Peroneal Nerve Mobilization

Tightness is one way the brain applies the parking brake when the body’s natural braking systems fail — and pain is another. When working properly, the brain’s motor control system is finely tuned to process peripheral input and deliver appropriate output. However, when the body’s healing mechanism has been compromised, the nervous system has the ability to fully engage the parking brake to slow us down and keep us out of trouble.

When bodyworkers palpate tissue tightness or scarring from an old injury, we often notice a significant amount of resting tone in neighboring muscles. In these cases, the brain may have ordered the musculofascial tissue to tighten and maintain a significant amount of resting tone to protect a perceived weak link in the system. To most bodyworkers, excessive muscle tone indicates a lack of mobility, but we need to look further to see if it has a specific cause or is simply a tissue “habit” that got stuck on the client’s hard drive and needs to be cleaned. This motor control loss is frequently helped through high-quality bodywork. I’ve found the neurological effects of Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques combined with cognitive reassurance and corrective exercise help boost confidence while restoring optimal functional movement. For example, the client in the photo below (Image 1.) suffered a fairly serious (grade 2) inversion ankle sprain when thrown from a horse eight months earlier. During gait evaluation, I noticed him limping. He said his doc told him the limp had become a habit and would soon go away — but I’ve found that’s not always the case. Granted, a limp was functional for this client after his painful ankle injury because it offloaded stress, allowing him some degree of locomotion. However, it became dysfunctional once the injury had healed and there was no longer a reason to offload stress. The clients lingering limp presented a red flag, telling me we may be dealing with a nervous-system processing problem, sending down faulty commands to continue limping.

Assessing locally, thinking globally

To identify and correct my client’s hip and leg cramping symptoms, I first wanted to determine if the ankle injury was driving the protective muscle guarding I was palpating or if biomechanical compensations from months of limping might be triggering compensatory hip and leg spasm. Initial hands-on assessment of his lower limb revealed limited ankle mobility and peroneus longus and brevis compartmental rigidity. Since these fibularis muscles evert and plantar flex the foot, it’s likely they were either strained during the fall or recruited by the brain to splint and stabilize the inversion sprain. To address the peroneal spasm, I applied a mild sling and resist technique (Image 2.). The therapist’s right hand slings the client’s ankle into eversion and the left hand resists. The goal is to reduce the peroneal muscle spasm and ligamentous ankle adhesions.

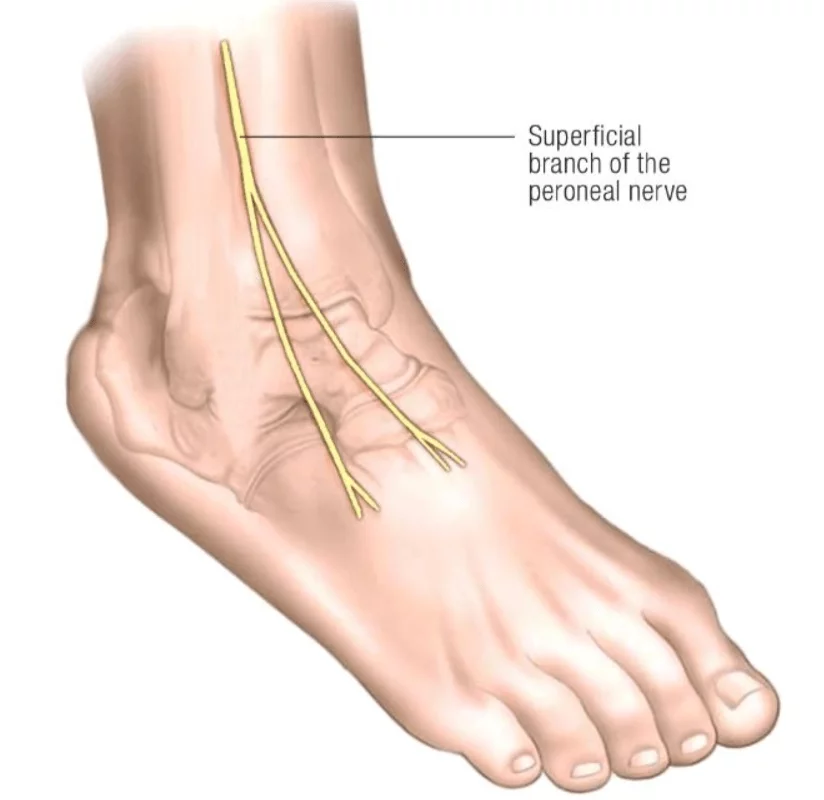

This maneuver seemed to work nicely for creating mobility at the talocalcaneal joint, but when I went to the other side of the therapy table to perform the same technique from a different angle, an unexpected thing happened. As my webbed fingers compressed the tissue overlying the superficial peroneal nerve at the anterolateral aspect of the ankle, he recoiled in pain. Damage to this peroneal branch of the sciatic nerve during an inversion injury is not uncommon and is often misassessed (Image 3.).

To confirm a peroneal traction injury, I performed a supine straight leg sciatic test with the client’s foot dorsiflexed and inverted (Image 4.). He tested positive and also reported mild buttock and lateral thigh pain, indicating possible low back sciatic entrapment.

To floss the peroneal nerve, slowly raise the client’s leg to the first sign of discomfort, as you bring the extended leg down, the client flexes the neck to pull the sciatic nerve headward. Repeat the back and forth flossing movement for two minutes each session, and recommend the client continues to practice the technique at home after the session.

In Myoskeletal Alignment, we’re always looking for compensatory patterns that may be contributing to a client’s motor control problem, but other than a slight iliosacral alignment issue and a limp, he did not present with anything remarkable. I performed an SI joint spring test, hip abduction test, and an Adam’s test — all were negative.

Throughout the next few sessions, I focused on freeing the fibularis adhesions around the lateral malleoli and various peroneal nerve mobilization maneuvers. I supplied him with a TheraBand stretch strap and taught him a couple of sciatic nerve mobilizations to perform between sessions.

To help the brain re-map the motor control problem causing the limp, he was asked to slowly practice walking backwards and sideways with his pelvis tucked for 15 minutes a day, followed by 10 minutes of slow bouncing on his mini trampoline. Novel movement routines such as these help convince the brain the ankle is now fully functional.

Summary

Muscle tightness is often the brain’s way of applying the brakes when it senses loss of coordination, timing, and symmetry due to tension, trauma, or poor posture. This motor control loss is frequently helped through high-quality bodywork. However, for the brain to permanently re-map the new posture or pain-free movement, it must learn new movement patterns. I’ve found the neurological effects of Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques combined with cognitive reassurance and corrective exercise promote confidence and help restore proper movement.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.