Techniques help tackle and prevent shin splint pain

Racewalking (RW) popularity is on the rise as a less-demanding alternative to running. However, unlike some low-impact activities, RW is a difficult skill to master, requiring good technique and fitness to be competitive. Although little RW injury research has been published to date, two survey studies found that race walkers sustained injuries similar to runners.1,2 Not surprisingly, lower leg injuries such as shin splints and ankle sprains topped the list for both groups. This may lead therapists unfamiliar with treating race walkers to wonder how a seeming low-impact sport like RW would produce running-type injuries3. According to my competitive RW clients, the rules of the game are to blame.

The Knees Rule

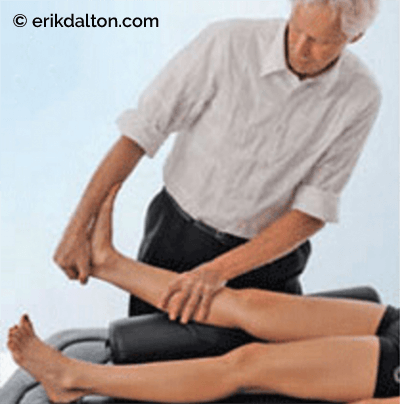

Among these rules, as mandated by the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF), is what is called the Knees Rule 4. This rule dictates that the knee of the supporting leg must straighten from the point of ground contact and remain extended until the body passes directly over it (Image 1). Some believe the athlete’s shin must absorb a force of two to three times his or her body weight during a straight-legged heel strike. This may not necessarily be a problem for well-conditioned professionals, but amateur athletes are another story. In some, the jarring heel strike is followed by an uncoordinated and energy-wasting slap down of the foot, which must be resisted by eccentric contractions of the dorsiflexor shin muscles. Cumulative repetitive dorsiflexor stress and length-strength musculofascial compartment imbalances likely are the two primary causes of shin splints.

Although the tibialis posterior muscle is thought to be the most commonly injured, in many cases the medial portion of the soleus is also involved. Both muscles arise from the tibia and fibula, but because of their different attachment sites, sports therapists tend to blame the soleus if the pain and tenderness manifests on the lower one-third of the tibia.

2). An injury to either muscle can be difficult to manage due to their anatomical locations. Over time, repeated concentric and eccentric loading during heel strike and toe-off strains the attachment sites, creating periosteal micro tearing (periostitis). In an attempt to resist painful pulling at the injury site, the body reinforces with adhesive scar tissue. Greater muscle tightness develops as the athlete tries to train through the injury, resulting in a vicious cycle of pain and tightness that continues until the area is properly treated and retrained. In Image 3, I demonstrate one of my favorite techniques for shin splints, breaking loose stiff cross-linked scar tissue adhesions along the medial tibial border.

Loss of Contact Rule

Another IAAF regulation requires competitive race walkers to keep the back toe on the ground until the heel of the front foot has touched. This rule also sets the stage for shin splint injuries as the athlete strains to keep the back foot in the push-off position until heel strike.

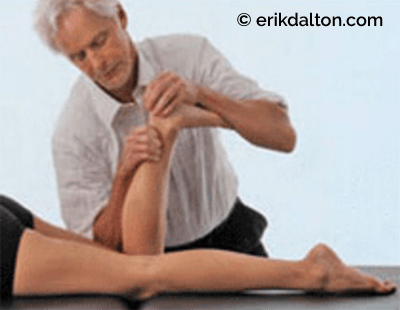

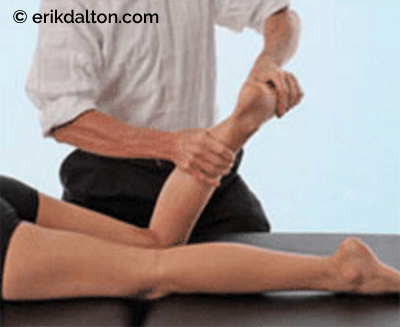

The gastroc, soleus, and tibialis posterior muscles must forcefully contract during this maneuver, which, in time, creates reciprocal weakness in the peroneals and tibialis anterior muscles. Many of my competitive RW clients schedule bimonthly preventative maintenance appointments to help retain lower leg muscle balance. In Image 4, I demonstrate an effective technique for stretching tight posterior calves and restoring ankle mobility, and in Image 5, a spindle-stim muscle activating technique helps turn on weak anterior compartment muscles such as tibialis and peroneus. Additionally, a variety of balancing, band-work, single-leg squat, and mobility exercises are offered as homework to help maintain length-strength balance and ward off shin splints, compartment syndromes, stress fractures, and other common walking and running injuries.

Note: When palpating the tibia, if tapping on one small spot triggers exquisitely sharp pain, or if the athlete is experiencing overall numbness or unusual nerve sensations, a medical referral may be necessary to rule out stress fractures or compartment syndromes.

References

- Kummant I. Racewalking gains new popularity. Physician and Sportsmedicine;9(1):19-20

- Payne AH. A comparison of the ground reaction forces in race walking with those in normal walking and running. In: Asmussen E, Jorgensen K, eds. Biomechanics VI-A

- Palamarchuk R. Racewalking: a not an injury free sport. Sports Medicine ’80

- Competition Rules 2012-13. In: [IAAF] IAoAF, ed Vol 230.1. Monte Carlo: IAAF; 2011

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.