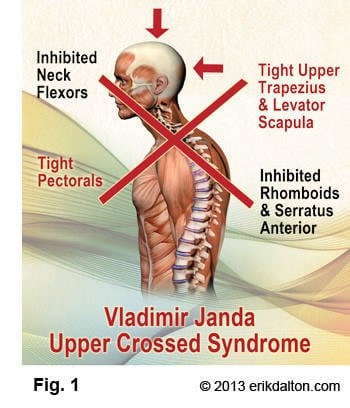

Upper Crossed Syndrome (UCS) may generally be described as the weakening and lengthening of the posterior chain of upper-back and neck musculature, and the tightening and shortening of the anterior and opposing musculature. Forward head postures that accompany the Upper Crossed Syndrome (Fig. 1) may result from poor sleeping habits, driving stress, text-neck, whiplash, and faulty breathing patterns.

The UCS is based on Dr. Vladimir Janda’s pioneering research work in understanding the body’s predictable patterns of muscular compensation and postural imbalance. His observations led him to believe that a poor postural base creates faulty movement patterns that contribute to habitual overuse in isolated joints, while minimizing normal movement in others, thus creating a self-perpetuating cycle of dysfunction and eventual injury.

The UCS is based on Dr. Vladimir Janda’s pioneering research work in understanding the body’s predictable patterns of muscular compensation and postural imbalance. His observations led him to believe that a poor postural base creates faulty movement patterns that contribute to habitual overuse in isolated joints, while minimizing normal movement in others, thus creating a self-perpetuating cycle of dysfunction and eventual injury.

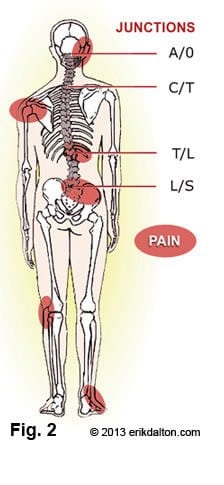

As seen in Figure 1, UCS tightness of the upper trapezius and levator scapula on the dorsal side crosses with tightness of the pectoralis major and minor. Weakness of the deep cervical flexors ventrally crosses with weakness of the middle and lower trapezius. This pattern of imbalance creates joint dysfunction, particularly at the occipitoatlantal joint, C4-C5 segment, cervicothoracic joint, glenohumeral joint, and the T4-5 segment. Janda noted that these focal areas of stress within the spine correspond to transitional zones in which neighboring vertebrae change in morphology (Fig. 2).

Janda determined that a tight, shortened muscle can inhibit its opposing muscle, i.e., tight pectoral muscle reciprocally weakens serratus anterior. Janda also found that many times just stretching the tight muscles allowed the opposing muscles to function better. Therefore, the first step to counter Upper Cross Syndrome in Myoskeletal Alignment is to stretch the pectoral muscles.

Compensatory Rotator Cuff Injury

During these warm summer months, swimmers, runners and cyclists with UCS may be prone to injury as the forward head carriage exacerbates the faulty mechanics causing excessive wear to tendons, ligaments and joints.

Additionally, UCS may also impede performance as the sternum and diaphragm are squashed by a depressed and compressed ribcage. A forward head posture also creates strain at the musculofascial attachments of the shoulder and shoulder blade. As the shoulders round, the scapulae tilt forward and “flare-out” into abduction producing a rounded shoulder appearance.

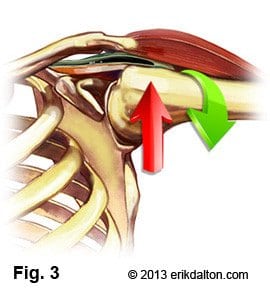

The problem with a rounded shoulder posture is that the mechanical axis of rotation of the glenoid fossa becomes altered. The humerus now requires additional stabilization from muscles that are typically at rest, such as the upper trapezius, levator scapulae, pectoralis minor, subscapularis, supraspinatus muscles. Postural overdevelopment of these muscles creates a deltoid shear (crossing of rotator cuff under AC joint), leading to shoulder impingement, tendinitis and bursitis syndromes (Fig. 3).

Specific postural changes are seen in UCS, including forward head posture, increased cervical lordosis and thoracic kyphosis, elevated and protracted shoulders, and rotation or abduction and winging of the scapulae. As stated above, these postural changes decrease glenohumeral stability as the glenoid fossa becomes more vertical due to serratus anterior weakness leading to abduction, rotation, winging of the scapulae and often rotator cuff tearing.

There is also the issue of motor memory. People literally develop a memory of an injury or the pain associated with it, and keeps it active, as though they were still injured. This locks them into the very posture that afforded them avoidance at that time. I’ve had a number of clients over the years that abandon their home retraining exercises before the motor memory has had a chance to change. Soon, they’re back in the office complaining of neck pain or rotator cuff irritation.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.