Much has been written about loss of flexibility and range of motion due to fascial contractures, trigger points, spasmodic muscles and the like, with less emphasis on the neurology that may be initiating these soft tissue changes. Here are some thoughts on how injuries to joint capsules and spinal ligaments can reflexively spasm neighboring tissues leading to decompensation, altered movement patterns and pain-spasm-pain cycles.

When the brain senses bony instability or ligamentous damage in-and-around the spine, information is collected so split decisions can be made to determine the extent of threat to the individual and what actions (if any) need to be taken. Layering the area with protective myospasm is one such decision. It’s the brain’s reflexogenic attempt to prevent further insult to the injured tissues. By ‘splinting’ the area with spasm, the hypercontracted (shortened) muscles, ligaments and fascia effectively reduce painful joint movements. Splinting is a common form of protective guarding clinicians address day-in and day-out… but how does it develop and how should we treat it?

Recently, a chiropractic buddy referred a client named Hank who came in carrying a diagnosis of chronic muscle spasm. During Hank’s history-taking, he related a story of a bending/twisting incident that occurred while lifting his toddler out of the back seat of the car. Apparently, this asymmetric spinal loading maneuver resulted in ‘stabbing’ back pain which almost brought him to his knees. After a few treatments, the chiropractor decided Hank’s back was too locked up and needed some deep tissue and stretching work. His treatment plan was to have me ‘dig out’ the spasm and then he would mobilize the fixated spinal joints.

Observations during gait revealed a lack of smooth cross-patterned movement between Hank’s torso and hips and very little “lift” in his antigravity spring systems1. In fact, he wobbled from side-to-side much like John Wayne’s Rooster Cogburn character in “True Grit”2(Fig 1). The chronic low back pain had disrupted Hank’s hip abduction firing order pattern forcing him to recruit the ipsilateral QL (instead of gluteus medius) to hip-hike and lift the swing leg. It was obvious that Hank’s lumbar spine had been locked with spasm for some time but elbowing the spasm didn’t seem to be the answer.

History and Motion-Testing

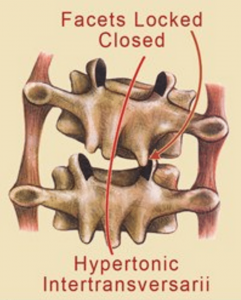

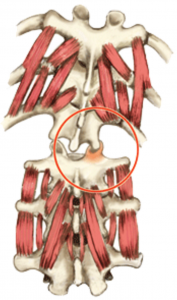

Hank’s back pain history and motion testing results suggested an unstable spine that had not been allowed proper healing time due to overstretching and chiropractic adjustments. The heat emanating from Hank’s back indicated an active inflammatory process at work…probably due to articular cartilage derangement and/or spinal ligament damage. When pain and inflammation bombard the central nervous system, joint reflexes are stimulated that can disrupt normal low back myo-mechanics. To test, I asked him to slowly forward bend as I palpated for low back asymmetry. This maneuver intensified Hank’s dull, aching pain on the right side at about L4-5. As he reached his end range of trunk flexion, I applied a little overpressure which caused the right L4 transverse process to posteriorly rotated against my palpating thumb suggesting the L4 facets on the right were unable to disengage from L5 (Fig 2). To verify, I had him stand straight and try to right sidebend his torso. Normally, I’d expect the L4 transverse process to left rotate against my thumb during this maneuver, but the joint mechanoreceptors refused to take the joint beyond its painful restrictive barrier by inhibiting the left spinal side-benders…particularly QL (Fig 3). While motion-testing the joints, I noticed lack of tone in Hank’s multifidus muscle on the right.

Typically, when palpating deep lamina groove muscles (rotatores, multifidi, intertransversarii, etc.), I expect to feel ‘knotty’ fibrosis on the side of dysfunction. These are usually the first muscles recruited as the brain’s neuromatrix scans and ‘maps’ the dysfunctional area. If it senses exceptional weakness, it’ll stiffen these short-lever muscles to protect an unstable spine(Fig 4). The burning question is this: Does joint blockage or ligamentous damage always result in deep intrinsic muscle hypertonia (fibrosis) or, as in Hank’s case, can the tissue sometimes become hypotonic or inhibited? Contrary to what I was taught in Philip Greenman’s osteopathic model3, secondary muscle changes in the deep groove muscles from joint blockage do not always result in hypertonicity or spasm. In fact, Dr. Stuart McGill found that when a lumbar facet joint became displaced during a lifting incident, the multifidus on the side of the fixated facets began to atrophy within 24 hours4(Fig 5).

Calling in the Subs

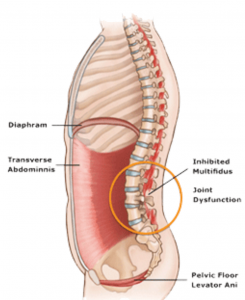

When the brain senses weakness or injury in osteoligamentous tissues, it calls for help from middle layer (core) stabilizers such as the QL, psoas, transverse abdominis, etc. Regrettably, this middle layer postural support system is best designed for lumbopelvic bracing to allow global (extrinsic) muscles and fascia to carry out normal movements of daily living…not for facet joint stabilization. Therefore, when the middle layer is recruited to “sub” for fixated facets or damaged spinal ligaments, firing order patterns are skewed, motor recruitment is garbled, and coordinated movement suffers. Bottom line: Prolonged joint damage can set the stage for aberrant posturo-movement patterns which, in time, causes the brain, through the process of sensitization, to re-map and re-learn the dysfunctional movement as normal (neuroplasticity).

Due to our population’s general lack of proper core support and our inability (through lack of good functional movement training) to adequately activate the middle layers, many, like Hank, find it hard to “hold on” until ligaments heal, fixated facets are released and myo-mechanics are corrected. Sadly, when the oxygen-burning middle layer muscles run out of gas, the load falls back to the damaged joint capsules, spinal ligaments and articular facets which further intensify the pain-spasm-pain cycle.

Regardless of the reason for loss of joint play, when vertebrae are not free to move, muscles assigned the job of moving them (prime movers) cannot carry out their duties and are substituted by synergistic stabilizers, i.e., the brain sends in the subs when a key player is injured. The final stage of dysfunction occurs when the middle and deep spinal layers both collapse causing the load to shift to global (outer layer) dynamic muscles such as the erectors, obliques and lats. These fast-twitch muscles burn glucose and are designed to provide bursts of energy. Spasm develops when they’re forced to act both as movers and stabilizers. As they tire and tighten, the lubricating fluid between fascial bags begins to dehydrate and the facial envelops adhere to neighboring structures often resulting in a big ‘wad’ of hypertrophied erector spinae tissue that therapists beat on session-after-session.

Summary

Once ligaments and joint capsules have healed, manual therapists can help maintain flexibility by elongating cross-linked collagen fibers in the joint capsules and balancing the middle and outer musculo-fascial tissue layers. Myoskeletal articular stretching techniques designed to minimize the accumulation of nociceptive tissue irritants at the injured site help normalize afferent messages to the brain; thus reducing protective muscle guarding around the dysfunctional joint. Once pain-free movement is established, functional movement training effectively restores motor control patterns and allows the brain to reestablish optimal posturo-movement patterns.

References

- Spring Systems

- John Wayne idea from Til Luchau’s John Wayne meets Marilyn Monroe chapter in my soon to be released “Dynamic Body” book.

- Greenman, P., Principles of Manual Medicine, 3nd Ed, pg. 63, Williams & Wilkins, 2003

- Cholewicki J, McGill SM, Mechanical stability of the in vivo lumbar spine: implications for injury and chronic low back pain, Clinical Biomechanics 1996

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.