Video from Upper Body Home-Study

Our brains are very much like sponges. They are malleable and constantly adapting to peripheral input by strengthening existing neural connections and networks, a process called long-term potentiation (LTP). The more we use a particular neural network, the stronger it becomes, as we are reinforcing those brain map connections. For instance, I conclude each myoskeletal session with a routine called closing stretches. In that series of nine techniques, there’s one particularly tricky maneuver that requires focused attention. For years, as I approached this “torso-twist” stretch, I had to specifically remind myself to reach over and grasp client’s right arm and lift the scapula, slide left hand under scapula to elevate, and then lift and twist torso as my left hand pinned the client’s right ASIS (Image 1). One day, I realized I’d completed that complex maneuver without coaching myself through it. The years of practice had finally reinforced those neural circuits, allowing me to perform the skill unconsciously. This is LTP at work and it demonstrates the underlying cellular mechanism of learning and memory.

For years, that tricky closing stretch was a great example of explicit memory, or information we have to consciously work to remember. Eventually, the maneuver moved to implicit memory — information that can be remembered unconsciously and effortlessly. Also called procedural memory, implicit memory is the unconscious memory of skills and how to do things, particularly the use of objects or movements of the body, such as throwing a ball, playing guitar, or massaging a client’s shoulders. This is a functional form of memory that cannot be consciously recalled. Such memories are typically acquired through repetition and practice and are composed of automatic sensorimotor behaviors that are so deeply embedded we are no longer aware of them. Once learned, these “body memories” allow us to carry out ordinary motor actions more or less automatically, i.e., “the hands know more than the head.” The question is how did I move from explicit to implicit memory during that complex closing stretch, and is there a faster way to get there?

Multi-media learning speeds mastery

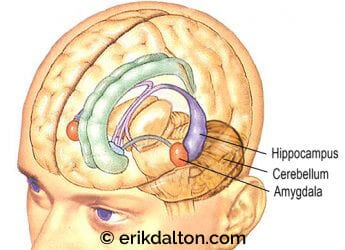

Today’s neuroscientists have discovered that implicit memories are primarily encoded and stored in the cerebellum and motor cortex, both of which are involved in motor control (Image 2), whereas explicit memories are predominately encoded by the hippocampus. For years, scientists erroneously believed all information on a particular subject — whether learned via reading, watching TV, or listening to an audio device — was compiled in a single area of the brain. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan was one of the first to disagree with this theory. In his classic book “Understanding Media,” McLuhan introduced the world to the idea that “the medium is the message.”2 Put simply, the manner in which information is communicated has more of a profound effect on the person receiving the information than the information itself. So, what does that mean for manual and movement therapists?

The takeaway is that tapping a variety of methods to learn and practice one’s skill set may be the fastest road to mastery. In other words, the most efficient way to move information from explicit to implicit memory is through multi-media formats, which include visual, touch, audio, and other sensory inputs. For example, participating in various hands-on workshops and research conferences exposes the brain to diverse viewpoints on the same subject, making learning more fun and engaging, and, therefore, more effective.

To expand your skill set, practice does make perfect, but the process can be speeded along by exposure to a variety of learning mediums, such as books, DVDs, audio recordings, and technique demonstrations from an array of educators. The brain loves novel stimuli, such as playfully practicing techniques while viewing yourself in a mirror or teaching a new routine to a partner. Adding emotion to your sessions through playful practice further stimulates the brain’s amygdala function, causing memories to move more quickly from explicit to implicit. You can’t teach experience — but mastery can be accelerated through proper input.

- McLuhan, Marshall (1964) McGraw-Hill

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.