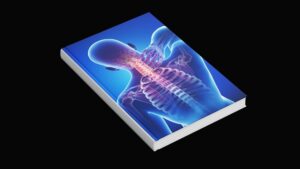

The coccyx, or tailbone, is a small but significant part of the spine. The name comes from the Greek word for “cuckoo,” since the bone resembles a cuckoo’s beak (Figure 1). Though often dismissed as unimportant, the coccyx serves as a structural anchor for key ligaments and muscles of the pelvic floor, and its misalignment or injury can cause surprising ripple effects throughout the body. Ida Rolf famously referred to the coccyx as the “seat of the soul,” a reminder that this little bone can influence not only biomechanics but also the way clients feel in their bodies.

Coccyx pain has been recognized for centuries, with the first documentation appearing in 1588. In 1859, the physician James Simpson coined the term coccydynia to describe pain arising from the coccyx. Today, we know that pain here often follows trauma, such as a fall, a blow during contact sports, or repetitive compression in activities like cycling, rowing, or prolonged computer work. These injuries can cause fractures, dislocations, or abnormal movement at the sacrococcygeal joint, setting off inflammation and degeneration of cartilage. Childbirth is another common cause, as the coccyx becomes more mobile during the final trimester to allow for pelvic expansion. This mobility, while necessary, can also stress muscles and ligaments, producing inflammation and sometimes leading to arthritis in the joint.

Unfortunately, clients who complain of tailbone pain often feel dismissed. Physicians sometimes minimize or belittle these symptoms, with coccyx pain even being referred to as the “lowest form of low back pain.” Yet those who experience it know that it is far from trivial. Coccydynia can make sitting, standing, and even simple daily tasks extremely painful and can reduce quality of life in profound ways.

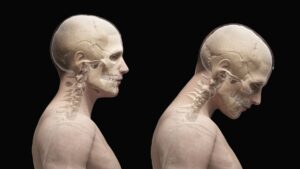

The coccyx is formed from three to five fused vertebrae at the very base of the spine. Functionally, it serves as a shock absorber when sitting, flexing slightly forward as weight is applied to complete the tripod of support formed by the coccyx and the two ischial tuberosities. When misalignment or injury interferes with this function, clients often adapt by leaning forward or to one side in order to shift weight away from the coccyx. This compensation may protect the tailbone, but it can increase stress elsewhere, leading to issues such as ischial bursitis, pelvic imbalance, or chronic lumbar strain.

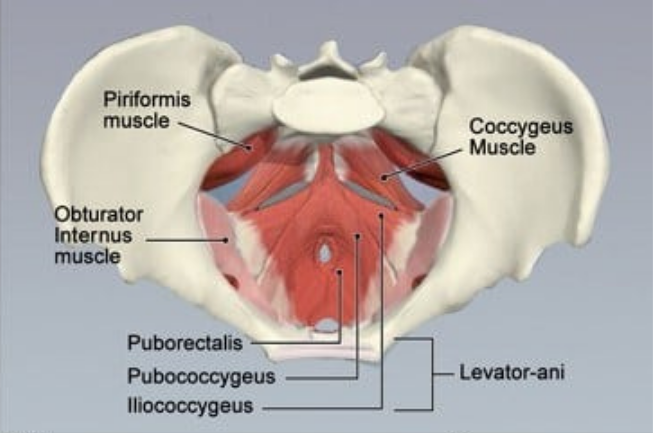

Several important muscles insert at or near the coccyx. On the anterior surface, the levator ani group — including the coccygeus, iliococcygeus, and pubococcygeus — attaches to provide pelvic floor support, maintain continence, and coordinate with the diaphragm for proper breathing (Figure 2). On the posterior surface, the coccyx anchors fibers of the gluteus maximus and connections from the biceps femoris through the sacrotuberous ligament. These muscular relationships make it clear that coccyx dysfunction can influence both pelvic stability and breathing patterns.

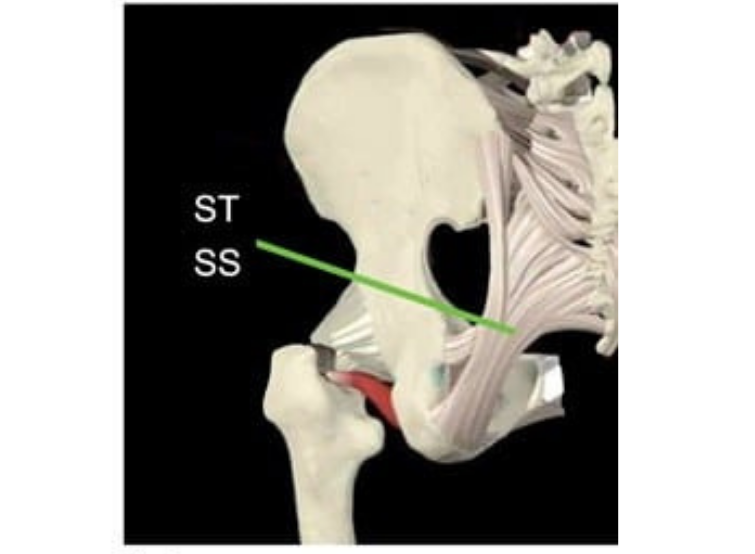

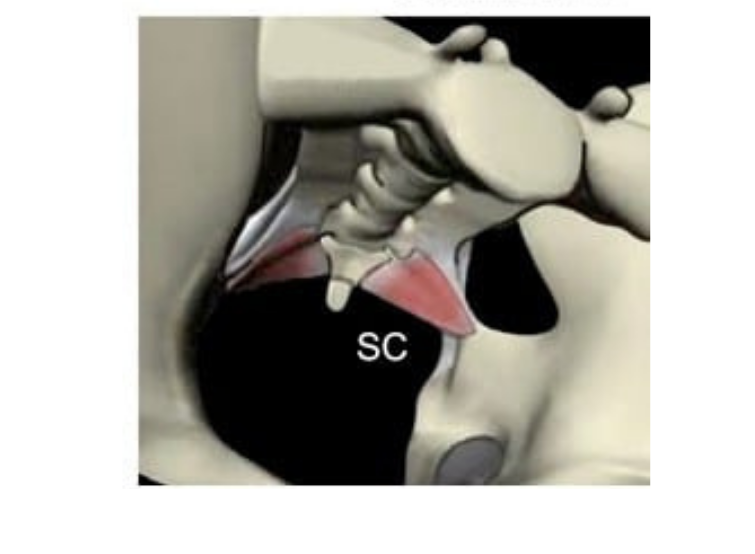

Ligaments also play a critical role. The sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, and sacrococcygeal ligaments connect the coccyx to surrounding structures and act as levers during motion. When the coccyx is hooked or pulled out of alignment, these ligaments can transmit strain throughout the pelvic bowl, creating pain and dysfunction (Figures 3 and 4).

Symptoms of coccydynia can vary but often include severe localized pain at the tailbone, bruising after trauma, pain with sitting or direct pressure, and discomfort when moving from sitting to standing. Some clients report pain with bowel movements, straining, or even sexual intercourse. Chronic cases may involve taut, fibrous bands in the pelvic floor muscles, especially the levator ani, sphincter ani, and coccygeus, which form in response to guarding and create further imbalance. Other muscles, including the obturator internus, gluteus maximus, and adductor magnus, may also become involved, contributing to pelvic pain and abnormal breathing mechanics.

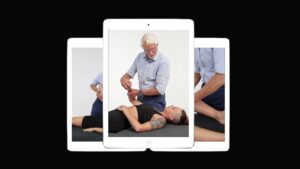

Massage and manual therapy can be highly effective in treating coccyx pain. The first goal is to restore balance to the pelvic bowl and lumbar spine by gently releasing overactive muscles. Once this balance is established, the therapist can use the ligaments themselves as levers to reposition the coccyx. In practice, this may involve palpating the coccyx, applying a gentle posterior pull on the ligaments, and holding for 10 to 60 seconds until the tissues begin to soften. A contract–relax approach can enhance results, with the client asked to gently contract the pelvic floor for a few seconds before relaxing, which allows the coccyx to move more freely (Figure 5).

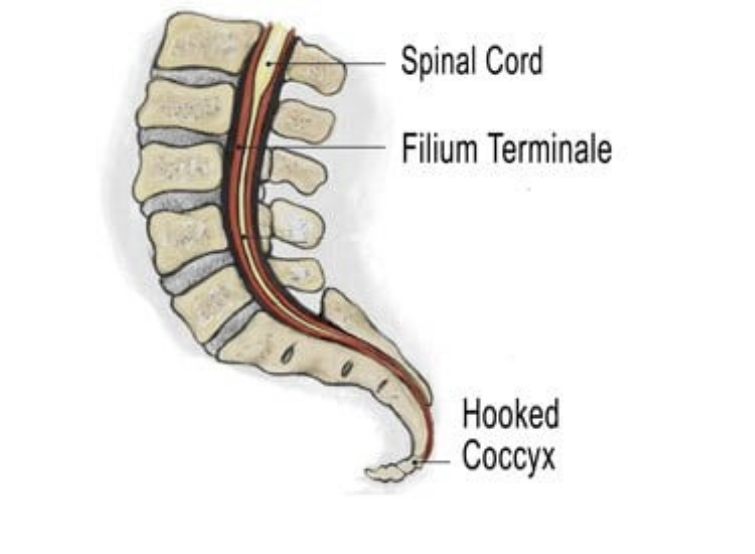

Because of the coccyx’s close relationship to the dural membrane through the filum terminale (a connective tissue strand anchoring the spinal cord) coccyx work can sometimes provoke strong emotional responses. As the sacrococcygeal ligaments pull the coccyx forward, they also stretch and compress this sensitive structure. Clients with long-standing coccyx misalignment may present with not only pelvic or low back pain, but also headaches, hip dysfunction, or widespread tension related to this dural pull. For this reason, therapists should always approach coccyx work with care, seek permission, and explain the techniques thoroughly before beginning.

Addressing coccyx dysfunction can bring surprising relief. Clients often discover improvements not just in sitting comfort, but also in breathing, pelvic floor function, and overall spinal balance. For massage therapists, remembering Ida Rolf’s insight about the coccyx as the “seat of the soul” provides both a practical reminder and a deeper metaphor. When this tiny structure is free and balanced, the entire body often feels more grounded and at ease.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Dalton Technique Tour course!

NEW! USB enhanced video format

Discover deep tissue, pin and stretch, nerve mobilization, and graded exposure stretches in this comprehensive “technique only” program. Upon completion, you will receive 16CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office. Save 25% this week only. Offer expires Monday, January 19th. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course.

BONUS: Order the home study version and get access to the eCourse for free!