A Case Study

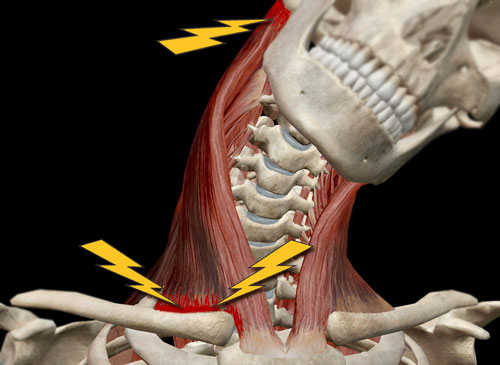

Luke was referred by his personal trainer for neck mobility issues resulting from a direct blow to his left shoulder during football practice six months earlier (Image 1.). Although most of his cervical brachial plexus pain had subsided, he was still forced to turn his entire body to look into his rearview mirror while driving. Upon seated examination, Luke’s passive range into right cervical rotation, flexion, and extension was normal, yet he could only manage 30 degrees of left cervical rotation and sidebending.

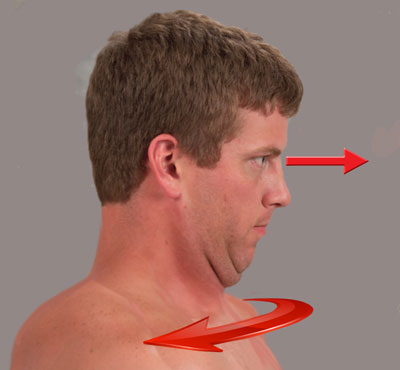

To address the left rotation restriction using movement enhancers, my left hand slowly left rotated Luke’s head to the first (non-painful) restrictive barrier as my soft right fist resisted this effort creating a counterforce between the two hands (Image 2.).

I asked Luke to take a deep breath and gently right-rotate his head against my hand resistance to a count of five and relax.

With my right fist still pinning the hypertonic upper traps, scalenes and splenius cervicis muscles, Luke was asked to look over his left shoulder while actively left rotating his head against my (pin hand) resistance.

This routine was repeated three times.

Then to help reassure his brain it could now move more safely, I removed my hands, and Luke was instructed to turn his eyes and head left as far as comfortably possible.

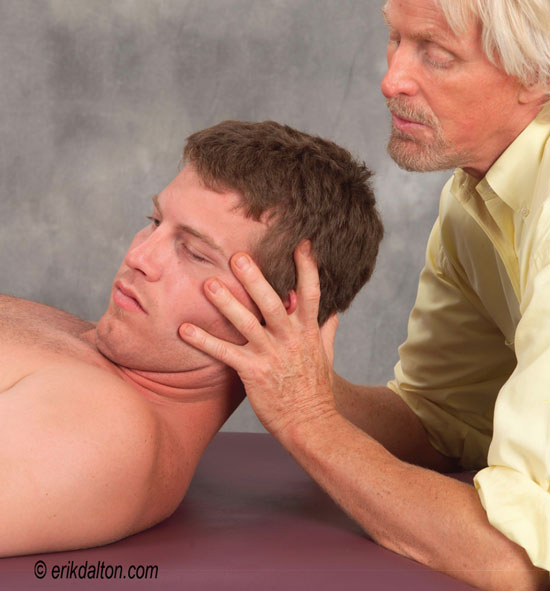

This MAT maneuver helped regain some of Luke’s lost range of motion, but as I observed him actively left rotating, I noted visible reactive muscle guarding in his right SCM as he attempted end range. To address his SCM spasm using movement enhancers, Luke assumed a left sidelying position and I performed the graded exposure stretching technique (GEST) described in Image 3.

Following this routine, Luke was asked to sit and repeat the head rotation test, which showed that he was still restricted near end range. So, to determine if the brain was protectively guarding or if there were additional nerve damage issues from his football trauma, I decided to try an assessment to trick Luke’s brain.

I asked Luke to focus on an object directly in front and with his chin tucked, slowly begin left and right rotating his shoulders (Image 4.) As Luke’s shoulders reached the end range of the right rotation, I asked him to stop and observe what his head and neck were doing. He was astonished when he realized how far left his head was turning and that he could accomplish this simply by right rotating his shoulders. I suggested he practice this brain-based self-care exercise at home while observing himself in the mirror.

Now that I knew that Luke’s brain was still protectively guarding that old injury, I began palpating up and down his cervical spine. As my fingers and thumb reached the base of the occiput, I noticed considerable right-sided suboccipital tone particularly in the inferior oblique muscle on the right. Notice in Image 5., how I use an optic-nerve (eye) enhancer to help relieve the suboccipital spasm that was preventing atlas on axis joint rotation.

During the three weeks of Luke’s treatment, I experimented with many myoskeletal techniques and enhancers, but those described in this article proved to be the most effective. Luke’s commitment to his MAT enhancer homework was a big plus in his recovery, which shortened his time with me and got him back to the sport he loved.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.