Mired in Controversy

I’m aware this may be an unpopular statement, but I don’t completely agree with the idea of pain-free bodywork.

In an environment that promotes relaxation under the guidance and reassurance of a qualified bodywork professional, I believe a client’s brain can be trained to associate slow, precise, graded-exposure stretching maneuvers with security instead of pain. Pain is essentially a threat warning, so pain exposure therapy (PET) requires time for the brain to process these bodily changes.

In the myoskeletal application of PET, therapists and clients use active feedback while working at the feather edge of the client’s painful barrier, just above comfort level. Muscle energy, fascial hook, and pin-and-twist maneuvers, such as those demonstrated in Images 1–3, encourage the client to engage the painful barrier with active movements and gradually push the discomfort level a bit further with each repetition. By progressively introducing stretch to areas that have been problematic in the past, the nervous system begins associating the new movement with safety instead of pain.

Throughout a series of sessions, I’ve noticed a marked decrease in protective muscle guarding, and an increase in pain tolerance and joint range of motion when following these key guidelines:

- Create a safe environment with active client feedback and participation

- Work at the feather edge of the painful restrictive barrier, and introduce graded-exposure stretches to diminish discomfort

- Include novel stimuli during sessions by exploring new movement patterns that attract and hold the brain’s attention

- Offer home-exercise suggestions that reinforce the new movement patterns

How does Pain Exposure Therapy work?

We’ve all seen how pain can reduce strength, flexibility, and endurance, as well as create a sense of fatigue. The brain is trying to do anything it can to avoid what it believes may cause injury. With a built-in adaptive mechanism, it can determine whether the body needs less or more protection at any given time. There is little doubt that traditional stretching routines produce an immediate increase in muscle extensibility due to the viscoelastic nature of muscle, but these effects quickly dissipate. The more permanent extensibility seen in PET is likely the result of two factors: the client’s willingness to tolerate the discomfort associated with stretch, and muscle, ligament, and joint pain gating.

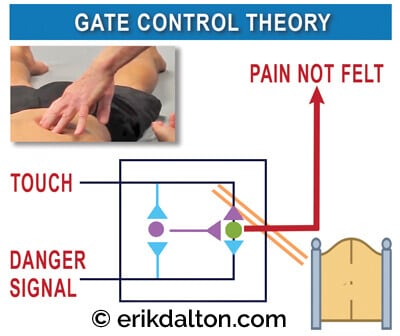

According to the gate control theory, pain sensations are affected by descending modulatory influences from the brain, which can make the stretch either more or less sensitive to pain (Image 4)1 When danger-signaling nociceptors are stimulated by excessive stretch, mechanical compression, and inflammation, the stimuli are fast-tracked to different parts of the brain. The brain then quickly interprets the information based on things such as prior therapeutic experiences, elevated mood, and confidence from positive expectations of stretch benefits. If performed correctly, afferent input from muscle and joint mechanoreceptors during a stretch can interfere with danger signals and inhibit an individual’s perception of pain.

For example, during a forward-bending hamstring stretch, the farther the person bends forward (stretch torque), the closer they can reach toward their toes. This results from mechanoreceptive pain gating in the hip and low-back joints, as well as an increased willingness to tolerate the discomfort associated with the stretch. The controlled manipulation of tissue and facilitated movement during PET offer added safety from overstretching into the painful barrier by providing tactile feedback that prevents the brain from guarding the area with protective muscle spasms.

Several steps can be taken to further avoid exasperating a client’s symptoms during PET. First, practitioners must develop subtle palpation skills to differentiate quality, range, and end-feel when assessing soft tissues such as ligaments, muscles, fascia, and particularly joint capsules. Mentally ask yourself the following questions: During end-range of motion, does this tissue have a boggy, leathery, spasmodic, or hard end-feel? When comparing side to side, are there areas of bind in one limb and greater ease of movement in the other?

Efficiency of movement and improved function are the desired outcomes of any bodywork strategy. Tension, trauma, and even overly aggressive bodywork can result in excessive soreness and stiffness, which compromises fluid movement. Such stiffness typically results from nonoptimal neuromuscular firing due to altered brain maps, rather than passive stiffness based on adhesions, scar tissue, or degenerative changes. Remember that the body’s physical and mental states interact bidirectionally, so we can decrease pain by moving better, and we can move better by decreasing pain.

Femoral Nerve Mobilization Technique (L2- L4)

- Client lying on right side, uses both hands to grasp her bottom knee towards her chest

- Therapist’s right hand grasps client’s left ankle and his left hand grasps her knee

- Therapist steps behind client’s knee as it is brought into flexion

- With left hand on her knee and his right hand securing her ankle, the therapist can create knee flexion or hip extension

- Therapist gently extends client’s hip to painful femoral nerve barrier and backs off to the inter-barrier zone

- The client tucks her chin to traction the femoral nerve

- To floss the nerve distally, the therapist gently adds knee flexion as the client brings her head back to neutral

- In hypermobile clients, the therapist removes his right hand from ankle and places it on client’s hip

- A counterforce is created as the therapist extends clients hip by pulling with is left hand and resisting with his right. Knee flexion can also be added if needed

Repeat this pain-free nerve flossing technique 5 – 10 times and reassess for reduced femoral nerve pain. Repeat on opposite leg.

Summary

A PET desensitization approach is aimed at normalizing sensation by providing consistent stimulus to the affected area for short periods of time. The brain will respond to this sensory input by acclimating to the sensation, thereby gradually decreasing the body’s pain response to the particular stimuli. Good clinical assessment and the appropriate application of PET, combined with self-care advice, can be successfully used in conjunction with other therapies to build an effective pain-management program.

Reference

- R. Melzack and P. D. Wall, “Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory,” Science 150 (1965): 971–9.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.