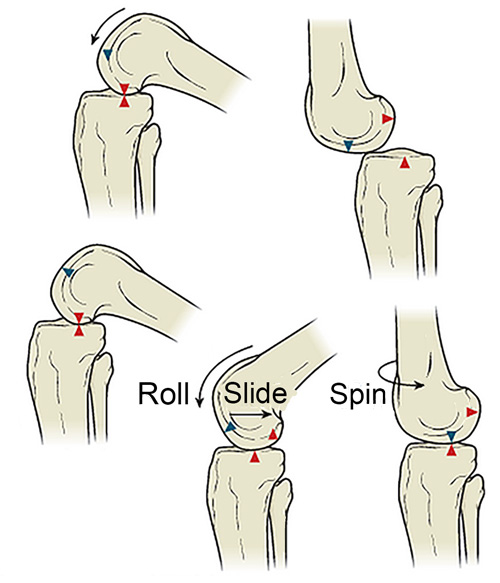

Everything designed to move has a built-in factor of “play” to promote efficient functional movement. For example, an automobile piston and cylinder, a wheel on an axle, and even a simple hinge all have calculated play between their moving parts to allow efficiency of movement. Why not in a human joint? (Image 1.)

In 1964, John Mennell, MD attempted to answer this question in his book “Joint Pain: Diagnosis and Treatment Using Manipulative Techniques.” Since its introduction, this valuable time-tested joint play principle has yet to be expanded on, however in today’s age of evidence-based medicine, research is still sorely lacking. To better understand the concept of joint play, joint dysfunction first needs to be defined. According to Mennell, joint dysfunction is the loss of joint play movement that cannot be recovered by the action of voluntary muscles. This condition is readily reversible in its early stages, but cannot be demonstrated after death, which presents a difficulty in researching his joint play concept.

Mennell defined joint play as small movements that are independent of voluntary muscle contraction. Measuring less than 1/8 inch in any plane, these movements provide roll, glide, spin, and distraction combinations to aid in smooth joint motion. Capsular laxity allows for this joint gliding motion and is essential for producing optimal active and passive ranges of motion. Mennell stressed the neurological importance of these small involuntary movements, as their integrity greatly affects the performance of the gross voluntary movements of synovial joints. Further, he believed that movement was not primarily governed by muscle function, since muscles are “unable to move joints which are not free to move.”

In our traditional teaching of musculoskeletal therapy, emphasis is typically placed on muscle disorders in the evaluation of functional loss of motion, thereby focusing rehabilitation efforts on muscular retraining and development. Mennell argued that because joint disorders are often the cause of secondary muscle changes, particularly atrophy and spasm, restoration of joint play should be considered an essential contributing factor leading to improved brain-body functioning and optimal performance.

Through his decades of collecting anecdotal research, Mennell developed the following four basic joint play concepts:

- Normal muscle function is dependent on normal joint movement and governed by the nervous system

- When a joint is not free to move, muscles intended to move the joint are not free to move it

- Muscles cannot be restored to normal tone if the joints they move are not free to move

- Impaired muscle function may create greater derangement of motion-restricted joints

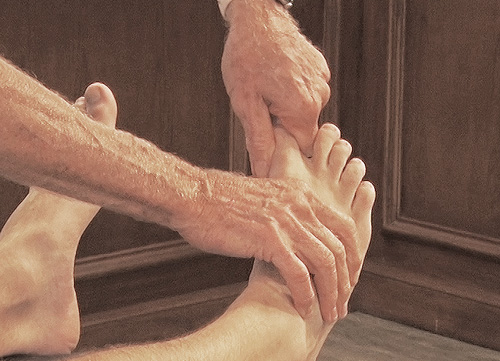

Mennell believed that abnormal reflexogenic cycles were a common clinical finding when dealing with musculoskeletal disorders, and that the prime fault often arose from loss of synovial joint play. Further he postulated that sensory input and motor output could be enhanced once this prime fault was corrected resulting in improved proprioception and a localized calming of central nervous system noise. In Images 3-4, I demonstrate a couple of basic joint play techniques that Mennell developed for addressing ankle and big toe restrictions.

Assessing Tibiotalar A-P Joint Play

- Client moves his body so ankles are off the end of therapy table

- Therapist begins assessing for anterior- posterior glide with right hand grasping and bracing the distal tibia bone while his left hand webs around the talus bone

- Therapist’s hands create a counterforce as he pushes posteriorly with his left hand while resisting with his right

- Next, the therapist reverses this move by pulling on the talus while resisting at the tibia

- Therapist compares side to side and records his findings on assessment sheet

Assessing Big Toe Joint Play

- Therapist’s left thumb and fingers grasp the big toe while therapist’s right hand braces the metatarsal bone

- Therapist flexes and extends client’s toe assessing for 90º of flexion and 45º of extension

- With hands in same position as above, therapist begins sidebending, rotating and translating the big toe (MTP joint) while resisting this motion by bracing the 1st metatarsal bone

- Therapist records finding of restrictions to joint play on assessment sheet

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.