The label “shoulder complex” appropriately describes the complexities encountered when dealing with pain in this commonly dysfunctional area. Comprised of three joints and one primary articulation, the bones are moved by a complex array of twenty muscles that when functioning properly; permit the greatest mobility of any joint in the human body. The three primary muscles supporting the shoulder complex are pectoralis minor, subclavius, and teres minor — but don’t let the names fool you. They are neither substandard nor minor in their effects on the shoulder. Clearly, these pivot muscles set the position of the shoulder so that larger muscles with greater leverage such as the lats, traps, pects, and delts can perform gross movement of the shoulder and arm. However, when underlying core pivot muscles spasm, form fascial contractures, or become too lax, compensations occur which create muscle imbalances and strain patterns that compress and torsion associated joints. The resulting tissue damage results in increased protective muscle guarding and the formation of neurologic pain/spasm/pain cycles. This ultimately leads to a wide array of shoulder problems, the exact nature of which depends on each individual’s patterns of use.

Running parallel to the collarbone from the first rib, the primary purpose of subclavius appears to be stabilization of the loose-fitting sternoclavicular joint, although most texts refer to it as a depressor of the clavicle. It is important that therapists not underestimate the importance of these small stabilizing pivot muscles. Their duties are less about the movements they create than the movements they prevent. For example, when subclavius contracts its stabilizing effect not only prevents dislocation of the shallow saddle of the sternoclavicular joint, but also limits excessive clavicular elevation. Any micro or macro traumatic event that restricts SC joint range of motion will facilitate or inhibit neighboring muscles causing asymmetrical arm and hand functioning.

Muscle/Joint Mechanics

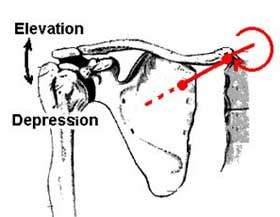

The sternoclavicular joint (SC) provides the only firm attachment for the upper extremity to the axial skeleton. Because it functions as a saddle joint, it can allow for clavicular motion in horizontal abduction/adduction and elevation/depression.

The sternoclavicular joint (SC) provides the only firm attachment for the upper extremity to the axial skeleton. Because it functions as a saddle joint, it can allow for clavicular motion in horizontal abduction/adduction and elevation/depression.

Recall that the SC joint always moves in opposing directions to the scapula. Therefore, shrugging of the shoulders should cause the medial heads of the clavicle to drop down. This configuration produces proximal clavicular depression during arm elevation. So to test, the therapist simply places her fingers on top of the medial clavicular heads and asks the client to shoulder-shrug. If one side does not drop down, there is restriction in the surrounding myoskeletal tissues (muscle, ligament, fascia, disc, or bone).

Clavicular elevation and depression occur around the joints A-P axis

The joint’s AP axis is a line that connects two points (indicated on the figure by filled circles):

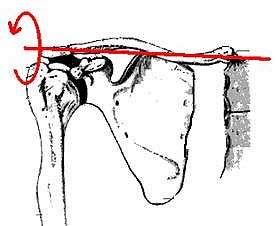

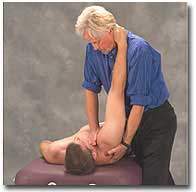

The second and most common restriction seen at this very mobile joint occurs during horizontal flexion of the shoulders. To test, the therapist stands on the client’s right side with the left hand on the client’s back and places his right thumb and index finger on the anterior surface of the medial clavicles (tall people should be seated when performing these assessments). With the index finger and thumb monitoring the anterior clavicular surfaces, the client is instructed to lift arms to 90 degrees and reach forward causing horizontal flexion of the shoulder girdle. The therapist’s finger and thumb should palpate the medial heads translating posteriorly during this maneuver. If one or both sides do not move back, the restriction can alter range of motion in the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints.

Clavical protraction and retraction occur around the joint’s vertical axis

The joint’s AP axis is a line that connects two points (indicated on the figure by filled circles):

The second and most common restriction seen at this very mobile joint occurs during horizontal flexion of the shoulders. To test, the therapist stands on the client’s right side with the left hand on the client’s back and places his right thumb and index finger on the anterior surface of the medial clavicles (tall people should be seated when performing these assessments). With the index finger and thumb monitoring the anterior clavicular surfaces, the client is instructed to lift arms to 90 degrees and reach forward causing horizontal flexion of the shoulder girdle. The therapist’s finger and thumb should palpate the medial heads translating posteriorly during this maneuver. If one or both sides do not move back, the restriction can alter range of motion in the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.