Understanding Z-Joint Pain: The Hidden Culprit Behind Nonspecific Low Back Pain

Many clients who come in with “nonspecific” low back pain may actually be experiencing mechanical stress in the zygapophyseal joints, also known as facet joints or Z-joints—small, paired articulations on the back of the vertebrae that guide spinal motion and share load with the intervertebral discs.

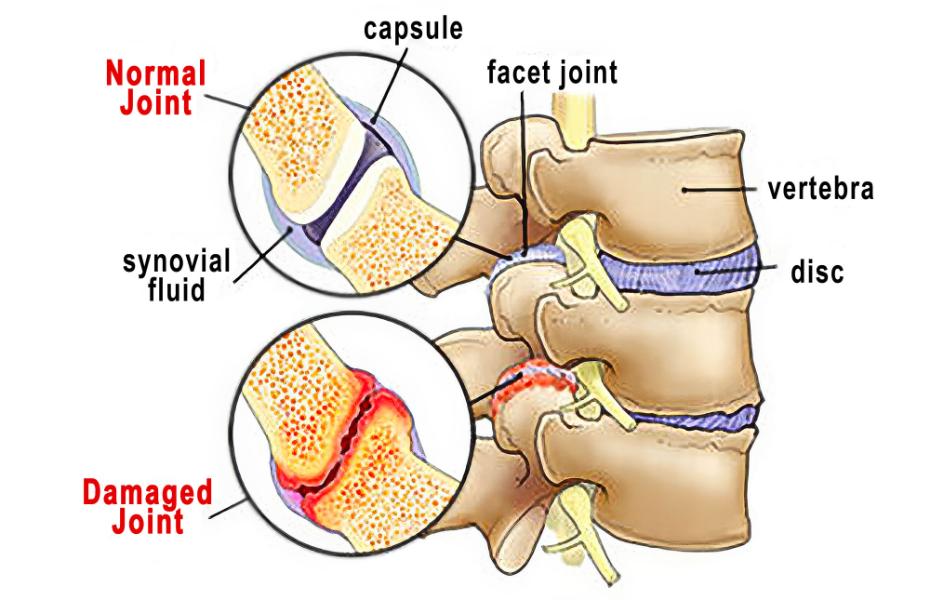

These joints are lined with cartilage, enclosed in a synovial capsule, and lubricated with fluid to allow smooth gliding between vertebrae. When healthy, Z-joints permit controlled motion, especially flexion, extension, and sidebending, while preventing excessive rotation that could damage the discs.

Unfortunately, wear and tear over time can compromise this elegant system.

Anatomy of the Z-Joints

Each lumbar vertebra connects with the one above and below through two Z-joints. Together with the intervertebral disc, they form a three-joint complex that balances mobility and stability.

- Structure: The articular surfaces are covered with hyaline cartilage and enclosed by a capsule rich in sensory nerves.

- Function: They bear roughly 20–25% of compressive load during extension and up to 50% during rotation (Adams & Dolan, 2005).

- Innervation: The medial branches of the dorsal rami transmit sensory information, explaining why inflammation here can cause sharp, localized pain near the spine.

Over time, repetitive strain, poor posture, injury, or degenerative changes can alter how these joints align and move—leading to inflammation, fibrosis, and bone spur formation.

How Z-Joint Dysfunction Develops

When cartilage thins and the capsule becomes lax or inflamed, motion becomes restricted and uneven. The resulting micro-instability leads to:

- Increased friction between articular surfaces

- Joint capsule irritation

- Chemical sensitization of the medial branch nerves

This chemical irritation can bombard the spinal cord with nociceptive signals, triggering muscle guarding and stiffness. In other words, the nervous system starts to “lock down” movement in an effort to protect the spine, ironically perpetuating the pain cycle.

Common contributors include:

- Repetitive bending or twisting

- Prolonged sitting or hyperlordosis

- Obesity or deconditioning

- Postural asymmetries or pelvic torsion

Recognizing Z-Joint Pain Patterns

Z-joint pain typically presents as localized, unilateral low back pain that may occasionally radiate into the buttock or thigh but rarely below the knee.

- Acute pain often appears intermittently and is triggered by extension or rotation.

- Chronic cases may show more diffuse discomfort with morning stiffness or pain after prolonged sitting.

Clients often report that sitting or driving aggravates symptoms more than standing or walking.

Z-joint Pain Provocation Tests

Although Z-joints are not directly palpable, tenderness in the paravertebral tissues overlying the transverse processes may indicate Z-joint involvement.

The Z-joints themselves are not manually palpable, but this maneuver is helpful in localizing and reproducing any point tenderness, which commonly accompanies Z-joint mediated pain. If the client reports localized unilateral tenderness, there are several confirmation exams I’ve found helpful, especially the Sphinx Hyperextension Test and Kemp’s Test

With Kemp’s test, reproduction of localized back pain supports Z-joint involvement, while pain radiating down the leg suggests nerve root compression.

If uncertainty remains, use the Slump and Straight Leg Raise tests to differentiate discogenic or radicular pain.

Myoskeletal Approach: Restoring Mobility and Balance

While there are few studies isolating Z-joint pain specifically, research on conservative care for nonspecific low back pain applies here as well. Manual therapy, exercise, and movement retraining can significantly reduce symptoms and improve function.

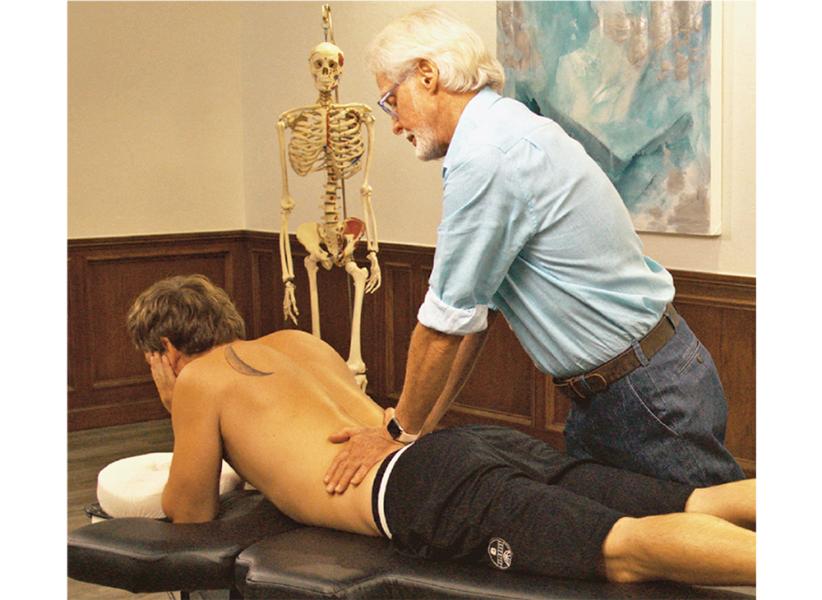

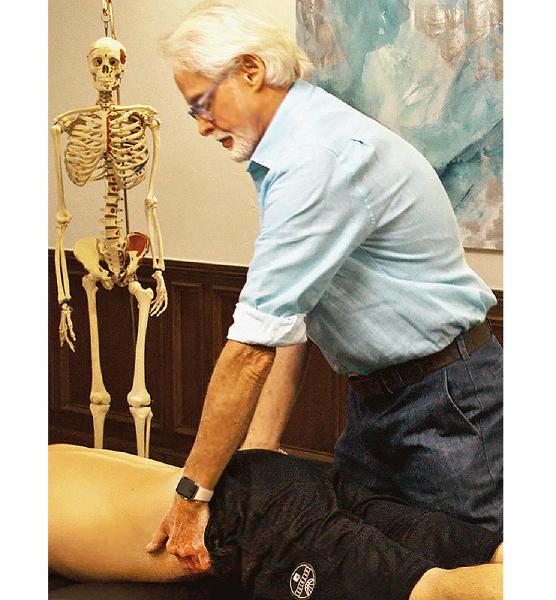

Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques (MAT) address these dysfunctions by decompressing the affected joints, rebalancing muscle tone, and restoring symmetrical movement between the spine and pelvis.

The graded exposure stretching maneuvers illustrated below are designed to bring balance to musculofascial tissues that torsion the pelvic bowl and create excessive anterior pelvic tilt. When performing these dynamic postural stretching routines, it’s best to address all connective tissues that articulate with the lumbar spine, hips, and legs and may be creating abnormal compressive loading through arthritic Z-joints.

By gently rotating the pelvis and engaging reciprocal inhibition, this Iliosacral Alignment Technique restores symmetry between the ilium and sacrum, reducing abnormal compressive loading through the lumbar joints.

Treatment Priorities

MAT treatment goals for Z-joint pain include:

- Education: Explain pain in a calm, reassuring way to reduce fear and catastrophizing.

- Postural correction: Reduce excessive lumbar lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt.

- Mobility restoration: Restore lumbar spine mobility, pelvic alignment, and pain-free movement.

- Self-care: Encourage playful, movement-based strengthening for the lumbopelvic region (e.g., pelvic clocks, bridge variations, or stability ball work).

These approaches align with research showing that movement, patient education, and consistent exercise outperform passive treatments for chronic low back pain.

Integrating Brain and Body

During each therapy session, feel free to offer advice about various sitting and standing postures that may help relieve compressive stress through the Z-joints. Cueing the client about faulty movement patterns helps bring the brain’s attention to protectively guarded areas. All our movements are governed by the central nervous system, so the brain will limit flexibility, range of motion, and mobility if it feels there is a potential danger. Therefore, it’s important to always maintain good communication with our clients and keep them actively engaged in the therapy process. While Z-joint arthritis can’t be dramatically reversed, I’ve found that exercise, lifestyle changes, and proper bodywork can contribute to a better quality of life and less discomfort.

- Adams, M.A., & Dolan, P. (2005). Spine biomechanics. Journal of Biomechanics, 38(10), 1972–1983.

- Binder, D., & Nampiaparampil, D. (2009). The provocative lumbar facet joint. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(1), 15-24.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.