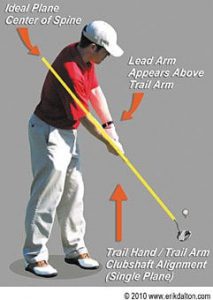

Researchers agree that a majority of injuries affecting male golfers manifest in the low back and are related to improper swing mechanics and/or the repetitive NATURE of the game. 2,3 The amateur or weekend golfer typically experiences injuries due to improper swing mechanics, whereas the sports professional is more likely to fall victim to overuse injuries from obsessive repetitive movement patterns. When a high velocity rotary force couples with trunk sidebending (the crunch factor), the golfer’s spine and deep paravertebral tissues take a beating. No wonder low back pain (LBP) is the most common golfer complaint! (Fig 1)

To hit the ball a great distance, the body must have the ability to rotate into and maintain a wide arc throughout the swing. (Fig 2) Manual therapy techniques that increase range of hip turn allow a decrease in the amount of shoulder turn, thus reducing the amount of trunk flexion and sidebending during the downswing (the most damaging moment of the swing). If golfers lack full range of hip mobility due to an adhesive capsule, powerful torsional forces will travel up the kinetic CHAIN through lumbopelvic ligaments, joint capsules and intervertebral discs.

Motion-restricted facets and damaged ligamentous tissue can neurologically inhibit deep spinal groove muscles such as rotatores, multifidus and intertransversarii leading to substitution patterns and low back instability.

Reported in the Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport (2008), University of South Australia researchers found that golfers with LBP were overly dependent on erector spinae muscles for spinal stabilization rather than allowing load transfer to be distributed among more efficient lumbopelvic stabilizers such as quadratus lumborum, transverse abdominus, multifidus, hip extensors, and thoracolumbar fascia. 4 They theorized that the brain, sensing weakness, is forced to recruit global muscles (lumbar erectors and obliques) to compensate for the weakened deep spinal stabilizers. The question is, “What mechanism causes the deep lumbopelvic stabilizers to weaken?”

Reconnecting the Disconnect

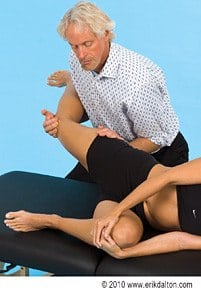

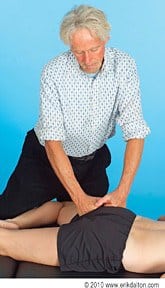

The body’s myofascial system is built from a continuous arrangement of tissues designed to function in organized patterns, not as isolated muscle groups. When operating properly, energy is efficiently transmitted via force-coupling through a reaction CHAIN rooted in the ground. Motor unit recruitment only becomes isolated to a particular muscle group when the brain senses a system disconnect and calls in “the subs.” For example, during a golf swing, if a fibrosed hip capsule were blocking energy transfer up the kinetic chain, normal force-coupling would suffer due to lack of mobility of the femoral head in the acetabulum.(Fig 3)The therapist must first mobilize the fixated joint in all three cardinal planes, and then move up the kinetic chain to assess and correct any sacroiliac or lumbar compensation that may be driving the golfer’s back pain.

Successful treatment of golf-related injuries not only requires golf swing modifications and functional rehab, but, in most cases, restoration of proper lumbar lordosis. Too much or too little curve results in excessive torsional and compressive loads through the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral junctions. The myoskeletal approach begins by correcting lower crossed muscle imbalance patterns followed by restoration of “joint-play” to fixated low back, sacroiliac and thoracic articulations.

Lower Crossed Syndrome

Developed by the legendary neurologist and rehab specialist Vladimir Janda, MD, the lower crossed syndrome represents a grouping of weak muscles and overactive or tight muscles that, together, produce a predictable low back movement pattern which often leads to injury.(Fig 4)Janda’s EMG research recorded a significant number of people developing a distinct pattern of muscle imbalance due to prolonged static posture. He noted that when a muscle is left in a shortened or contracted state for an extended period of time, reciprocal inhibition (reflex weakening of muscles on the opposite side of the body) occurs.

Many “weekend warrior” golfers sit at their job for hours on end in a hip flexed position. Day-by-day the hip flexors tighten and shorten causing reciprocal weakness of glute-max – a crucial hip stabilizer during the golf swing. No longer able to aid in pelvic stabilization, the weakened gluteals force the brain to recruit synergistic muscles like the hamstrings and lumbar erectors to assist in hip extension. When golfers present with a flabby protruding abdomen, flat buttocks and excessive lumbar lordosis, the first order of business is restoring a healthy length to hypertonically shortened hip flexors followed by hands-on fast-paced spindle-stim techniques to wake-up the weak gluteals.(Figs 5).

It’s easy to spot “lower crossed” golfers by observing their set-up posture from down-the-line. The swayed low back forms an anterior curve and, with the head down in set position, the thoracic cage becomes convex. This posture is often referred to in golfing circles as the “S-posture”. Oddly, many golfers consciously stick their buttocks out because some golf pro told them they could GENERATE more power on the downswing. In reality, once the thorax is arched and the back is swayed during set-up, the golfer can no longer “hinge” from the hips and is unable to maintain the spine in a stable neutral position. Loss of deep and middle layer core support sets the stage for future damage to lumbar and SI joint ligaments, articular cartilages, and intervertebral discs.

Summary

Rarely do humans move one muscle at a time along a single plane. Modern science reveals the brain does not recognize individual muscle activities because there is no need. Instead, the cerebral cortex maps movement patterns and coordinates the neuromyofascial net to meet the specific activity. All is well so long as information entering the central nervous system is not garbled by noxious stimuli from fixated joints, damaged ligaments, trauma or faulty ergonomics. Since the primary function of synovial joints is to transmit stress when stabilized by muscle contraction, anything that disrupts this action prevents muscles and enveloping fascia from achieving maximum leverage to move the body through a desired action such as a smooth golf swing.

Bottom Line

The greater control the golfer has over new and diverse movement patterns, the better she will perform with decreased odds of injury. In the presence of a revitalized and functionally balanced neuromyofascial system, joints and muscles operate at optimal levels of motor recruitment and synchronization. As the rate of force production and maximum acceleration improves, so does the golf swing and the NATURAL love of the sport.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.