In a study of one NFL team from 1998-2007, the occurrence of hamstring pulls accounted for 85 injuries, second only to knee sprains, which came in first at 120 injuries1. Hamstring injuries often plague competitive and weekend warrior athletes for years, giving the illusion that the initial injury never healed. But recurring problems are commonly due to re-injury rather than a single isolated episode. When a disorganized web of scarred collagen tissue creates a chemically toxic environment at or around the ischial tuberosity, blood, nutrients, and neurology are disturbed. Connective tissue that replaces normal healthy collagen is weaker than normal muscle tissue and more susceptible to the risk of re-injury with even less intense activity. Statistics show that re-injury to the hamstrings occur in about one-third of athletes, most commonly within the first two weeks upon return to play2. This places extreme importance upon evaluation of the severity of the injury and the resultant manual and movement rehabilitation program to ensure that the athlete is strong enough to return to competition without the threat of re-injury. Hamstring rehab can take anywhere from 2-6 weeks or longer depending on severity and therapeutic delivery methods used.

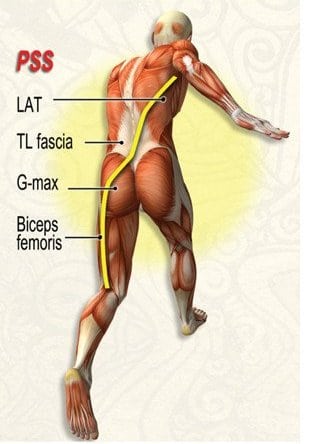

Obviously, the role of the hamstrings is important because of their unique ability to stabilize the pelvis in the transverse and sagittal planes during trunk flexion and rotation, i.e., three-dimensionally. Anatomically, the hammies are capable of producing both internal and external rotation as well as hip extension. The balance of musculature across the hip in all three planes is critical to successful functioning during all sports and work activities. Disruption of normal force coupling in either the sagittal or transverse plane will have tremendous effects across the lumbar spine, pelvis, and lower extremities. Image 1. shows fascial force coupling between the biceps femoris, sacrotuberous ligament, glute max, thoracolumbar fascia and contralateral latissimus dorsi. Weakness in any of the Posterior Spring System (PSS) structures causes the biceps femoris to overwork and lends it to injury.

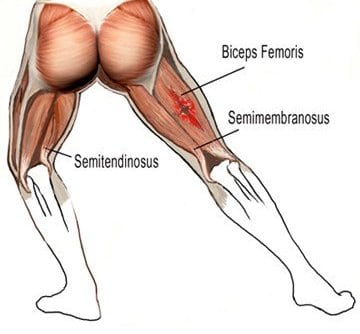

Typically, when a biceps femoris is injured during running, one end of the muscle is trying to shorten while the other end of the myofascial unit is lengthening; the muscle is in effect trying to stabilize at one end and produce substantial force at the other. Adding to the problem is the dual (tibial and fibular) innervation at the proximal bifurcated heads. If one branch fires late, the uneven pulling can place unbearable stress on its partner. In the absence of proper flexibility, the incidence of injury increases (Image 2. ). Initially, the emphasis of treatment is on restoring and keeping the range of motion. However, too much stretching and movement can result in more dense scar formation, limiting the muscles’ healing ability. When an athlete is told to move the leg only in pain-free motions, the brain begins to re-map a new neurological motor pattern and compensations develop. The injured player consciously or unconsciously alters movement patterns to avoid re-stressing the damaged connective tissue.

Stretching & deep tissue… good?

It may seem during this last stage that the hamstrings simply will not loosen up. Modalities such as NMT, structural integration, orthopedic massage, active isolated stretching, myoskeletal alignment and functional movement training are often used to help restore length-strength balance in the musculo-fascial kinetic chain. Once all the neurological components of the hamstring injury have been addressed, the therapist may need to pump some juice into the cross-linked scar tissue allowing the collagen to heal faster and function better.

Functional training goals during this period may include improving running coordination of the trunk and pelvis (neuromuscular control), sport-specific activities such as quick starts and stops, and improving strength. Exercises will continue to be used from the previous phases, but their intensity and focus on quality of movement is increased. Some movements that have been shown to help strengthen and reduce re-injury include high-knee marching, quick running drills, forward-falling running drills, explosive start drills, and eccentric muscle actions (muscle is lengthened while it is activated).

More research is needed to better assess the causes of hamstring injuries, i.e., muscle imbalances, neurological weakness, SI joint inhibition and myo-kinetic kinks. More and better strategies are needed to prevent occurrence and reduce prevalence. No matter the sport or the method of delivery, this injury is one that causes a multitude of problems and time away from competition. More knowledge on prevention and rehabilitation of hamstring injuries is a focus of many pain management, orthopedic massage and sports medicine practitioners.

References

- Heiderscheit B, et al. Hamstring Strain Injuries: Recommendations for Diagnosis, Rehabilitation and Injury Prevention. J Orthop Sports Phys Therapy. 2010 February; 40(2):67-81

- Hammer, Warren. Functional Soft-Tissue Examination and Treatment by Manual Methods. Sudbury.

Save 25% off the "Pain Detectives In Ireland"

eCourse

Join us as we put on our detective hats to uncover the source of our client’s pain complaints using the osteopathic ART method (asymmetry, restriction of motion, and tissue texture abnormality) on four cases: Judy, Sharon, Scott, and Diane. Learn how to apply ART techniques to boost your ability to solve your own client pain puzzles and become your own Pain Detective to solve the mystery of your clients' pain complaints. Pain is a crime. Let’s solve it! Save 25% this week only...until midnight Mon February 23rd!

Get Lifetime Access: As in all our eLearning, there is no expiry date to completing the course. You get easy access to the program online and work at your own pace.