Adding Nerve and Joint Gliding Routines

Addressing Lunate-Triquetrum-Scaphoid Mobility

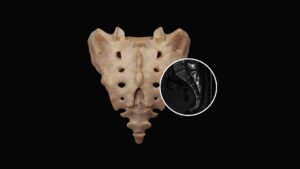

Of the eight carpal bones, the lunate is notoriously the most problematic. It’s prone to sticking (Image 2.), and researchers have discovered that during falls or motor vehicle accidents with the hand outstretched, the lunate can dislocate, compress the flexor tendons, and occlude the median nerve.2 Several orthopedic tests are beneficial in identifying motion-restricted wrist and hand joints, but let’s focus on a single neurological exam I’ve found effective.

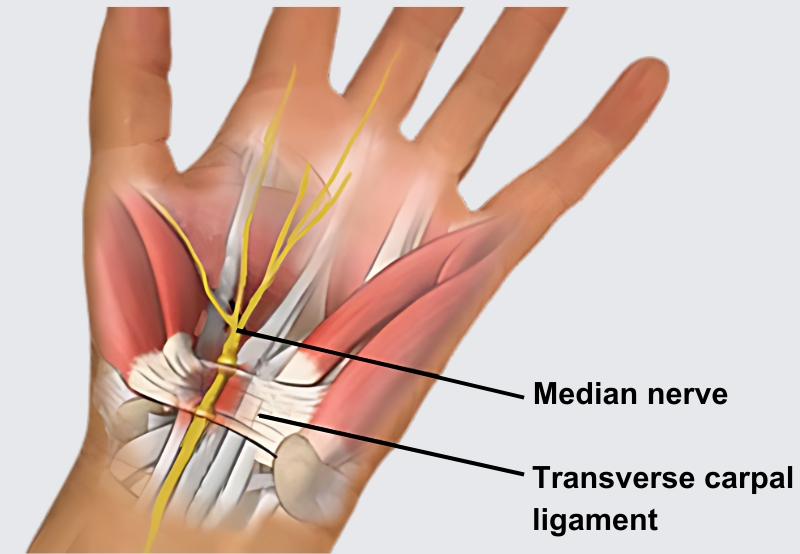

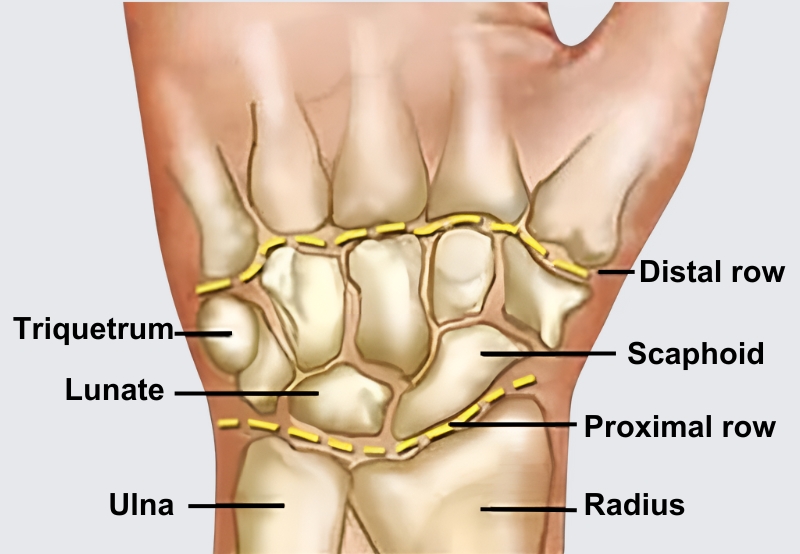

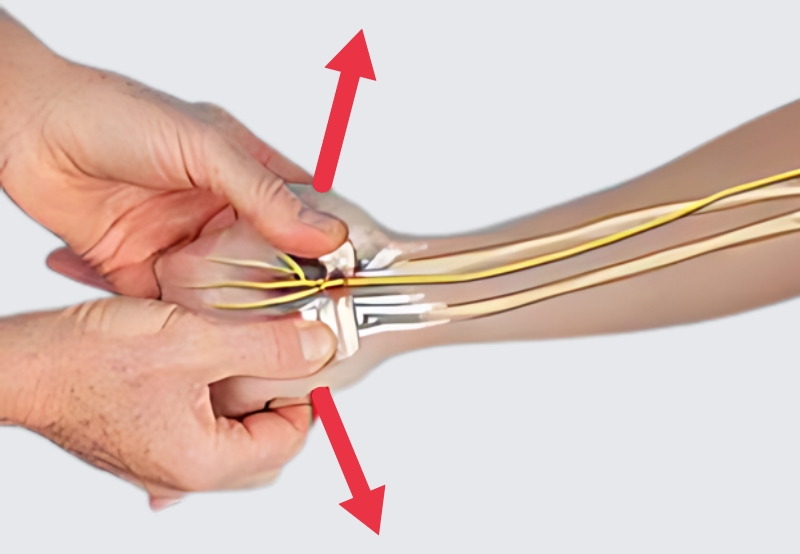

To begin, ask the client to touch the tip of the fourth digit to the thumb and hold firmly, as you moderately attempt to pull these fingers apart, testing the non-affected hand first. Weakness in the ring finger’s opposition to the thumb usually indicates a triquetrum-lunate fixation. Conversely, weakness when testing the third digit’s opposition to the thumb incriminates the lunate-scaphoid joint. The osteoligamentous stretches shown in Image 3. and Image 4. are designed to correct lunate fixations. I encourage you to add these stretches to your current CTS repertoire.

With the client’s elbow and wrist slightly flexed (palm up), the fingers of therapist and client interlace. The therapist’s thumbs glide superiorly until they bump into the radius and ulna bones, and move slightly medially to contact the triquetrum and scaphoid. Holding mild sustained pressure, the client palmar-flexes the wrist against the therapist’s resistance to a count of five and then relaxes. The therapist gently extends the client’s wrist while his thumbs spread the triquetrum and scaphoid laterally to open the tunnel and drag the lunate away from the median nerve. Repeat 3–5 times. (Image 3.)

To create space between the proximal carpal row and the radius/ulna, the therapist extends and gently tractions the elbow and wrist up to, but not entering, the painful barrier. With the therapist’s thumbs positioned on the proximal carpal row, the client slowly palmar-flexes the wrist against the therapist’s resistance to a count of five, and then relaxes. The therapist’s fingers extend the wrist and traction the arm with the intent of spreading the tunnel, gliding the carpals free of the radius/ulna, and stretching the median nerve. Repeat 3–5 times, and then retest the ability of the third and fourth digits to oppose the thumb. (Image 4.)

Restoring CTS Nerve Glide

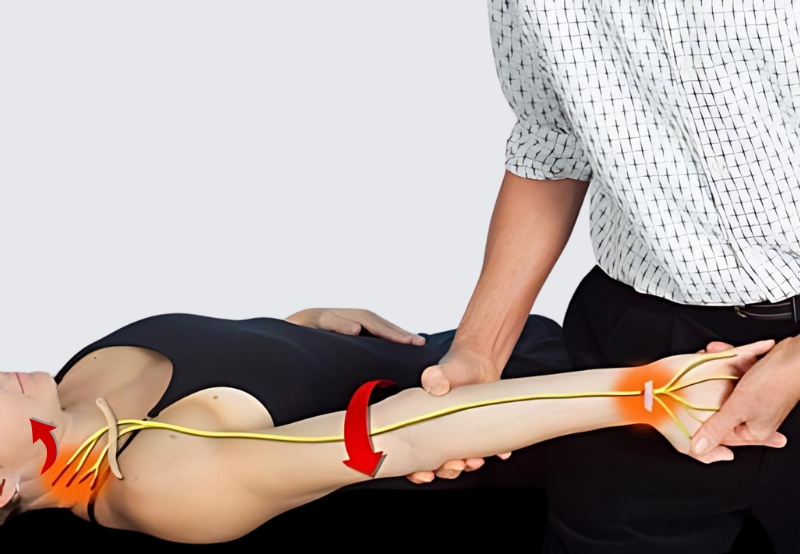

When swollen tendon sheaths and fixated carpals crowd out the median nerve, loss of axoplasmic nutrient flow can trigger chronic inflammation, as well as pain, if the brain feels the injury is a functional threat. A variety of active and passive neural glide techniques exist to help clients with CTS pain, but the flossing routine shown in Image 5. is my favorite. When performing this neurodynamic maneuver, the order of joint positioning is crucial. Begin by stabilizing the shoulder (scapula), followed by the forearm, wrist, fingers, and elbow.

The therapist abducts and externally rotates the client’s arm to 90/90 position. The client is asked to depress and retract her scapula and hold it there. The therapist supinates the client’s arm and extends the fingers and wrist. The therapist slowly begins to extend the client’s elbow until discomfort occurs. The client left sidebends her head as the therapist adducts her arm to reduce stretch off the nerve. As she brings her head back to neutral, the therapist again extends and externally rotates her arm, wrist, fingers, and elbow. Slowly repeat the back-and-forth nerve flossing until symptoms improve.

In this order, each joint-positioning component is added until mild pain is provoked. Therapeutic nerve flossing occurs as the therapist slowly releases the client’s elbow extension (slackening the nerve) while the client sidebends her head to the opposite side (tractioning the nerve). As the routine is repeated, the client’s head returns to neutral (slackening the nerve) while the therapist extends the elbow to stretch the nerve back through the tunnel. Play with this maneuver until you determine the best angle for maximum tractioning.

Summary

Nerve and carpal mobilizations form a powerful team for treating CTS pain. Improved signal conduction to the muscles, increased sensory perception, and greater hand function are just a few of the therapeutic benefits derived from these stretching modalities. Remember to be very gentle when working in areas of nerve inflammation. If your state laws allow, advise your clients how to perform these simple nerve and carpal gliding techniques at home.

References

- C. Fernández-de-Las Peñas et al., “Manual Physical Therapy Versus Surgery for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Randomized Parallel-Group Trial,” The Journal of Pain 16, no. 11 (November 2015): 1087–94.

Eren Cansü et al., “Neglected Lunate Dislocation Presenting as Carpal Tunnel Syndrome,” Case Reports in Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery 2, no. 1 (January 2015): 22–24, doi:10.3109/23320885.2014.993397.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Dalton Technique Tour course!

NEW! USB enhanced video format

Discover deep tissue, pin and stretch, nerve mobilization, and graded exposure stretches in this comprehensive “technique only” program. Upon completion, you will receive 16CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office. Save 25% this week only. Offer expires Monday, January 19th. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course.

BONUS: Order the home study version and get access to the eCourse for free!