The following is an excerpt written by Erik Dalton from chapter #8 of his book, Dynamic Body: Exploring Form Expanding Function, which features guest contributions from some of the leading thought leaders and practitioners in the massage profession. The rest of the chapter can be read in the Dynamic Body textbook, available as a standalone purchase or as part of the Dynamic Lower Body home study course, eCourse.

The Biomechanics of Walking in Heels

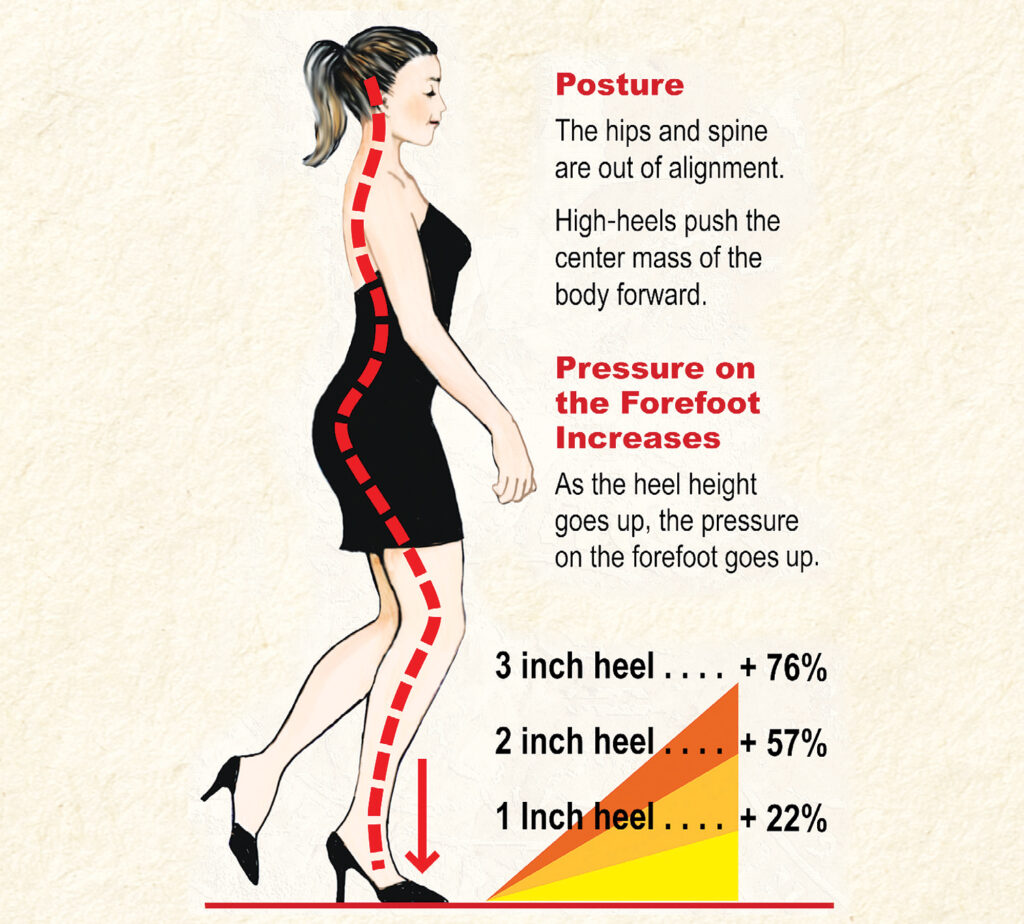

The term researchers use to describe the slope, or slant, of the heel, from rear to front, is the “heel wedge angle.” A higher heel means a greater angle. Biomechanically, when wearing a low-heeled shoe, the heel assumes about 40 percent of one’s body weight, and the ball takes on the other 60 percent. Amazingly, the simple act of switching to a high-heeled shoe drastically changes the distribution of body weight. In high heels, the ball of the foot bears about 90 percent of one’s body weight, whereas the heel assumes a meager 10 percent.

As the trained eye observes the posturo-movement mechanics of ball-walking, it is easy to see how shifts in foot and ankle weight mess up the sequence of normal barefoot walking, which goes heel, to ball, to toe, to push off. Once the heels are elevated three or more inches, they carry very little weight, forcing the ball of the foot to bear the bulk of the burden during the push-off phase of walking (Image 1.).

Some mammals – dogs, cats, raccoons – are designed to walk and run on the balls of their feet. Ungulates, such as horses and deer, actually run and walk on their tiptoes. In fact, few mammalian species other than bears, humans, and great apes land heel first. However, a heel-first gait is more economical. Not only does it provide a stable platform and better proprioception, but it also promotes longer strides, which means less energy gets lost to the ground.

In the Journal of Experimental Biology, Dr. David Carrier, a professor of biology at the University of Utah, states: “We consume more energy when walking on the balls of the feet or the toes than when walking heel first. Compared with heel-first walkers, those stepping first on the balls of their feet used 53 percent more energy, and those stepping toes-first expended 83 percent more energy.”2 Maybe that’s how some high-heeled gals stay so slender.

The energy-sapping act of ball-walking has developed into quite a fad as fashion designers continue to jack up heel heights. One would think that with the advent of nine-inch stilettos, these designers may have eliminated the need for an anatomic heel altogether. In fact, the inevitable finally happened in 2009, when famed shoe designer Manolo Blahnik premiered the first “heel-less” shoe, shown in Image 2.

Functionally, these ball-walking hybrid shoes decrease shock absorption during gait, and the loss of ground reaction force increases stress on the feet, legs, and spine. Compared with walking heel-first, both heel-less shoes and stilettos dramatically decrease leverage and mechanical advantage.

Stilettos: Aerobics on Stilts

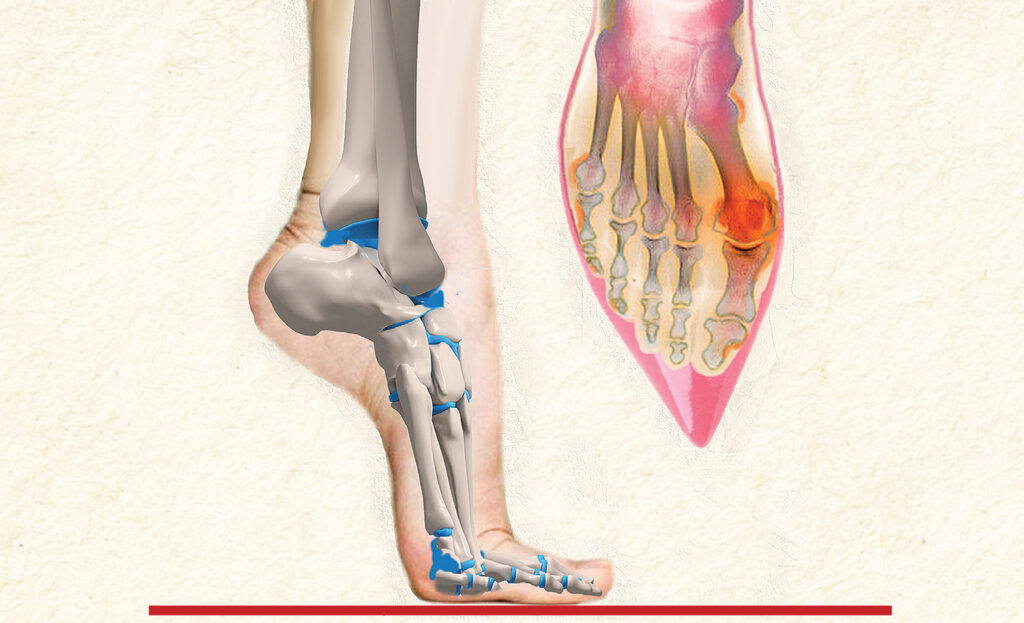

One-quarter of the bones in the human body are housed in the feet, along with 33 joints and more than 100 muscles. If toes are crammed into a stiletto and unable to spread, it is impossible for them to be in the correct anatomical position. Eventually, global and core foot muscles forget how to “turn on” and “shut off” in the correct sequence, and no longer activate properly during gait. Moving around on stilettos all day is especially taxing on the central nervous system. As if the brain didn’t have enough to do, this unbalanced walking forces it to rethink and remap millions of deeply engrained motor control patterns.

Sooner or later, this leads to:

- Altered firing order patterns

- Muscle imbalances

- Abnormal motor recruitment

- Synergistic muscle dominance

- Musculo-fascial splinting

In its early stages, the transition to unbalanced heel-wearing may be stressful and could lead to clumsy injuries. Given time, however, the brain – through a process called neuroplasticity -reluctantly adapts to the abnormal movement postures and relearns them as “normal.” In fact, some heel-toting ladies tell me they feel awkward and unstable when they kick off their heels and go barefoot.

Fixing Fashion’s Dysfunction

How does one fix the foibles of fashion? We must educate our clients about the pitfalls of high-heels, offer home retraining exercises, and discourage this harmful fashion habit. If common sense fails, the next question is whether we should accommodate such self-destructive behavior by developing a treatment plan, even though we know it may be useless in the long run.

Apparently, some think that we should accommodate those who refuse to give up fashion. I recently saw a TV interview with female Hollywood actors touting a new exercise program for women who wear stilettos. They were singing the praises of an upscale gym in Los Angeles, called Crunch, which now offers 45-minute “Stiletto Strength” classes. These classes are designed to restore muscle balance to the legs and calves of women who wear high-heels. It may not be a bad idea if the program included whole-body reconditioning to treat the compensations.

Certain manual and functional movement methods may provide temporary relief from the distress symptoms associated with wearing high-heels, but these modest gains will not be effective when it comes to re-establishing natural gait. Again and again, research shows that natural gait is biomechanically impossible for any shoe-wearing person, even those who stick to flatter soles. 1,2

Until the client agrees to reduce the number of hours she spends in high-heels, stubborn musculo-fascial imbalance patterns will persist. The elevated heel of the shoe will continue to shorten and tighten the Achilles tendon and calf muscles, causing tentacles of strain to infiltrate all systems of the body – from plantar fasciitis, shin splints, and bunions, to knee, hip, and low back pain.

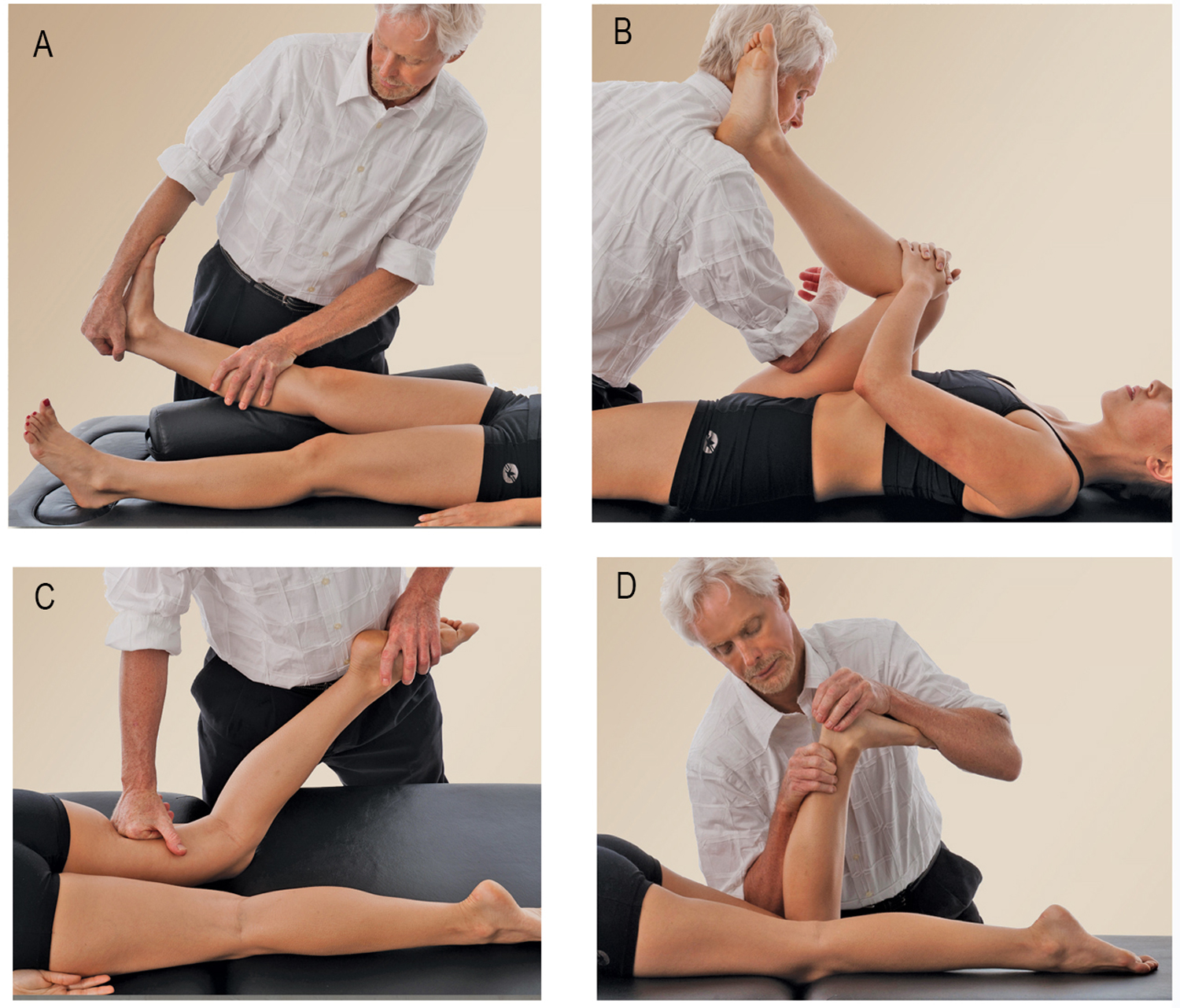

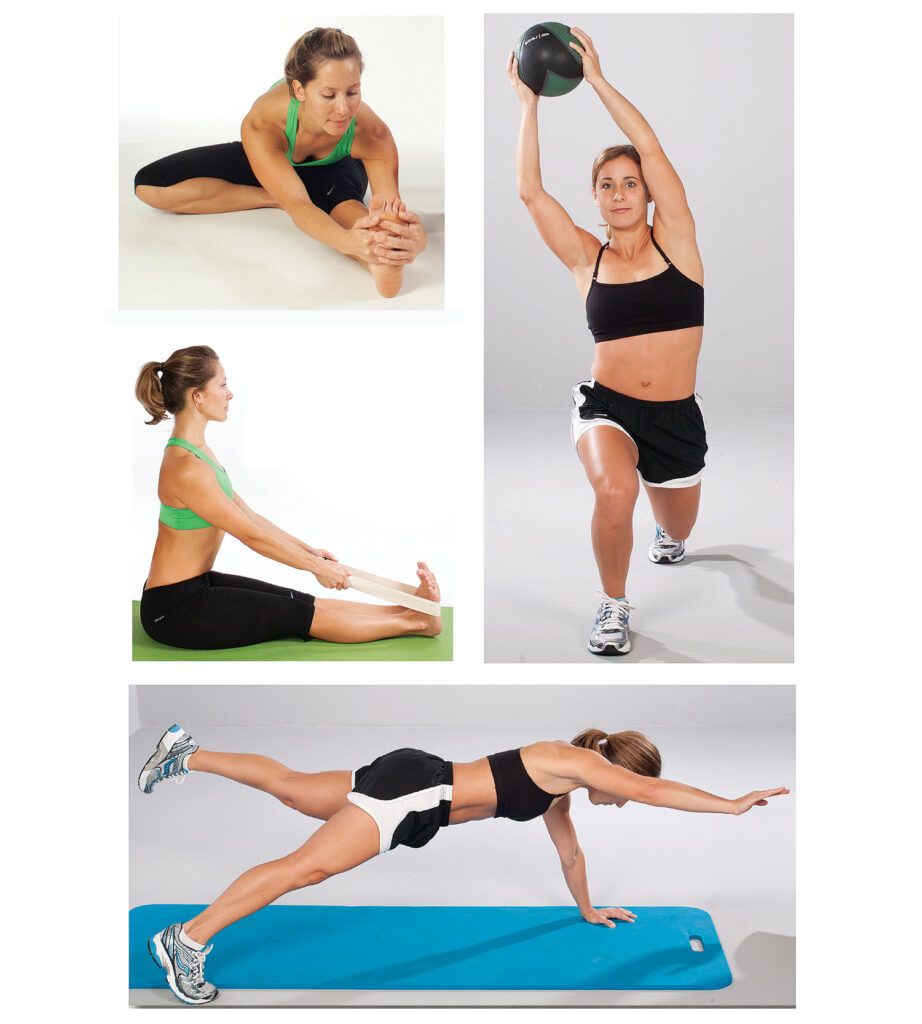

Stretching, strengthening, joint mobilization, structural integration, and functional movement training are all effective tools for re-establishing proprioception and motor control, as well as relieving pain from damage – but only if the client is willing to forsake her high-heel habit. A few of my favorite joint-stretching and Myoskeletal Alignment routines for mobilizing foot fixations and the accompanying fascial compartmental syndromes are pictured in Box A. Along with these routines are functional movement home retraining exercises to re-establish length-strength in low back, hip, and leg balance and improve motor control (Box B). Add these to your touch-therapy repertoire, along with appropriate gait analysis and whole-body biomechanical assessments.

Box A: Myoskeletal Alignment Techniques

A. Mobilize ankle with Figure-8 maneuver

B. Hamstring Release

C. Separate biceps femoris from IT-Band

D. Retinaculum release

Box B: Home Retraining Exercises

Propulsive Power Thief

Many women love to wear high-heels – and many men like the way women look when they wear them. It is true, however, that some people suffer for vanity. Women should be cautious about wearing high-heels constantly, or for long periods of time. Clearly, the human foot was not designed to walk in stilettos – or cowboy boots, for that matter. The foot is specifically constructed to land in a heel-to-toe rolling motion, in which the arch, ankle, and knee absorb shock, or stored energy, and release the ground reaction force up the kinetic chain to counter-rotate the torso and pelvis.

As we saw in our barefoot wall-standing demonstrations, the heeled shoe steals this propulsive power from tendons, ligaments, and leg muscles. Heels place the foot and leg under greater stress to achieve the demands of propulsion (Image 3.), and the borrowed power must be leeched from structures higher up the kinetic chain, including the knees, thigh muscles, hips, and trunk. As a small army of anatomical reinforcements is recruited to rescue the handicapped fascial tissues, the body continues losing energy to the ground.

Heels of any height set in motion a series of gait-negative consequences, making natural gait meaning the barefoot form – impossible. Don’t let your clients be slaves to fashion – fix their feet, and restore the spring in their step.

References

- Lee, C.M., et al. (2001). Biomechanical effects of wearing high-heeled shoes. Int J Ind Ergon, 28(6), 321 – 326.

- Carrier, D.R., Cunningham, C.B., Schilling, N., & Anders, C. (2010). The influence of foot posture on the cost of transport in humans. J Exp Biol, 213, 790 – 797.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.