Treating Neuromuscular Righting Reflexes

Containing the same type of nerve and glial cells, the spinal cord is a direct extension of the brain. And, although researchers have long dismissed René Descartes’ hardwired central nervous system (CNS) model, the spinal cord, in some ways, still resembles a hardwired switchboard and cables (Image 1). As a cable, it connects the brain with the body’s peripheral nerves, and as a switchboard, it coordinates muscle movements and spinal reflexes under its direct control. Optimal positioning of the head, pelvis, and spinal cord enhances nerve impulses and reflexes traveling to and from the brain. By manually leveling the head on the neck and balancing the spinal column on a horizontal sacral base, Myoskeletal Alignment seeks to normalize electrical activity in these righting reflexes.

Head Righting Reflexes (HRR)

The head houses sensory organs (teleceptors) that connect us to the distant world. When floating comfortably atop the spine, cranial teleceptors reflexively orient head placement using light, sound, and gravitational sensory information. However, our brains are often unable to make sense of visual input without movement. The eyes must constantly move (saccades) for light to traverse across the retina, which allows the CNS to construct visual images by comparing adjoining structures in the environment. Teleceptor function is compromised when the head is persistently maintained in an abnormal position. As spastic neck and jaw muscles inflict whole-body reflexive movement constraints, CNS “noise” heightens the body’s stress response.

A catch-22 occurs when a poorly aligned body initiates HRR that trigger spasm and mechanically alter spinal joint movement. When hyperexcited joint and ligament mechanoreceptors initiate protective splinting, some muscles overwork and others are inhibited. This results in reduced mobility, excessive energy consumption, exhaustion, and, if the brain perceives threat, pain.

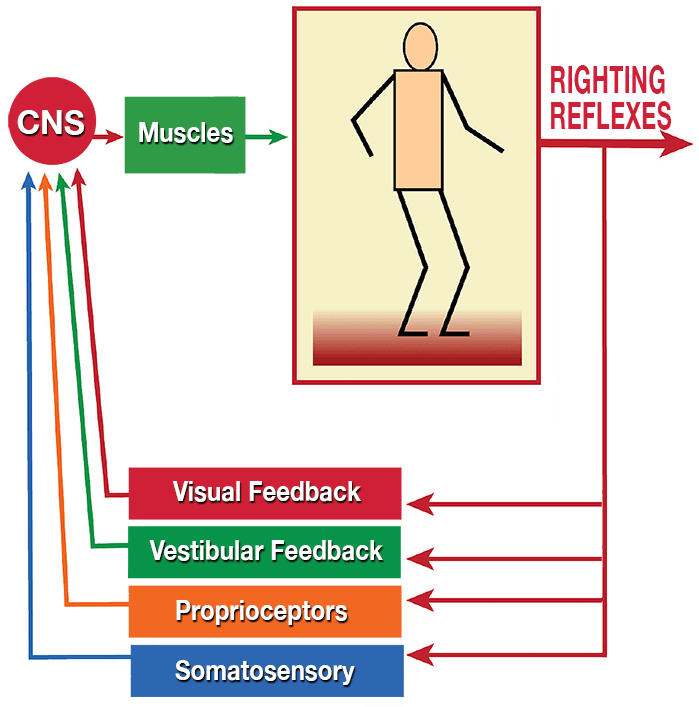

In Image 2., notice how CNS righting reflexes from visual, vestibular, and somatosensory feedback work together to make instantaneous neuromuscular postural adjustments.1 In his classic 1949 book, “Body and Mature Behavior,” Moshe Feldenkrais offered this explanation of righting reflexes: “When the head has been righted and the body held in a lateral position, the neck is twisted. The proprioceptive nerve organs in the neck muscles, joints, and tendons are stimulated and the thorax rights itself so as to untwist the head. The twist is now displaced to the lumbar joints, and the pelvis is righted as well by the proprioceptive stimulation arising from the lumbar region. We see here the neck and lumbar-righting reflexes acting so that the body stands properly and follows the movements of the head.”2

Left Anteriorly Rotated Illium Correction

The therapist braces the client’s hip with his body and extends the right thigh to the extension barrier. The client pulls on the left knee to posteriorly rotate the right illium and level the sacral base. (Image 3.)

Right posteriorly rotated illium correction

The client presses the knee against the therapist’s chest & relaxes. The therapist leans into the leg while pulling on the left posteriorly rotated illium (left leg can hang off the table edge if needed).(Image 4.)

During forward bending and rotational movements, all vertebrae that can participate should do so. Chronic immobilization due to protective guarding shifts excessive strain to the remaining mobile joints, increasing risk of injury by limiting available motion. Well-coordinated HRR rely on an aligned pelvis, springy ribcage, and a cervical spine that’s both flexible and stable. In Images 5 and 6, I demonstrate head-on-neck leveling techniques for relieving suboccipital spasm and accompanying cervicocranial misalignment.

Subocciptal Release

The therapist right side-bends the client’s head as soft finger pads softly drag on lateral suboccipitals. (Image 5.)

Occipitalatlanto (O-A) correction

The client tucks the chin and the therapist applies two seconds of mild overpressure to help align the O-A & level the craniocervical junction. Side-bend the head 20 degrees to the right, then to the left. Repeat.

Clinically, it appears righting reflexes may trigger neck and pelvic muscle spasticity in an a

Clinically, it appears righting reflexes may trigger neck and pelvic muscle spasticity in an attempt to level the eyes against the horizon. Further, if the reflexive spasm alters ilium and sacrum alignment, the CNS may generate ascending syndrome compensations that spiral up the ribcage, shoulders, and neck, forcing further unleveling of the eyes. In Images 3 and 4, I show a couple of favorite iliosacral alignment techniques for leveling the sacral base and relieving reflexive muscle spasm.

MAT techniques as demonstrated in the Motion Is Lotion MAT Course.

Summary

Overall body balance is best achieved by leveling the head and tail during a single therapy session and retesting in subsequent visits. Try to include movement awareness dialog during your hands-on work, such as, “Feel how your low back and hip bones contact the table as you slowly tilt the pelvis forward and back.” Offer immediate feedback if you sense unnecessary effort or rigidity.

Helping clients become aware of inefficient movement patterns is a learning process, not a procedure. Our bodies are shaped by how we use them, and habits determine use. It is the client’s underlying habits that need to change, and we can help. When confronted with pain and injury cases, rather than chasing the pain, first evaluate what the client may be doing to cause the problem, and help them learn how not to do it. Manual and movement therapy can then address abnormal neuromuscular righting reflexes that may be causing protective muscle guarding and accompanying joint dysfunction.

References

1. Goldberg, J.M., Wilson, V.J., Cullen, K.E., Angelaki, D.E., Broussard, D.M., Buttner-Ennever, J., … Minor, L.B. (2012). The vestibular system: A sixth sense. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

2. Feldenkrais, M. (1949). Body and mature behavior: A study of anxiety, sex, gravitation and learning. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.