Techniques as demonstrated at Oklahoma City Workshop

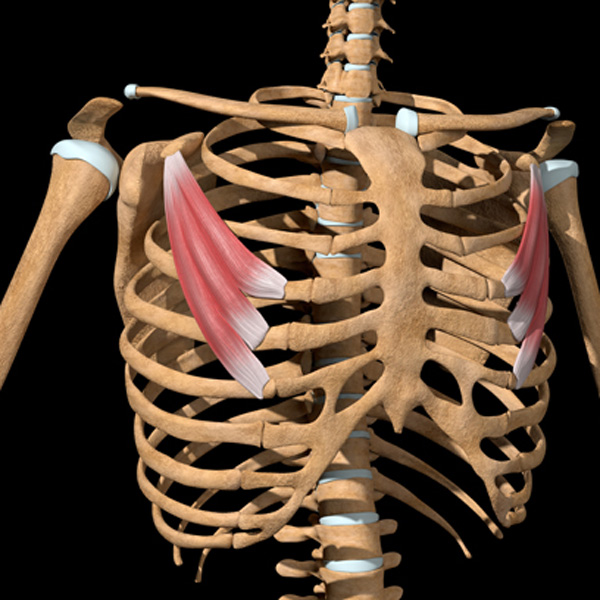

Pectoralis minor is a major player when it comes to bad posture, subacromial impingement and neurogenic thoracic outlet. Some believe that pectoral overactivity results from prolonged (flexion-addicted) sitting or working with arms out in front of the body. I tend to agree, but also feel that much of the chest wall tightness therapists palpate results from central nervous system (CNS) protective guarding and reflex spasm due to tension, nerve compression, altered joint neurology, and athletic overuse syndromes.

Nerve compression from joint alteration anywhere along the brachial plexus’ course may cause the brain to reflexively “splint” anterior chest wall tissues in an attempt to prevent further perceived neural insult. Accompanying dural membrane irritation can set the stage for pain-spasm-pain cycles or, in the early stages, the client may only experience symptoms such as shortness of breath, emotional distress, and restricted glenohumeral mobility …with no pain at all.

During the standing evaluation, pay particular attention to humeral positioning and scapular winging. A tight protectively guarded pec minor can reflexively inhibit serratus anterior causing the glenoid fossa to become more vertically aligned.1 This results in internal humeral head rotation and increased risk of rotator cuff impingement. Further, the protracted shoulder girdle causes increased activation of the levator scapula and upper trapezius in an effort to maintain glenohumeral stability. The typical end result is neck and t-spine stiffness seen in so many desk jockeys and overhead racket athletes.

Also assess using the “Floor Angel” position with client lying supine, humerus abducted and elbows flexed to 90 degrees (Image 1.). Ask the client to externally rotate his arms and slowly extend over his head. Tight pecs will not allow the client’s shoulders to lie flat against the therapy table during this maneuver, and they may experience anterior glenohumeral pain. To reduce the pain and relax the overactive chest wall musculature, I use Graded Exposure Stretching techniques. The goal is to try and get the client’s brain to associate slow, precise movements with security instead of pain.

The controlled manipulation of pectoral tissue combined with facilitated movement can provide safety from stretching too far. Using muscle energy and pin-and-twist maneuvers, the client is encouraged to gradually push the stretch discomfort barrier a bit further. By progressively introducing graded exposure stretch to areas that have been problematic in the past, the nervous system begins associating the new movement with safety instead of pain. Over a series of sessions, I’ve noticed a marked decrease in protective pectoral muscle guarding and an increase in pain tolerance during joint stretching maneuvers.

GOAL: Create brachial plexus space

LANDMARK: Chest Wall

ACTION: Bilateral elbow pec release

- Therapist’s elbows hook pec fascia and move tissue laterally to open up front line

- With client’s arms abducted to 135º, client begins externally and internally rotating both arms

Repeat 2-3 minutes and assess for improved shoulder rotation

ACTION:

- Therapist grasps client’s left wrist and begins internally and externally rotating client’s left arm

- Therapist’s forearm contacts the pec minor muscle at the coracoid process and resists external arm rotation

Repeat for 2 -3 minutes and reassess for improved soft tissue mobility

References

1. Kendall F, McCreary E, Provance P,Rodgers M,Romani W. Muscles:Testing and function with posture and pain. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.