As seen in the NEW! Pain Detectives In Ireland eCourse

Boost your Ability to Solve Pain and Injury Puzzles

Like many of you, clients seek my services primarily for pain and injury relief, and I’m always experimenting with new ways to help them feel better, move better, and stress less. While traveling to teach a myoskeletal workshop in Ireland, I had an idea for a “pain detective” game I thought the students might enjoy. The original thought was to have the class pair up and ask each student to secretly write down their three primary pain or injury complaints in order of severity, with the “main pain event or key lesion” being number one. The therapists would then take turns trying to solve their partner’s pain puzzle using only body-reading and physical palpation assessments. While it didn’t quite turn out the way I envisioned, the game was fun and helped sharpen our skills.

Key Points

- The pain detective game may help you sharpen your palpation assessments and clinical reasoning skills.

- Use ART (asymmetry, restriction of motion, and tissue texture abnormalities) to more quickly identify how one side of the body moves in relation to the other.

The Rules of the Pain Detective Game

Rule No. 1: The working therapists (detectives) were not allowed to perform a history intake or question their partner about the causality or severity of their pain. However, for safety purposes, all known medical pathologies were to be disclosed before beginning the pain game.

Rule No. 2: The detectives were encouraged to employ any postural, biomechanical, or orthopedic assessments to try to solve the pain puzzle.

Rule No. 3: If performing pain provocation tests via palpation, the detectives were permitted to question their partner about the degree of pain in an area being palpated but were not allowed to ask if the tenderness elicited referred pain.

Rule No. 4: If a movement restriction or tender spot was discovered during assessment, the detectives were allowed to treat the area, reassess, then ask their partner if they felt less pain or perceived freer movement.

Rule No. 5: After a strict 40-minute time limit, the detectives were required to verbally disclose their educated guesses as to the top three pain complaints. At that time, their partner would present the written list, discuss the findings, switch places, and repeat the pain game experiment.

Reconsidering my plan

After recovering from jet lag, I realized it might not be a great idea to conduct this experiment with a large group of therapists before attempting it myself. So, I decided to enlist the help of senior myoskeletal instructor Aubrey Gowing, the guest presenter at the Dublin, Ireland, event. At the end of the three-day workshop, my Freedom From Pain Institute staff recruited four models to join us the next day at Aubrey and his sister Alison Kavanaugh’s Holistic College of Dublin studio. Once there, we decided it might be interesting to film the pain detective experiment to document whether we identified each participant’s three major pain or injury complaints.

Assessment Props offer Important Clues

Since the pain game rules prevented us from performing a history intake or questioning the models about their primary pain complaints, we quickly realized we needed props to gather basic information. Fortunately, Aubrey’s classroom already had a mounted postural grid chart, and I remembered I had packed two matching digital scales for use in the workshop to demonstrate weight-differential effects on postural compensations.

In Image 1, Aubrey and I are observing for posturofunctional deviations and weight distribution differences using the two scales and comparing the findings with what we were seeing on the postural grid chart. Researchers say most people exhibit a right motor-dominant pattern and bear more weight on that side, which causes the right leg to be 4.6 percent larger in volume, and we found this to be generally true.1 The props helped pinpoint the model’s gross defects and offered important clues to possible areas of excessive weight-bearing that might trigger soft-tissue and joint strain. Yet, with two therapy detectives attempting to perform orthopedic, postural, and pain provocation assessments, we soon recognized the need for a more simplified screening method.

ART to the Rescue

We decided to streamline the assessment process using a method I discussed in a past article I wrote for Massage & Bodywork, “Put ART to Work in Your Practice” (November/December 2022 Issue). ART is an osteopathic acronym that stands for asymmetry, restriction of motion, and tissue texture abnormalities. Focusing on ART allowed us to more quickly identify how one side of the model’s body was moving in relation to the other and to then test if the movement restrictions were related to the tenderness they may be feeling during palpation.

When assessing for tenderness, Aubrey and I typically began by performing digital pain provocation tests of suspected muscles, tendons, ligaments, joint capsules, bursa, and joints. These tests offered clues as to whether the palpated tissue may be under load, but without verbal feedback, we weren’t always able to determine if the tender area was one of their three primary complaints or just compensations due to tension, trauma, or weak posture.

That’s when ART really came in handy. By observing, palpating, and motion testing the whole person rather than chasing the pain, we were able to better trace the effects back to the originating cause — and gain context as to how and why the tissues were under load in the first place. (Image 2.)

Summary

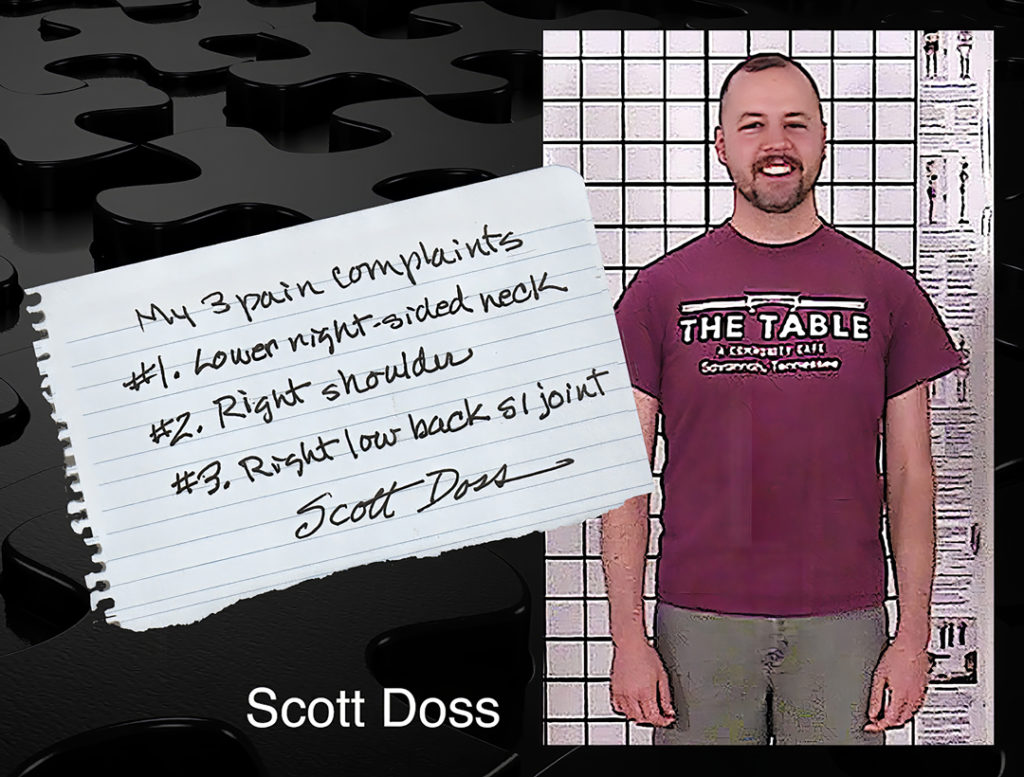

Although Aubrey and I weren’t always able to identify a key lesion that may have been at the root of their problems, we were both surprised and delighted that we correctly identified all 12 areas that matched the list of pain complaints the four subjects had recorded. Image 3. is a sample list of pain complaints one of our participants submitted.

This pain detective game turned out to be fun for all, and it really helped sharpen our palpation assessments and clinical-reasoning skills. I suggest trying it either in your private bodywork practice or with a fellow therapist. I believe it will greatly empower you to move through the body with more confidence and with greater therapeutic outcomes.

References

1. J. P. Chapman, L. J. Chapman, and J. J. Allen, “The Measurement of Foot Preference,” Neuropsychologia 25, no. 3 (1987): 579–84, http://doi.org/10.1016/00283932(87)90082-0.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.