Image 1. See how the amazing tennis star Serena Williams’ right arm has adapted to being right hand dominant

The SAID principle (Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands) is a classic sports medicine term that describes how physical adaptations develop when the body is placed under stress, thereby allowing the body to better handle future stressors. A common example is seen in this image of famed tennis star Serena Williams (Image 1). It’s easy to visualize how the muscles, ligaments, and bones of Serena’s right arm have thickened in response to excessive demands from her years of engaging in a right motor dominant sport. Simply put, the body gets better at doing whatever it does regularly.

So, how does the SAID principle apply to the suboptimal postural patterns we see in our practices? Bottom line: Sitting for hours in a flexion-dominant posture or performing exercises using poor form or less than perfect posture will cause the client’s body to get better at adopting poor form and less than perfect posture. This is “postural plasticity” at work.

Poor posture may start as a “tissue issue” due to tension, trauma, or overuse injuries. Eventually, however, it manifests as a sign of functional weakness in the brain’s hardware. This weakness may stem from faulty peripheral input, inaccurate cortical processing, flawed output, or a combination of these factors. Although there are seven primary brain areas responsible for the neurology governing posture, in this newsletter, I’d like to focus on two: one that promotes forward head postures and another that permits these postures.

Pontomedullary Reticular Formation (PMRF)

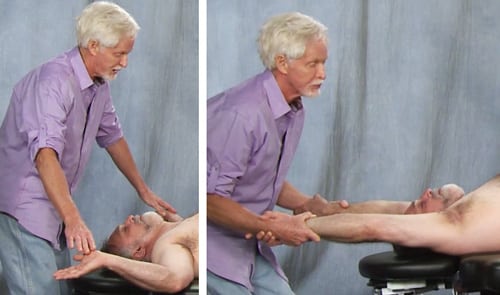

The PMRF is a dynamic sorting and switching station located in the brainstem at the pontomedullary junction, where pons meets the medulla (Image 2). It is considered the epicenter for postural control and “the powerhouse of posture,” according to the American Postural Institute. The PMRF houses eight cranial nerves that carry out vital motor and sensory functions, including eye-ear coordination to enhance head righting reflexes and balanced gait.

When functioning properly, the PMRF inhibits cervicothoracic flexion, which, in turn, effectively resists gravitational exposure. Clients with PMRF disorders commonly present with an upper cross syndrome pattern — forward jutted chin, internally rotated arms, protracted shoulder girdle, and thoracic spine hyperkyphosis.In this population, the PMRF is unable to neurologically resist slumping, which causes connective tissue and joint adaptations in the myoskeletal framework.

It’s best to assess for PMRF weakness with the client unaware you’re evaluating them. To accomplish this, I begin observing my client’s posture as they enter the office, looking for front-to-back and side-to-side and rotational strain patterns that may indicate PMRF weakness. During the intake evaluation, I’m silently asking the client to prove to me that he or she does not have an upper cross, right motor dominant, or cross-patterned gait problem. Weeding out these common compensatory patterns in early sessions gives me a good starting point for my bodywork intervention and also provides clues to possible PMRF weakness side-to-side.

For example, the client in Image 3 is asked to perform a modified table angel test, and I see that some of his upper cross pattern is coming from bilateral PMRF weakness. To help activate the pons and medulla, I apply a couple of graded exposure torso extension stretches (Image 4). For those with unilateral PMRF problems, or rotational crossing patterns, I always check for vestibular imbalance side-to-side. Let’s look at an example of this dysfunctional pattern.

As sensory integration takes place through good bodywork and corrective proprioceptive exercise, the brain stem transmits impulses to the muscles that control posture, balance and movement. Of course, there are multiple neurological systems that contribute to optimal posture so our therapeutic goal is synergistic integration of these system. As we begin to normalize and restore flexor/extensor synergy and postural stabilization during dynamic movement, our clients stand tall and move better.

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.