Restoring Function to Inflexible Tissues

Scar tissue is nature’s response to tissue damage (Img. 1). This fibrous material of human healing is composed of the same protein (collagen) as the tissue it replaces, but lacks the ultraviolet absorption, circulation, and flexibility of the original tissue. Instead of the random basket-weave design found in normal tissue, scarred collagen forms a mangled alignment of crosslinks that bind themselves in a single direction.1

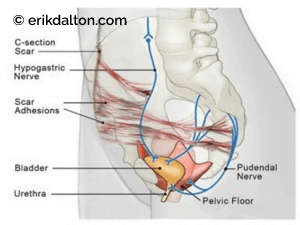

Nerves live for motion and relish the ability to slide and glide. If a nerve runs through impaired muscle, fascia, or visceral tissue, the entwined nerve can be pinched or pulled by the fibrous scar, causing pain signals to be sent. For example, scars sometimes grow long, tentacle-like strands called adhesions. It’s not uncommon for the adhesions from a Cesarean-section scar to entrap nearby hypogastric and pudendal nerves feeding the bladder and urethra (Img. 2). This, in turn, may cause referred nerve pain that mimics, and is often treated as, cystitis. Consequently, when a woman’s fingers press firmly on a C-section scar, she may experience urethral burning, urgency, or frequency. That’s why it’s important to remember that pain caused by a scar may be referred far from where the scar is located. Moral of the story: don’t chase the pain.

Through real-time sonoelastography imaging, Rodríguez was able to visually demonstrate the process of manual scar remodeling and how it can be effectively used to guide massage and bodywork treatments. Although many clinicians in the audience were well acquainted with the palpatory sensation of restoring local elasticity to injured and sometimes painful (neurologically sensitized)) tissue, witnessing the process in action was spellbinding. According to a 2013 study conducted by Rodríguez and Galán del Río, fascia is the “skeleton of muscle fibers organized as a network and may be responsible for some of the pathophysiology and healing processes of muscular injuries.”2

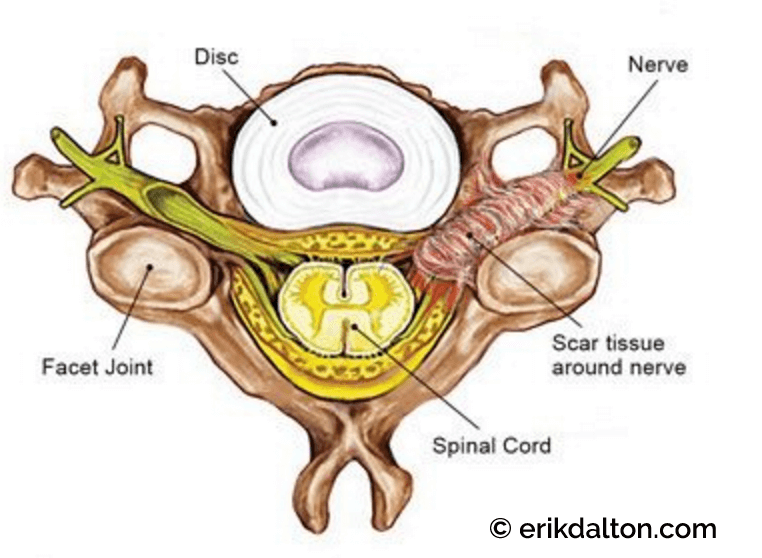

But injury is not the only cause of scar tissue. In clinical practice, we commonly palpate fibrous connective tissues associated with plantar fasciitis, tennis elbow, and rotator cuff pain. When scar tissue arises near a nerve root, it is referred to as epidural fibrosis (Img. 3). This is a frequent occurrence in those experiencing failed back surgeries.

Adhesions are bands of scar-like tissue that form between two surfaces inside the body and cause them to stick together. When the scar extends from one tissue to another, usually across a virtual space such as the peritoneal cavity, the body deposits fibrin onto the injured tissues. The fibrin acts like a glue to seal the injury and builds the fledgling adhesion. At the sites where abdominal adhesions occur, scar-tissue tentacles sometimes grab a piece of the small intestine. As internal pressure causes the intestine to twist and tangle on itself, peristaltic action is stalled and the putrefaction process begins.

Adhesions require treatment because the body has no mechanism for mobilizing these strands of scar tissue naturally. Although the body can sometimes adapt and tolerate a certain amount of adhesive scar tissue, it will fail to function optimally, predisposing itself to repeated injury. There are many types and styles of manual therapy for the treatment of adhesions. Clearly, the sooner therapy begins, the more effective it will be. Semifresh scars respond more quickly to treatment, but hope still exists for old injuries, too, as seen in Rodríguez’s brilliant sonoelastography demonstration.

The goal is to restore function to inflexible tissues and normalize cellular and organ metabolism. Much like the stretching and torsional maneuvers used by Rodríguez on the injured bullfighter, hands-on modalities using varying degrees of pressure and depth may also help soften and functionalize tough, fibrous connective tissues resulting from an abdominal scar.

In Img. 4 and Img. 5, fingers and thumbs search for underlying adhesions and slowly work to free entrapped nerves responsible for referred pelvic pain patterns. To speed recovery, teach your clients how to perform these simple techniques at home.chniques at home.

References

- Jonathan A. Sherratt, “Mathematical Modeling of Scar Tissue Formation,” Department of Mathematics, Heriot-Watt University (2010).

- Raúl Martínez Rodríguez and Fernando Galán del Río, “Mechanistic Basis of Manual Therapy in Myofascial Injuries. Sonoelastographic Evolution Control,” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 17, no. 2 (2013): 221–34.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.