Manual therapists often shy away from treating scoliotic clients, and for good reason. In the absence of a basic understanding of spinal biomechanics, soft tissue work may not produce the desired results and treatments that are too “heavy-handed” may even exacerbate the client’s condition. Yet, one thing I’ve noticed in many years working with scoliotics is this: There is always a functional (fixable) component to every structural (fixed) scoliosis.

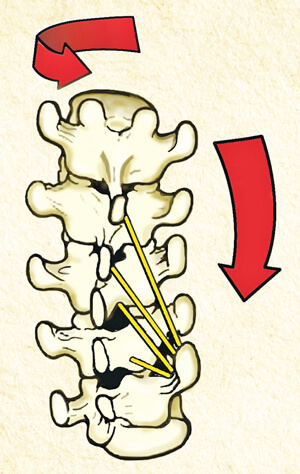

The simplest way to ‘weed-out’ functional from structural dysfunctions is with the Adams test. Stand behind the client and ask her to slowly forward bend with relaxed arms hanging freely. Keeping your eyes in line with the client’s back, carefully observe for any changes in shape of the thoracic and lumbar spines (Fig. 1). Compared to the standing position, does the convex hump change, get worse, or diminish? If the curve stays the same or gets worse, some of the vertebral joints (and possibly ribs) are fused. To confirm your visual observations, ask the client to slowly sidebend and rotate her torso allowing the arms and head to gently swing side to side. During these maneuvers, if any vertebral segments of the convex hump become more symmetrical, they are not yet fixed and should be addressed. Osteopathic physicians have named this condition, where three or more adjoining vertebrae become fixated sidebent to one side and rotated to the other, a Type 1 group curve (Fig, 2).

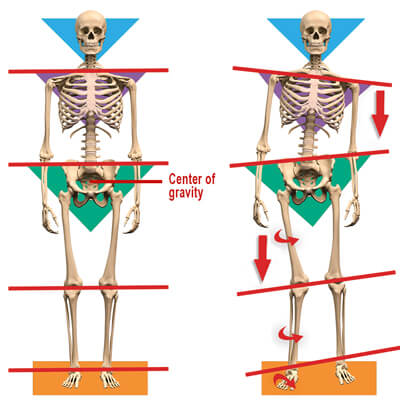

According to my mentor, the late Philip Greenman, DO, “A functional scoliosis is a postural adaptation to an imbalance in one’s base of support.” Most of us think of the feet as our only base of support, but what about the sacral base and occipitoatlantal joints? When unlevel, the brain’s vestibular and visual systems must make necessary adjustments via head-righting and postural reflexes. Prolonged imbalances in these bases of support may trigger ascending or descending postural compensations via protective muscle spasm. We now know there is asymmetry in muscle function for everyone with scoliosis. More specifically, there is uneven strength in trunk rotation. This asymmetry affects one’s posture, appearance, pain tolerance, and in more severe cases, the ability of one’s lungs to function to their full capacity. (Fig. 3).

Because scoliosis is a three-dimensional problem, always look for patterns. For example, when observing the standing client from the front, notice how one shoulder is lower than the other. Look for oblique crossing patterns traversing from the external obliques and pectoral fascia to the contralateral hip. Use any of your favorite myofascial and graded exposure stretching techniques to unwind these neurologically driven patterns.

Scoliotic clients will always present with length-strength muscle imbalances. The resulting asymmetry is thought to affect posture, appearance, pain tolerance and, in more severe cases, the ability of the lungs to function to their full capacity.

Improved technology and the ability to assess muscle function have changed the picture in regards to the benefits of exercise for scoliosis. We now know there is asymmetry in muscle function for everyone with scoliosis. More specifically, there is uneven strength in trunk rotation. Proprioceptive exercises such as wobble boards and balance-ball training improves body positional awareness, and is particularly beneficial for scoliotic clients. Pilates, Yoga and Tai Chi also challenge spinal stability/mobility, and are great motor learning exercises that stimulate nervous system functioning.

Myoskeletal Alignment combined with proprioceptive exercise may help improve ingrained motor control problems and sensory motor amnesia in those with functional or structural scoliosis. Beyond this, specific brain-based corrective exercises such those in Paul Kelly’s new Physiokinetix Training program, may also be beneficial in establishing proper length/strength balance and spinal stability.

Texas Twister Technique

GOAL: Reduce excessive kyphosis on client’s scoliotic hump

LANDMARK: Thoracic spine and ribcage

ACTION:

- With client prone, therapist’s right hand contacts client’s right thoracic spine and his left braces the left

- Twenty to thirty pounds of pressure is applied to the spine and ribcage to take out the slack

- Next, the therapist’s hands gently apply a springing maneuver in opposing directions to test areas that resist extension

- Therapist then twists the tissue in various directions searching for and relieving restrictions

- Repeat several times on each side

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.