Treating the TMJ

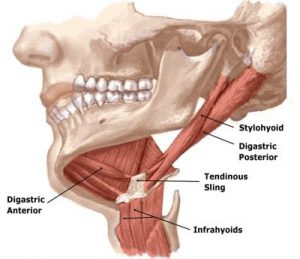

It’s not uncommon to be in the final stages of a history intake when the client casually states, “Oh, there is one other thing — sometimes my jaw clicks when I eat or open my mouth”. A clicking jaw in those presenting with face, head and neck pain may be a smoldering fire that should not be ignored. Joint noise is not unusual, but a clicking jaw can represent an incorrect condyle-disc-mandibular fossa relationship or possibly osteoarthritis (Image 1).

I find it’s best to address jaw-related muscle imbalance patterns before the disc(s) becomes irreversibly deformed. A systematic review by Medlicott and Harris found that active exercise, manual mobilizations and postural training may be effective in treating temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders.1 However, many therapists choose not to treat the condition unless the client is experiencing pain. I believe this represents a missed opportunity to address anatomical and functional problems in their early stages.

When the head and neck move forward in the sagittal plane, the brain’s visual proprioceptors cause the occiput to backward-bend on atlas. This remarkable brain stem reflex (Law of Righting) will cock the head back to level the eyes against the horizon even if it means ravaging the neck.

Sustained isometric contraction in the suboccipitals reflexively weakens the longus capitis and colli antagonist muscles and places the entire nervous system in a heightened state of alert. With the head and neck jutted forward, passive tensile forces develop in the hyoid and digastric muscles (Image 2).

The brain, in essence, is trying to compensate for the forward head carriage by pulling back on the cranium using the jaw muscles. Prolonged hypercontraction in these jaw openers stresses the TM joint as the mandible is forced to translate posteriorly and inferiorly…a condition called jaw retrusion.

This may be problematic since the hyoids, digastrics, and the lateral pterygoids are jaw openers and the brain doesn’t like us to walk around with the jaw hung open. So, the only recourse the brain has now is to call on powerful jaw closers such as the temporalis, masseter and medial pterygoid muscles.

Thus, the battle begins and the mouth closers usually win, but at a terrible cost to the TM joint and neck. Antagonistic co-contraction of these muscle groups may promote abnormal mandibular positioning, nerve entrapment, ligamentous strain, and disc compression, leading to the TMJD disorders we commonly see in our massage and bodywork practices.

In Myoskeletal Therapy, we begin by creating a level platform at the occipitoatlantal (O-A) joint and then perform a basic TMJ routine such as the one shown in this video. Home retraining exercises such as the “chin-tuck” is suggested to help reinforce the work.

Treating TMJ Pain – step-by-step instructions

GOAL: Decompress mandible from condyle

LANDMARK: Masseter, temporals and mandible

ACTION: (Client Supine)

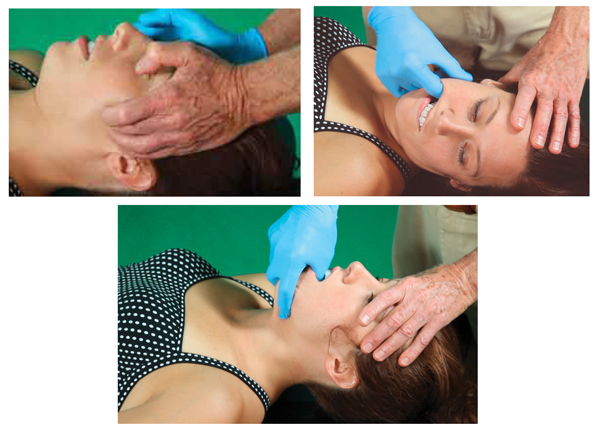

- With client lying supine and therapist standing at head of table, therapist’s flat soft fingers palpate client’s masseter muscles searching for areas of tightness and/or tenderness.

- The therapist moves up to the temporalis muscles and repeats the flat finger technique.

- The client is asked to slowly open and close her mouth to help therapist release restrictions above and below zygomatic arch.

- Once the external musculofascial tightness has been addressed, the therapist places a disposable medical exam glove on his right hand.

- The therapist asks the client to open and close jaw as he observes for uneven movements such as “jaw-jutting” to one side.

- The therapist places his left hand on the client’s forehead, his thumb on the mandible under the lower front teeth, and his fingers gently grasping client’s chin.

- As the therapist steps to his left foot, a gentle pressure braces client’s forehead and the jaw is slowly and gently pulled out and up to the first restrictive barrier.

Note: Practice this technique under professional supervision. Always ask the client’s permission and in your history intake, make sure the client has had no: jaw surgeries, bridges, plates, or chronic TMJ problems. This technique is helpful for decompressing the muscles that bind the jaw closed (night grinding, jaw retrusion, etc.), or conditions that cause uneven opening and closing.

- Medlicott M.S., & Harris S.R. (2006). A systematic review of the effectiveness of exercise, manual therapy, relaxation training and biofeedback in the management of temporomandibular disorder. Phys Ther, 86(7), 955–973.

Why I created Technique Tour…

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.