The Masters Golf Tournament certainly proved to be an entertaining event this year as Tiger Woods did the unthinkable and pulled off his first Masters victory since 2005 (Fig. 1). It was the 43-year-old’s first major tournament win in more than a decade. Everyone who follows golf knows of his relentless work ethic and as I watched his final putt to win the Masters, it was – for me, one of the great moments in sports, particularly when you consider that he’s undergone four back surgeries since 2014, including an L5-S1 spinal fusion and a spinal stenosis procedure for severe sciatica. In an effort to understand why Tiger and many of our golf clients suffer low back pain, I dedicated a chapter in my “Dynamic Body” textbook. Here’s a “fly-by” on what I discovered.

Back Pain & the Crunch Factor

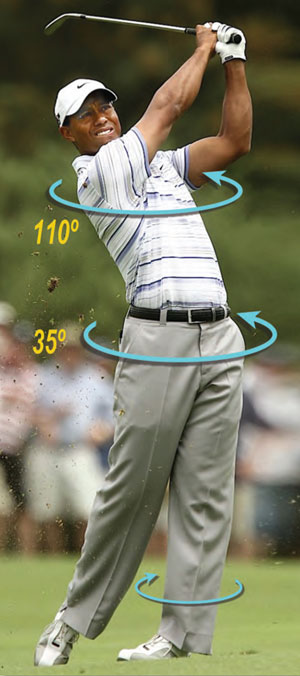

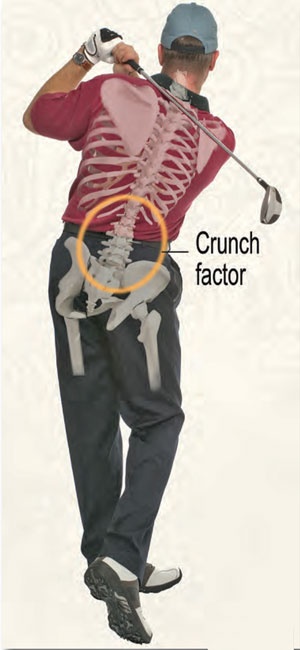

Researchers agree that back injuries are the bane of a golfer’s existence and are primarily related to improper swing mechanics and the repetitive nature of the game.1,2 Although it is considered low impact, the golf swing is one of the most dynamic motions in all of sports. The rotational forces placed on the back during the swing are equal to more than eight times one’s normal body weight and even when performed correctly, can place great strain on muscles, ligaments, joints, and neural structures. Yet in the right hands, the swing of a golf club can inspire awe especially in professional golfers like Tiger Woods, where highly coordinated sequencing of muscle activation allows for a fluid and reproducible movement. This split-second swinging maneuver requires such precision and uses so many muscles that it’s no wonder the golfer’s body is often a ticking time bomb for acute injuries. Because the golf swing is such a unique body movement that combines lumbar compression, shearing, torsion, and sidebending all in a split second of time, even in great golfers like Tiger, this “Crunch Factor” combo of high velocity rotatory forces coupled with trunk sidebending, often leads to debilitating back pain (Fig. 2).

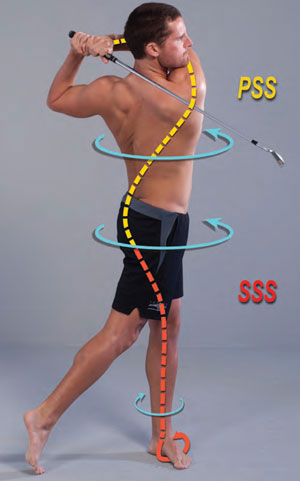

According to a 2007 study led by golf-injury expert Andrew McHardy, Ph.D., nearly 41º of golfing back injuries occur around impact or during early follow-through.3 At impact, 70 to 75º of body weight should have transferred from the non-target foot to the target side foot. The lower thoracic and lumbar spines now must sidebend to the right while rotating left. During the finish, the body continues to rotate toward the target. If the spine is maintained in a neutral position, the paravertebral tissues will experience less shear strain and less damage from rotational loading. At the conclusion of the swing, the spine should be erect, the pelvis and shoulders level and perpendicular to the target line, with most of the body weight distributed to the outside of the left foot (Fig 3). However, if the spine sidebends and extends excessively in the reverse “C” finish, the lumbar vertebrae will be subjected to compression during loaded rotation, i.e., the crunch factor.

Another study published in the Journal of Biomechanicsfound that golfers with low back pain from the crunch factor were overly dependent on erector spinae muscles for stabilization, rather than allowing load transfer to be distributed among more efficient core stabilizers, such as quadratus lumborum, transverse abdominis, multifidus, hip extensors, and thoracolumbar fascia.4 Ultimately, treating a golfer’s back pain is about perfecting the path for energy to travel through the body and into the ball. We must consider each point on the journey of this energy – from the hips through the coiled springs of the lower and upper body.

Summary:

Since the primary function of joints is to transmit stress when stabilized by muscle contraction, anything that disrupts this action prevents muscles and enveloping fascia from achieving maximum leverage to move the body through a desired action – such as a smooth golf swing. The greater control the golfer has over new and diverse movement patterns, the better he or she will perform, with decreased odds of injury.

With a revitalized and functionally balanced body, joints and muscles operate at optimal levels of motor recruitment and synchronization. As motor learning of this complex grooved maneuver improves, so does the golf swing and, in turn, one’s love for the sport!

References

1. Lindsay, D., & Horton, J. (2002). Comparison of spine motion in elite golfers with and without low back pain. J Sports Sci, 20(8), 599-605.

2. Vad, V.B., Bhat, A.L., Basrai, D., Gebeh, A., Aspergren, D.D., & Andrews, J.R. (2004). Low back pain in professional golfers: the role of associated hip and low back range-of-motion de cits. Am J Sports Med, 32(2), 494-497.

3. McHardy, A.J., Pollard, H.P., & Luo, K. (2007). Golf- related lower back injuries: an epidemiological survey. J Chiropr Med, 6(1), 20-26.

4. Cole, M.H., & Grimshaw, P.N. (2008). Trunk muscle onset and cessation in golfers with and without low back pain. J Biomech, 41(13), 2829-2833.

Learn how to identify and treat strain patterns before they become Pain patterns

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.