Football season is kicking into high gear and soon we’ll begin seeing clients as young as middle school coming in complaining of knee pain. Despite the countless hours of dedicated training, it literally takes milliseconds for an injury to sideline a player, sometimes for the rest of the season. Given the size and speed of athletes today, it should come at no surprise that football has the highest rate of knee injury of any other American sport (Fig. 1). So to rule out serious conditions that may require an orthopedic workup, we’ll review three traumatically-induced knee injuries termed the “Terrible Triad” and then focus our attention on the most common and most treatable of the bunch…meniscus tears. But before we begin, let’s review meniscus anatomy to better understand how this tough cartilage gets injured.

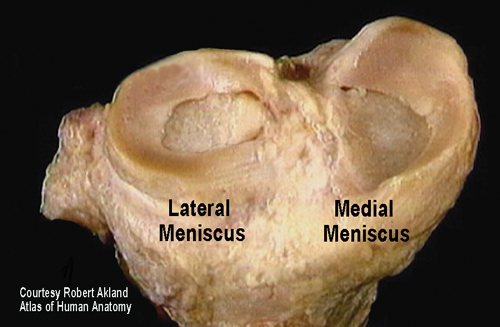

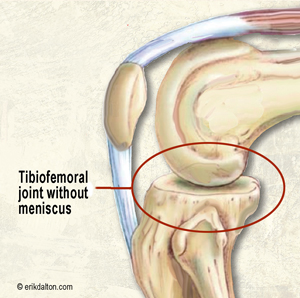

The thick rubbery meniscal cartilage includes medial and lateral compartments located between the tibia and femur bones. Together they are referred to as menisci. The menisci are wedge shaped, being thinner toward the center of the knee and thicker toward the outside (Fig. 2). Functionally, these odd C-shaped structures are critically important for improving load transference. Since the knee is composed of a round femur sitting on a relatively flat tibia, without the menisci, the area of contact force between these two bones would be somewhat small and unstable (Fig 3). When healthy, the paired medial and lateral menisci provide a great deal of shock absorption, lubrication and joint stability to the actively engaged knee.

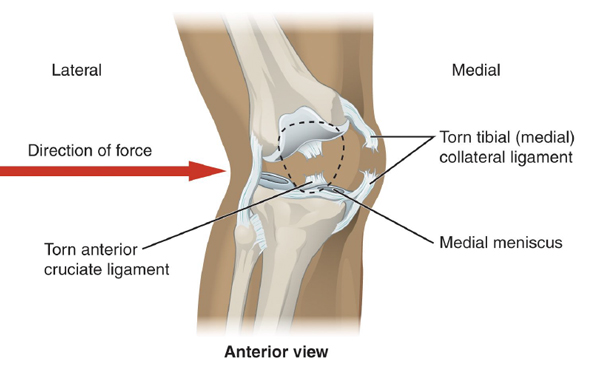

And there’s some good news for manual therapist attempting to mobilize and/or stabilize a knee suffering a meniscal tear. Although the meniscus generally speaking has a very poor blood supply, the outer third is vascularized allowing a greater chance for healing of small acute longitudinal tears. The medial meniscus is more often damaged than its lateral counterpart and during a traumatic football accident, the menisci, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), and medial collateral ligament (MCL) may all suffer serious injury. In sports circles, this season-ending condition is known as the “terrible triad”(Fig. 4).

Modified McMurray, Apley’s Compression & Joint Line Provocation Tests

It’s important to note that most orthopedic tests typically have low inter-tester reliability when performed singly. Yet, when the following three tests are combined, their sensitivity rating (tells if the testing maneuver accurately identified the injured tissues) and specificity rating (tells if the test successfully ruled out the suspected tissue), scores improve dramatically — especially with the addition of a thorough clinical background history.

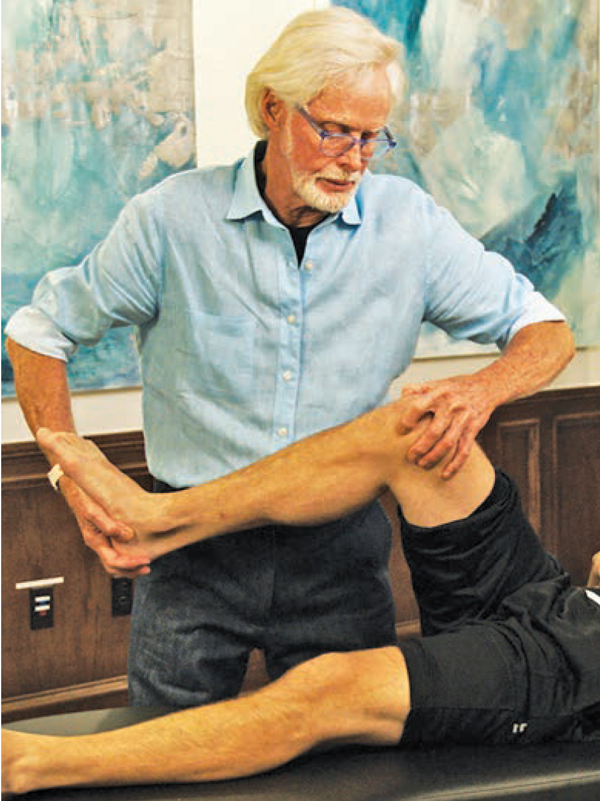

The Modified McMurray is a pain provocation test that helps determine if either the lateral or medial meniscus is at risk. Notice how the hip and knee are flexed at 90-90 with my left thumb palpating the lateral meniscus and my index finger on the medial meniscus at the tibiofemoral joint line. As my hands slowly take the tibia from a position of abduction and external rotation to adduction and internal rotation (valgus position), if the client reports discomfort or clicking along the lateral meniscal border, I make note that the McMurray is positive on that side (Fig. 5). Conversely, if the pain occurs as I bring the knee into abduction and external rotation (varus position) and the client reports discomfort or clicking laterally, he is a positive for possible medial meniscus damage.

The Apley Compression Test shown Fig. 6 in evaluated with the client prone. A positive test result is the production of deep pain or joint line tenderness when the client’s tibia is internally and externally rotated under moderate compression. If the client complains of discomfort during internal tibial rotation, the test is positive for medial meniscus damage and vice-versa.

In the Joint Line Pain Provocation Test (Fig. 7), the prone client’s knee and hip are flexed to 90-90 with the client’s left ankle resting on my right shoulder. To test both menisci at the same time, my thumbs compress the tibiofemoral joint line bilaterally while the client’s knee is slowly flexed. If the client reports tenderness on the lateral side during knee flexion and thumb compression, the Joint Line Pain Provocation Test is positive laterally and vice-versa.

Summary:

During your intake evaluation, take time to look above and below the pain site while examining the system as a whole. As Gray Cook says: “Treat the pattern…not the pain.” Manual therapy, alongside a well-designed and executed corrective exercise program, will help keep your clients in the game. Ultimately, this treatment combo will improve movement pattern dysfunction, and permit optimal functioning of the body’s natural healing processes.

Techniques as demonstrated in Essential MAT Assessments Course

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.