by Erik Dalton Ph.D.

Last year at the Third International Fascial Research Congress in Vancouver, 800+ participants silently listened and watched as Raul Rodriques PT DO, played a video of him treating a bullfighter with a nasty scar through the thigh (Fig. 1). The audience gasped as they watched, for the first time, layers of cross-linked fibrous connective tissue give way as Dr. Rodriques’ trained hands manipulated the adhesive layers allowing them to once again glide on one another.

Through real-time sonoelastography imaging, Rodriques was able to demonstrate and explain the process of scar remodeling and how it can be effectively used to guide treatments. Although many clinicians in the audience had experienced the sensation of restoring local elasticity to injured tissue, seeing the process in real-time was spellbinding.

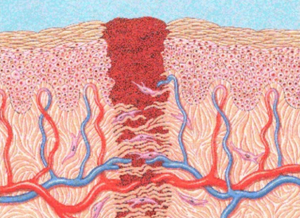

When soft tissue is injured, the body reacts by forming scar tissue (Fig. 2). Scar tissue is how the body connects and binds injured tissue. Scar tissue is indiscriminate in what it attaches to. Wherever it decides to hang out, it pulls on the surrounding tissue making the area taut and restricting blood flow. If a nerve runs through damaged muscle, fascia or visceral tissue, the entwined nerve can be pinched or pulled by the adhesion, causing it to send pain signals.

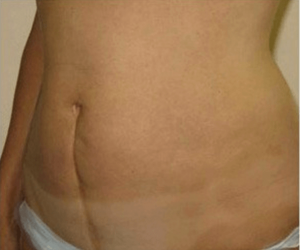

For example, C-section scars are typically located in an area where long strands can entrap pelvic, hypogastric and pudendal nerves that innervate the urethra (Fig. 3). This, in turn, may cause urethra and bladder pain. Unknowing physicians often treat this condition as bladder spasm or chronic cystitis, causing years of needless suffering. Nerves live for motion and relish the ability to slide and glide. But, as scar tissue tightens around them, they lose nutrition, become ischemic, and eventually necrotic.

Therefore, when a woman with a C-section scar presses firmly, she may experience urethral burning, urgency, or frequency. That’s why it’s important to remember that the pain and dysfunction caused by a scar is not always going to be in the area where the scar is located. Whether these adhered tissues are called crosslinks, micro-adhesions, adhesions, or scars, is all a matter of size. Whether they form ropes, sheets, or some other shape depends on how we heal, and how our body moves and pulls against existing adhesions after trauma to the tissues.

Our bodies tend to form scar tissue in response to misuse, overuse, trauma, and surgery. From a physiological standpoint, scar tissue is a natural reaction of the body to tissue damage and can be found anywhere, including skin and internal organs, or where an injury, cut, surgery or disease has taken place and the body has repaired itself. Scar tissue is composed of the same protein (collagen) as the tissue that it replaces. However, instead of the random basket weave formation of collagen fibers found in normal tissue, the collagen cross-links and forms a mangled alignment in

a single direction.1

This leads to tougher tissue that lacks the typical properties such as UV absorption, circulation, and flexibility found in normal connective tissue. These adhesions may be filmy or coarse, thick or thin. They may be small enough to join individual muscle cells, deep within a structure, or grow so large they drag down an aging person’s torso from neck to waist, bending that person forward so she literally cannot stand erect.

Adhesions require treatment because the body has no mechanism to reduce scar tissue naturally. Although the body can sometimes adapt and tolerate a certain amount of scar tissue, it will not function optimally and can cause further injury. There are many types and styles of manual therapy for treatment of scar tissue injuries and all are probably helpful to some degree. I’ve found that the sooner therapy is started, the more effective it can be. Although “semi-fresh” scars respond more quickly to treatment, hope exists for old injuries too.

Manual therapy methods such as Myoskeletal Alignment Technique (MAT) may be effective in helping restore function to inflexible tissues, thus normalizing cellular metabolism and organ function. Much like the tractioning, compression, shearing, and torsioning maneuvers used by Dr. Rodriques with the gored bullfighter, MAT utilizes varying degrees of pressure and depth to release adhesions and soften or “functionalize” tough, fibrous connective tissues.

References

- Sherratt, Jonathan A. (2010) Mathematical Modeling of Scar Tissue Formation.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.