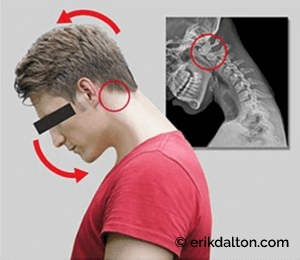

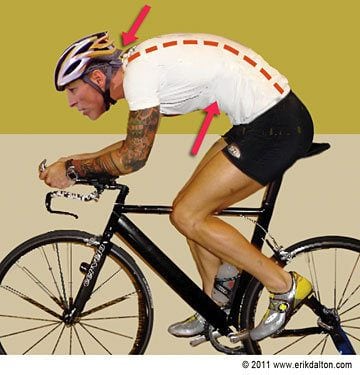

Summary: Like many of our popular, but abnormal, athletic endeavors such as golf, tennis, bowling, etc., cyclists bring with them a complex biomechanical downside that is frequently hard to completely fix. The “arched back” model is typically the most problematic. In an effort to level the eyes, the rider must hyperextend occiput on atlas. The cervicothoracic junction is also forced to hyperextend (neck-on-shoulders) resulting in chronically locked intervertebral joints and rib jamming.

It is incredible the money and time many elite and “weekend-warrior” cyclists devote to retrofitting racing bikes to conform to their bodies rather than first restoring function to the most critical piece of racing equipment: the body of the rider.

When muscle imbalances, faulty movement patterns, and joint fixations distort the bony framework of the body, the cyclist is led on a never-ending journey searching for that perfect bike fit.

My personal mantra: “Fit the body to the bike, stupid!”

Bodyworkers and functional movement trainers whose practices cater to amateur and elite cyclists are highly aware of the clinical and performance advantages gained by restoring optimal mobility, flexibility, and stability to the muscle/joint complex. It makes sense to first get the kinks out before sending the client off for an expensive and sometimes useless bike retrofit. Without hands-on maintenance and functional fine-tuning, they often unknowingly reinforce dysfunctional movement patterns ingrained from long-forgotten micro- or macro-traumatic injuries.

Bewilderment and controversy over this chicken-or-egg (bike-or-body) thing is primarily due to lack of understanding of the Law of Cause and Effect. For instance, let us say a bike shop performs a retrofit and Bob, the cyclist, smilingly pedals away on his newly reconstructed bike feeling secure and pain-free – Life is good… or is it?

Unfortunately, if Bob is one of many “flexion-addicted” Americans with a sedentary job that keeps him glued to the computer terminal day-after-day, gravitational exposure will gradually drag his body into a big “C” curve. In time, Bobs brain relearns this aberrant posture as normal and on weekend expeditions his “hip-flexed” desk posture morphs into a similarly distorted riding posture.

To make matters worse, stubborn pain-spasm-pain cycles often appear as the hip stiffens and the imposed stress destabilizes sacroiliac and low back structures. In the presence of lumbar spine instability, the brain may decide to lock down the low back and ribcage with protective muscle guarding. Thoracic cage rigidity not only inhibits proper diaphragmatic breathing but also sends shock waves through the thoracolumbar and pectoral fascia and into the upper extremity joints where reverberations are met with strong resistance from habitually locked hands, elbows and arms. Meantime, compensations from adhesive hip capsules also travel down through the knees, ankles, and feet searching for a weak link in the lower kinetic chain.

Cyclists who go for a bike retrofit prior to receiving manual therapy to release fibrotic hip capsules and hip flexors, soon notice a loss of endurance and may develop soft tissue or joint sprains associated with lumbopelvic imbalance. Strangely, many flexion-addicted cyclists attempt to work through the injury despite sensing a noticeable reduction of speed, power, and efficiency. “No pain, no gain” is an unacceptable working model for those pursuing longevity in the cycling sport.

Does decreased hip angle mean less power?

One of the most common cycling positions used by “flexiholics” has the hip flexors locked short and the hams and glutes overstretched and weak. This imbalance pattern as described by Vladimir Janda in his lower crossed syndrome, forces the pelvic bowl to be drawn too far forward resulting in a decrease in hip angle.

Those who consistently ride with an anteriorly rotated pelvis and decreased hip angle are subject to capsular and ligamentous adhesions and a subsequent loss of economy and power. To accommodate the loss of hip extension, many recreational and competitive racers compensate by posteriorly tilting their pelvic bowl and rounding their backs into a hyperkyphotic posture just to advance hip angle and power. The famed cyclist Andy Pruitt believes that changing the seat height by a mere inch alters mechanics and motor control patterns of every joint in the lower extremity. By reducing seat height, excessive force is transferred to the patellofemoral joint, while raising the saddle too much strains the hamstrings, low back, and hands…

Erik Dalton, Ph.D., Certified Advanced Rolfer, founded the Freedom From Pain Institute and created Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques to share his passion for massage, Rolfing, and manipulative osteopathy. Visit the Erik Dalton website for information on workshops, conferences, and CE home study courses.

Read More ~ http://erikdalton.com/media/published-articles/bike-body/

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.