The following is an excerpt written by Gil Hedley from chapter #5 of Erik Dalton’s book, Dynamic Body: Exploring Form Expanding Function, which features guest contributions from some of the leading thought leaders and practitioners in the massage profession. The rest of the chapter can be read in the Dynamic Body textbook, available as part of the Dynamic Lower Body home study course or as a standalone purchase.

Fascial Relationships

At every turn, I was asking these questions over and over: “Is that supposed to be there?” and “Is that stuck to that by accident, or is it normal for them to be like that?” An anatomy flash card describes an “origin” and an “insertion” for every “muscle” in the body. While one can differentiate from the whole a length of ensheathed muscle proteins spanning from the pubic bone to the tibia (famous “muscle” called “gracilis”), it was all the stuff I had to cut away to “make” that “muscle” that was catching my attention.

Did it belong there? Why didn’t anyone draw or otherwise document the 18 inches of filmy fascia – the filmy fascia that demonstrated better tensile strength than steel and was fixed along its length to the other “muscles”? (Answer: There’s not enough room on the flashcard!) Why did I find a three-inch long common “head” shared by the “semitendinosis muscle” and the “long head” of the “biceps femoris muscle”? I thought they were different structures with separable “origins.” Is their union typical, or an anomaly? (Answer: typical.)

The first time I would see something unexpected, I’d think, maybe that’s unusual, that’s not mentioned in the book. The second, third, and fourth time I’d see the same thing, I’d start suspecting either there’s a plague in this donor program, or perhaps it might belong there after all. The 50th time, I’m starting to be pretty sure that relationship belongs there. The 200th time, I can tell you with a fair degree of certainty it’s going to be there before I ever apply the scalpel. I’ll catch up with you the 1,000th time to let you know if I’m still pretty sure of that.

So, you can see this was, for me at least, a long, slow process, which amounted to starting from scratch with the cadavers and letting them teach me which tissue presentations are common and which are uncommon. The process involved dropping preconceptions, doctrines, and dogmas. I had to start with a clean slate to discover the “normal” ways that tissues transition from one texture to another, and to discover what the “suboptimal” relationships were – the relationships that arose from particular pathologies or from limits (of varying etiologies) upon movement.

Skin to Superficial Fascia

For a detailed visual introduction to the normal relationship of the tissues in the human form, I have created The Integral Anatomy Series. For the purposes of this chapter, though, I’ll jot out a few notes regarding what I’ve learned. For starters, the relationship of skin to superficial fascia is fibrous and fixed. In the elderly, the thinning skin may demonstrate a somewhat diminished fibrosity and basement structure on the back of the hands or feet, for instance. However, in the main, the skin is the skin of the “superficial fascia” (also known as the subcutaneous fat, the adipose, the pannicula, and so on.). Skin and superficial fascia consequently move together. Skin and superficial fascia consequently move together. When you “roll” skin, you are rolling skin and superficial fascia relative to the deep fascia.

Superficial Fascia to Deep Fascia

The relationship of superficial fascia to deep fascia is more variable. In some places, it is relatively “loose,” meaning there is plenty of “play” between them. You can “slide” superficial fascia in numerous areas of the body over the underlying deep fascia. In other areas, the relationship has less play than normally available. No matter what, the superficial fascia is “supposed” to be connected to the deep fascia, and it always is – the quality of this relationship is what I am always seeking to explore. That everything is one is the overarching reality. It is the nuances of the relationships that keep me coming back to the table.

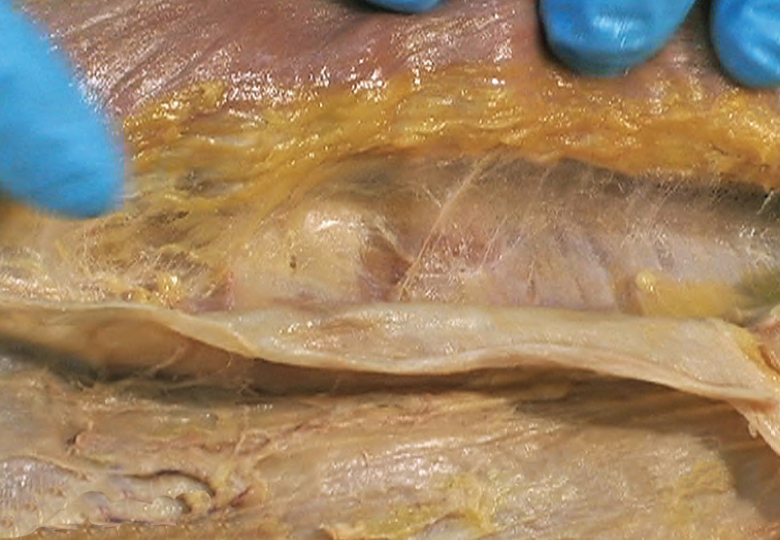

Where there is relatively more play between superficial and deep fascia, one commonly finds what I call a “filmy fascia.” This filmy fascia is a relatively loosely woven transition zone between the superficial and the deep fascia. Within this transition zone, the complement of adipose cells in the fascia is significantly diminishing, as the loose areolar superficial fascia transitions to the texture of the more fibrous and regularly oriented deep fascia.(Image 1.) If I pull the superficial fascia in tension up and away from the deep fascia, the matted filmy fascia intervening between them looks like cotton candy, which my finger easily disrupts or differentiates. That is not because the fascia is intrinsically weak, but rather because I have pulled its stranding apart in a manner atypical to its normal lie and configuration. It looks like fuzz. I have made it so.

At the 2007 Fascia Congress, a physiologist chastised the anatomists for using the term “loose fascia” to identify tissues that are, in fact, physiologically extremely strong. Anatomists tend to call things loose that they can poke their fingers through. Different strokes for different folks, but his point is well taken. Even steel cracks when sufficient shear forces are induced.

Deep Fascia to Muscle and Bone

The deep fascia is normally related to muscle tissue in a variety of ways. Sometimes, the muscle fibers anchor directly into the deep fascia. In other places, the deep fascia is only loosely related to the underlying muscle layer. Sometimes, we find filmy fascia as a transitional tissue between deep fascia and the epimysium of the muscle layer – much as we sometimes find this filmy fascia between the superficial fascia and the deep. (Image 2.) In some places, the deep fascia predictably dives straight down to the bone via large (famous) septa. (Latin lesson: one “septum,” two or more “septa.”) Sometimes, the septum detours on its way to bone by first investing more muscle tissue along the way. In other places, the deep fascia is diving within the “muscle” itself, in the form of innumerable small (not famous) septa.

Within the Muscle Layer

Within the muscle layer itself, we find numerous similarly textured, characteristically formed tissue groupings, to which names are conventionally assigned. The relationships along the length of these tissue groupings are of several varieties, including relationships via filmy and fibrous fasciae.

Filmy Fascia and Muscle Tissues

“Muscles” often relate to each other along their length through filmy fasciae, in a manner similar to the above described, more playful interfaces between superficial and deep fascia. When pulled apart, these fasciae look like fuzzy cotton candy. This cotton candy appearance is normal for ubiquitous filmy fasciae that have been lifted from their normal positions and placed in tension. This fuzzy look may be great in a picture, but it gives an illusory representation of the tissue, whose normal appearance in situ is not all that photogenic!

Fibrous Fascia and Muscle Tissues

“Muscles” not related via filmy fascia may be related to each other along their length, through numerous fibrous septa, which never made it into the books or flash cards. These septa are places of leverage for contractile muscle fibers, distinct from their termini (origins and insertions), and unlike the more filmy and playful kind of connection. (Image 3.) However, both kinds of fasciae are perfectly normal. I’m quite sure that, as a practitioner of structural integration, I spent more time than was kind to my clients attempting to “free” these normal relationships from their moorings in these unnamed normal septa. Please accept my apologies! I knew not what I did!

An Aside on Technique

While it is true that these tissues, whether connected by filmy or fibrous relationships, provide access into the whole, one’s goal should never be, in my opinion, to vivisect the client – no matter how fun it may be to “get in there” and “do what needs to be done.” Better to meet the tissues where they are, and allow the contact to highlight, and identify, the existing connection, whatever the state may be.

Muscle to Bone

The muscle, considered as a layer, forms a relationship to bone and visceral membranes. When dissecting, I often have the impression that the muscle is painted on the bone. I affectionately call the vastus intermedius “bone paint.” When looking at a classroom skeleton – which at great expense has been daubed with paint supposedly representing muscle origins and insertions – take that presentation with a big fat grain of salt. There should be a whole lot more paint! That having been said, the relationship of the muscle layer to bone is also often characterized by tendinous sheaths and fascial thickenings. These sheaths and thickenings occur where the investment of the muscle fibers becomes absent of visible muscle proteins, and where the investment then transitions, progressively or abruptly, into the periosteum at a bony prominence.

Muscle to Visceral Membranes

The muscle layer, invested in its deep fascia, also provides an external anchor, to which the parietal membranes of the viscera normally adhere. The muscle wall adheres to the visceral wall – parietal means “wall” – and this, too, is normal. The intercostal muscle tissue, along with the ribs, and the abdominal musculature – which, in its inner layer is perfectly continuous with the respiratory diaphragm (see volume three of my series) – provide the normal anchorage for the outer membranes of the visceral spaces.

Membranes to Membranes

In contrast to all these normal filmy, fibrous, and adhesive relationships described in the preceding paragraphs, when we get down to the viscera themselves, we encounter sliding surfaces of a whole other order. Viscera are not connected via the playful, filmy fasciae that intervene between the superficial and deep fascia. Instead, the viscera slide by one another, like pigs in a poke, or kittens in a sack. Small amounts of serous fluid, as opposed to filmy fasciae, mediate the contact. The organs themselves have “skins,” also known as visceral serous membranes. These are fully and normally adherent to the organ tissue structure – indeed, they are part and parcel of it. These membranous surfaces, the visceral peritoneum, the visceral pleura, and the visceral pericardium, truly slide relative to the parietal layers respectively, as well as relative to the visceral layers of the other organs. (Image 4.)

So the parietal layer is adherent to the muscular and bony perimeter of the visceral space, and the visceral layer is adherent to the tissues of the organs themselves, but the visceral and the parietal layers should move freely, relative to each other, as should the visceral surfaces themselves, relative to one another. Freely, that is, within the range of motion delimited by the normal and, generally, somewhat predictable ligamentous relations of the organs themselves.

About the author

Gil Hedley has been offering his Six Day Intensive Hands-On Human Dissection Workshops since 1994. In addition to authoring several books and many articles, Gil is also the producer of The Integral Anatomy Series, four feature length DVD volumes documenting his unique layer-by-layer whole-body approach to the human form through on-camera laboratory dissections. Gil can be reached for course schedules and contact information through his website. www.gilhedley.com

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.