Sacrificing complexity of movement for stability

Working in a technologically driven society has caused an explosive and expensive increase in work-related costs, with injuries occurring to categories of workers previously considered low risk for anything more serious than the occasional paper-cut.

Often seen as a structurally subtle body segment, the neck is burdened with the tedious task of supporting the human head. With tension and microtrauma from desk-occupied postures commonplace in today’s workplace, is it really any surprise that head-on-neck and neck-on-thorax disorders serve as some of the most common complaints that drive people into our bodywork practices?

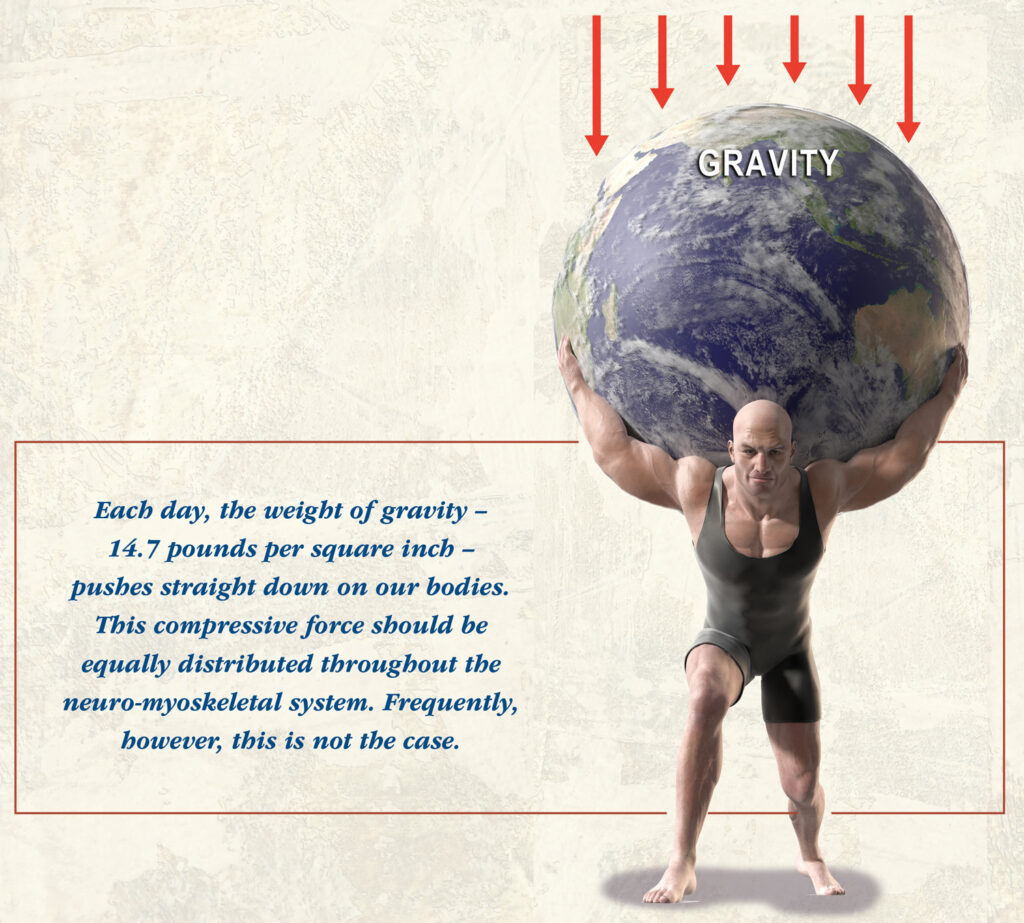

The battle against gravity

Muscles are designed to glide freely around joints and across neighboring connective tissues as the motor cortex, cerebellum and brain stem beautifully orchestrate a complex array of highly specified movements. When observing professional gymnasts at work, one immediately recognizes the astonishing quality, variety and complexity of their coordinated movement patterns. Conversely, the elderly foot-shuffler appears to have body areas frozen in time. Sadly, years of tension, trauma and poor posture—combined with gravitational exposure—force the human body to sacrifice “complexity of movement for stability.”

Today, more than ever, people are inclined to sit for hours in isometrically contracted postures without adequate physical activity. When muscles contract, fuel is burned and waste products accumulate. In time, these chemical irritants may alter the muscles’ resting length. Prolonged sitting leads to slumping, as people spend countless hours tied to work terminals, home computers, school desks and television sets. As the heavy head slowly drops forward and down, the scapulae externally rotate and protract, increasing thoracic kyphosis and flattening of lumbar lordosis.

Exhausted from battling gravity, sustained isometric hypercontraction in intrinsic cervical extensor muscles such as semispinalis, longissimus, suboccipitals and multifidus become oxygen starved. While extrinsic (phasic) muscles such as trapezius, rhomboids, posterior rotator cuff prefer burning glucose for fuel; the deep intrinsic support muscles thrive on oxygen. When tension, trauma and faulty posture reduce the amount of O2 delivered to intrinsic postural muscles, fatigue sets in, causing the gravitational load to shift to the extrinsics.

Extrinsic muscles are dynamic and designed to provide quick bursts of energy. Since phasics contain a greater number of fast-twitch fibers, they do not respond well to sustained compressional loading and quickly give out and the energy-depleted intrinsic muscles are once again made to bear the load. This decompensation cycle marks the beginning of a domino effect that structurally/functionally manifests as: reduced flexibility; loss of range of motion; and an unattractive, forward-head, slumped-shouldered posture.

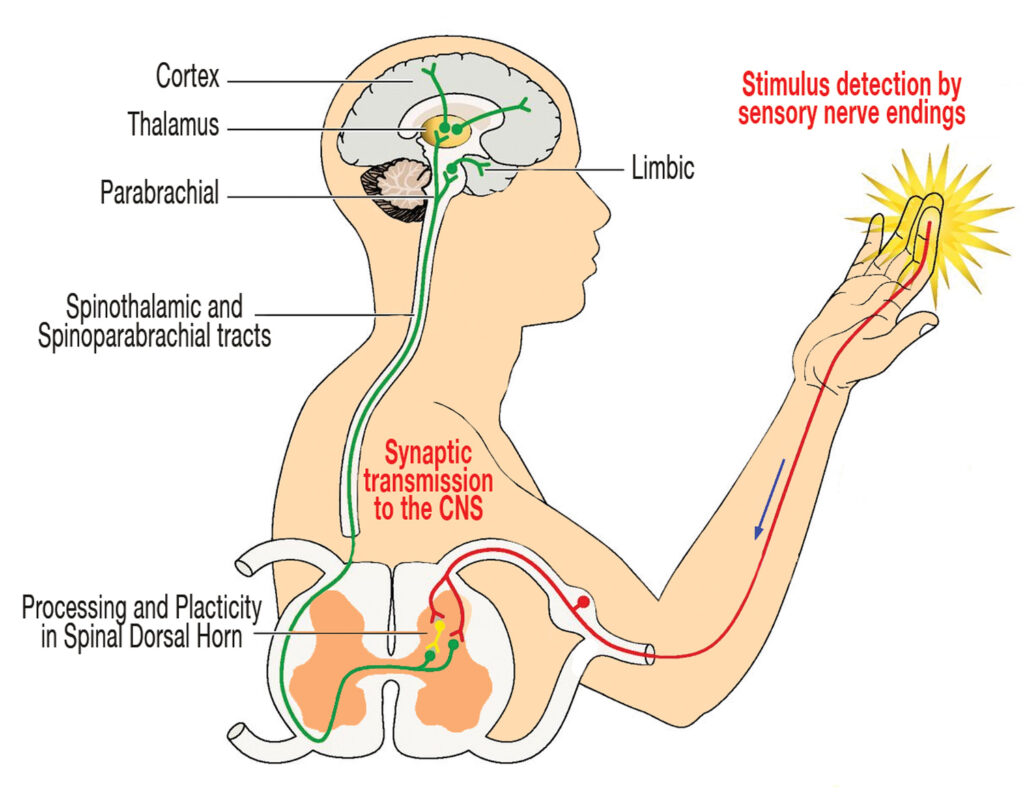

The human body’s bony framework and supporting soft tissues are densely populated with proprioceptive and danger-sensing sensory receptors that serve as the frontline of awareness. Faulty posture, micro- and macro-trauma, gravitational stress and resultant inflammation cause a breakdown of the smooth self-regulating function of these receptors. Soon the person begins to experience painful spasmodic episodes, as caustic waste products such as histamines, bradykinins and potassium ions collect in the neurologically tightened, nutrient-depleted muscle bellies. Prolonged toxic buildup stimulates sensitive chemoreceptors that flood the spinal cord and brain with noxious messages setting off an increased neurologic inflammatory response and more nociceptor stimulation.

Sustained isometric muscle contraction not only excites inflammation-sensitive chemoreceptors, but also specialized mechanoreceptors designed to monitor excessive stretching or compression of joint capsules, ligaments, discs, fascia and spinal rotator muscles. As chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors bombard the spinal cord with perpetual streams of noxious stimuli, the cord finds itself unable to handle the increased sensory input and quickly recruits danger-signaling nociceptors. These tiny non-myelinated receptors can fast-track sensory messages to the thalamus and the brain stem’s reticular formations, warning of the possibility of actual tissue damage. Depending on the type and amount of peripheral input and the health of the cortical processing system, the brain may decide to layer the area with protective spasm to prevent further insult or may decide to take a ‘watch and wait’ stance… or possibly decide it’s time to bring the problem to awareness by eliciting a pain response.

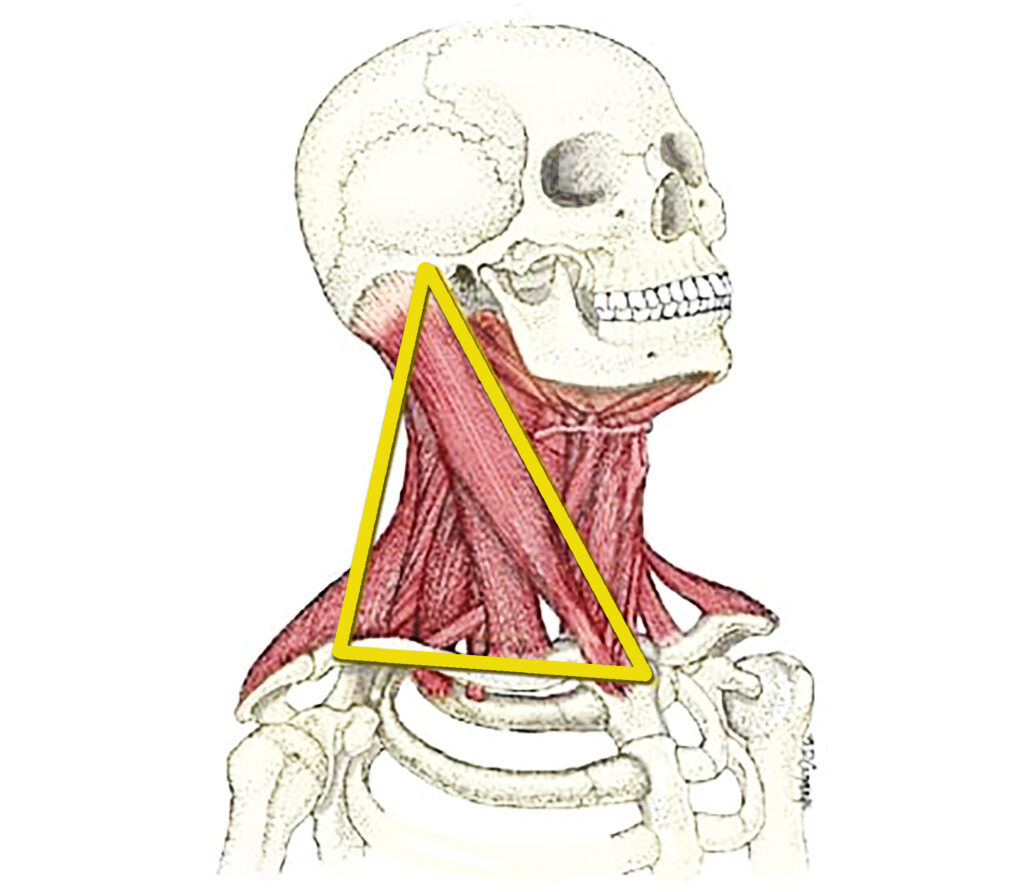

Interestingly, excessive cortical stimulation causes recruitment of specific sets of muscles “hard-wired” to fire in a predetermined order to guard the vulnerable area. Unfortunately, the first muscles enlisted are often the very same tissues responsible for creating the head-forward posture to begin with; namely, the sternocleidomastoids (SCMs), suboccipitals and anterior scalenes. As these highly innervated soft tissues tighten and shorten, the head and neck are drawn even farther forward resulting in increased myospasm and protective guarding. The brain quickly calls up the next battalion of troops to help counter this intolerable forward-head drag.

One can easily visualize why the brain might recruit the broad splenius capitis muscle to anchor the neck posteriorly due to the shared (front and back) attachments with the SCMs at the mastoid. With this arrangement, the splenius capitis offers a perfect counterforce to the powerful anterior pull of the SCMs.

The levator scapulae are also high on the recruitment list due to their common front/back attachments with the anterior scalenes at C1-C4 transverse processes. This design offers perfect resistance from the constant drag of typically hypertonic anterior scalenes. When working properly, the antigravity function of this four-muscle, dual-tent system is ideal in allowing the human head to gracefully balance on the neck. However, when structural integrity fails due to traumatic changes, the neck’s intricately designed antigravity springing system loses out to compressive gravitational forces acting on it. As cervical curve diminishes, the weight burden falls to deep spinal tissues such as apophyseal joints and intervertebral discs… the devastating beginning of what the medical profession loosely calls degenerative disc disease.

Although most researchers today dismiss the nerve root as a pain-generating structure due to the lack of positive, objective signs (such as paresthesias, sensory deficits and motor loss), its importance in the pain-management picture cannot be completely overlooked. Loss of disc height combined with vertebral foramina bone spurring can eventually deform and tether the nerve root. As the dural sheath and surrounding capillary beds undergo prolonged mechanical deformation, ischemia, intraneural edema, and loss of axoplasmatic flow of vital nutrients break down axons. Some biomedical researchers estimate that 10-15 percent of clients presenting with this type of chronic neck pain suffer from what has been termed the “silent nerve compression syndrome.”

It is tempting for therapists to immediately resort to chasing the pain rather than developing sensible strategies to effectively deal with the client’s problem. Both client and therapist often settle for any immediate symptom alleviation. Yet a strongly holistic approach that includes brain-based and functional movement exercises helps bring the body back into balance offers more satisfying long-term outcomes that ultimately help prevent future recurrences of acute pain and leads to more productive living.

Poor posture may start as a ‘tissue issue’ due to tension, trauma or overuse injuries, yet it eventually manifests as a sign of functional weakness in the brain’s hardware. This weakness may stem from faulty peripheral input, inaccurate cortical processing, and/or flawed output. Just remember that your brain sets the tone for all your muscles. Like an overprotective mother it decides how much activation to allow and it always errs on the side of caution. The brain can activate or inhibit muscle tone and balance depending on what it determines to be the safest course for you. We are wired for survival. Your (Mom) brain is there to protect you and when functioning properly, knows when too much or too little of a good thing is right for you.

For more information go to the Treating Trapped Nerves course.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.